A collective impact learning lab

Learning on the fly has been at the heart of the Burnie Works collective impact initiative.

- Burnie Works community-wide collaboration is applying the collective impact framework to address low school retention and high youth unemployment.

- The initiative demonstrates that collective impact requires getting comfortable with emergence – developing strategy through doing and learning.

- This place-based initiative has discovered that participationg and doing in collaboration is what brings alignment with the goal.

Burnie Works is a community-wide collaborative initiative in North West Tasmania that is applying the collective impact framework to address the complex problem of low school retention and high youth unemployment. Their generous learning spirit allows us to critically review how Burnie Works has interpreted and applied the collective impact framework and examine what is working well and what could work better.

… collective impact is all about getting comfortable with emergence…

Australia, like many countries, has been tantalised by the promise of the collective impact framework. Our hope is that the framework will transform the messy and time-consuming work of collaboration into significant and enduring impact for communities. Attracted by this, many communities and funders have begun the process of adopting a collective impact approach. They are learning that the promise of collective impact lies far beyond its deceptively simple and accessible elements and phases.

As Burnie Works shows collective impact is all about getting comfortable with emergence – with developing strategy through learning. Sound a bit new age and abstract? In the beginning I thought so too. But this article will unpack what emergence means in practice and in doing so make the promise of collective impact more real.

What is collective impact?

Collective impact is a framework to tackle complex problems – problems characterised by layers of stakeholders, with different perspectives and disagreements about the causes of the problem and the best solutions. These challenges require working across organisational boundaries, as they are beyond the capacity of any one organisation or sector to solve. To make progress, change is required across the whole system – known as systems change. All those with a stake in the problem need to work together to develop new approaches and solutions. This is why collaboration is the most appropriate response to complex problems.

The collective impact framework helps make collaboration work across government, business, philanthropy, non-profit organisations and citizens to achieve significant and lasting social change.

The authors of the framework, John Kania and Mark Kramer distinguish collective impact from other ways of working together: “Collaboration is nothing new. The social sector is filled with examples of partnerships, networks, and other types of joint efforts. But collective impact initiatives are distinctly different. Unlike most collaborations, collective impact initiatives involve a centralised infrastructure, a dedicated staff, and a structured process that leads to a common agenda, shared measurement, continuous communication, and mutually reinforcing activities among all participants.”[1]

The framework is comprised of five interdependent elements as shown in Figure 1.[2]

What is Burnie Works?

Burnie is a beautiful deep-water port town of 20,000 people, historically prosperous through manufacturing heavy machinery and shipping mineral, forest and agricultural resources to the world. Upheavals in mining, manufacturing and forestry; climate change and the global financial crisis – forces beyond the control of the community – resulted in major corporations closing their operations over a couple of decades of decline. By 2011, Burnie had one of the lowest rates of post-year 10 retention and highest rates of youth unemployment in Australia.

In 2010 the local community came together and developed the Making Burnie 2030 Community Plan. Through engagement and consultation facilitated by the local council, the community identified the key challenges to its preferred future: education, youth employment and socio-economic inclusion were seen as critical factors in helping the entire community become prosperous and healthy.

The [collective impact] framework gave shape and a narrative to what Burnie was doing.

The original mechanism that introduced collaboration to the leaders in Burnie was a Federal Government initiative with a place-based approach called Better Futures, Local Solutions (BFLS), however funding was withdrawn following the 2013 Federal election.

During this time the Burnie community had become aware of the collective impact framework and, like many collaborations, felt it had been written about them – or, at least, what they were aspiring to become. They recognised many of the elements of this framework were already present in both Making Burnie 2030 and the BFLS initiative. As one Burnie business leader said: ‘it was a moment of enlightenment’. The framework gave shape and a narrative to what Burnie was doing.

As a result, BFLS was reframed in 2014. A new governance group – the Local Enabling Group – was formed within the collective impact framework and under a common agenda called ‘Burnie Works’.

In March 2015, Burnie Works was recognised by The Search as Australia’s most promising early stage collective impact initiative, winning financial and in-kind resources to assist Burnie to strengthen its collective impact effort.

How does Burnie Works work?

As an early stage collective impact initiative, the focus of the work is to develop a common agenda with the community. Doing this with a diverse range of stakeholders takes time and requires a process. Typically, the core elements of creating a common agenda are to:

- Strengthen and deepen the community aspiration for change

- Build a shared understanding of the challenge

- Build your collaborative principles and capabilities

- Create a shared approach to achieving large scale change.

… they convened them [stakeholders] in small projects that sought to create immediate, measureable outcomes…

Many, if not most, collective impact initiatives start the process by focusing more on points 2 and 4 above. They build a shared understanding of the challenge by collecting baseline data, mapping the service system and capturing community perspectives. Some initiatives then work these inputs through regular meetings of cross-sector leaders and community engagement processes. Others bring these inputs into large convenings of 70-150 people designed to accelerate learning, engagement and the development of the common agenda.

Burnie Works did not tread this path; they focused on points 1 and 3. The priorities and direction articulated in Making Burnie 2030 provided a starting point through a collective focus and a shared sense of energy. The work was to harness that. Instead of engaging stakeholders in detailed agenda setting, they convened them in small projects that sought to create immediate, measureable outcomes for children and young people through collaboration. Since 2014 Burnie Works has convened six such projects. Here two are unpacked.

10 families

Design: The Burnie Works backbone team convened 20 government and non-government service providers to work collaboratively with 10 families whose children were experiencing difficulty staying connected to education. Families volunteered and worked with a key contact or service to identify and achieve their goals.

The purpose was two fold:

- That all children within the 10 families attend school at above average rates.

- That the participating services build the conditions and systems for collaborating to achieve that outcome.

Reflecting the purpose, the impact was also two-fold:

- After 18 months, all children from within seven of the 10 families were attending school at above average rates. For many families the support they needed to achieve their stated goals was complex, requiring many agencies to play a role over a sustained period of time. For one family, a parent was supported to undergo significant dental surgery to become less reliant on her school-aged children for in-home support.

- The participating services built the conditions and systems required to collectively achieve that outcome. Tangibly, they:

- Learnt how to share data and information

- Developed the agreements needed to support collaborative practice (MOUs, data sharing protocols, etc)

- Learnt what responsive and flexible service delivery meant in practice.

Less tangibly, they worked through:

- The mindset shift from ‘isolated’ impact to ‘collective’ impact

- Sharing power, decision-making and credit

- What it meant to work together closely when organisations have differing values, philosophies and models

- How to deal with the ‘loss’ inherent in collaboration, for example loss of control or attribution.

Dialling up what works: Through 10 Families Burnie Works learnt that stronger, more sustainable school engagement outcomes were achieved with younger children. They re-oriented the project, renaming it to ‘Everyday Counts’, and are currently scaling to work with 50 families with primary school aged children.

Dream Big

Design: Working with three primary schools and a large number of businesses, Dream Big sought to connect all year 5 students to their most desired workplace for the day. Students were awarded certificates and souvenirs from their visit. Also, business and community leaders were invited into the schools to speak about their personal journeys from school into their chosen careers.

The purpose was three fold:

- To lift the career aspirations of primary school students so they value education enough to remain engaged in education up to or beyond year 10

- To ‘change the conversation around the dinner table’, especially in families who, for many reasons, have been unable to participate in a work environment and where conversations and references to the world of work are not commonplace

- To connect the education and business sectors to elevate the importance of education in the community.

Impact: While insufficient time has elapsed to know whether Dream Big is impacting on year 10 retention rates, the activity-based data shows that schools, children and businesses are strongly engaging with the project. Children share stories about having the importance of education brought to life and their horizons broadened in terms of career options.

The impact regarding the connection between education and the community is more readily observable. As Rodney Greene, Burnie Works backbone leader, describes it: “Through Dream Big, education is now owned by the whole community, as evidenced by the involvement of so many businesses, and the administrative support of a school program by external agencies.

“One school principal had a light bulb moment when he realised 50 of his students were involved in a significant program that he had not had to worry about organising.”

Dialing up what works: Based on the learnings, anecdotal data and level of engagement, Dream Big has been expanded to seven primary schools, involving over 150 Grade 5 students and more than 80 businesses.

What can we learn from Burnie Works?

Burnie Works is an ever-changing example of collaboration and the use of emergence as a way to set strategy to address a complex challenge.

“This captures the risk and chaos but also the excitement and achievement as a new thing is formed…”

In complexity theory, emergence is defined as ‘coherent structures [that] coalesce through interactions among the diverse entities of a system’.[3] In Burnie this means learning what works by experimenting – learning by doing. They learn by facilitating small ‘experiments’, watching them closely for intended and unintended consequences, adjusting as they go and dialling up what works.

For Greene, the best way to describe emergence as a way to set strategy is ‘building a plane in the air’. “This captures the risk and chaos but also the excitement and achievement as a new thing is formed to achieve a preferred future.”

This is a very different approach to the current way we conceive of place-based reform – which is usually about integrating services or introducing a set of interventions that worked elsewhere. It is also fundamentally different from the way strategy is traditionally delivered, where the intended impact is determined and interventions selected which are then delivered consistently and unchangingly over time.

So what has it taken for many actors in Burnie’s system to get comfortable with emergence? It has taken a lot of letting go. Of many things.

“We have discovered that innovation within complex systems often uncovers issues, challenges and opportunities that would never have been identified through a detached analysis or a standard theory of change,” says Greene. “The reality is ‘we don’t know what we don’t know’.”

“… the most significant challenge for a number of services was to move beyond thinking of their own organisation…”

His words reflect the ability for social change leaders to let go of being the expert – of believing that their role in the system is to know the answers. Greene and his team have worked extensively, but gently, with leaders – one by one – helping them shift from isolated impact (ego leadership) to collective impact (ecosystem leadership). This work is time-consuming and inherently personal.

“Early on, the most significant challenge for a number of services was to move beyond thinking of their own organisation (their profile, service models, philosophy) to work together as a collaboration,” says Greene. “In a competitive environment where NGOs are seeking to differentiate and raise their profiles to gain funding support, this is a critical and challenging issue.”

… using emergence to develop strategies is effective. It is also measurable.

Commenting on the kind of relationships that collective impact requires, Greene says: “They need to be deep enough to create the trust to transcend (or replace) legal and contractual arrangements as these can never deal with every potential challenge and possibility arising from emergent solutions.”

The work of emergence has technical dimensions also. Easily the biggest one is how to share data. Greene says that in 10 Families, “we have had to develop processes for sharing information across up to 20 organisations where no contractual relationships existed.”

Above all, what we can learn from Burnie Works is that using emergence to develop strategies is effective. It is also measurable. The experiments of 10 Families and Dream Big (and others) create observable and measureable changes in the way people work together – higher levels of trust, alignment of leaders to the vision of Burnie Works, greater power sharing, information flowing more freely, resources being better targeted to needs. etc. These changes in dynamics and behaviour are the drivers of the systems change Burnie is seeking to make.

[© Regina Hill and Jenny Riley, 2016]

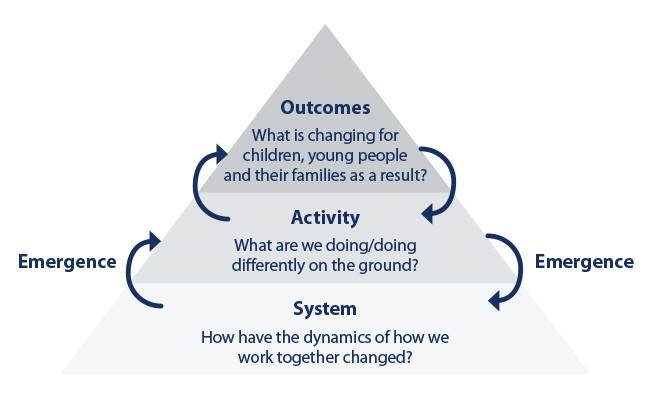

As shown in Figure 2, changed behaviours in the system level result in changed activities. Through 10 Families, existing activities like family support service delivery are more coordinated, flexible, responsive and effective. Through Dream Big, new activities are being scaled that link children to businesses.

There are other experiments too. It is the accumulation and scaling of these aligned activities that create the desired population level change Burnie Works is seeking – more children engaging with school, higher levels of year 10 and 12 retention and better transitions into employment or further training.

What’s next for Burnie Works?

In the scheme of things, Burnie Works is young. It is three years into a long-term change process where population level improvements typically take a minimum of seven years to be seen.

Since 2014 Burnie Works has been building the capacity of leaders and organisations to collaborate and develop strategies for change through emergence. At times untidy and uncertain, this approach has been very successful for them.

Making Burnie 2030 has provided the overarching vision and direction; and ‘experiments’ such as 10 Families and Dream Big have provided focus and impact on agreed priorities such as school attendance, school retention, aspiration and youth employment. Vision and emergence have worked together to create significant alignment of leaders and collaboration across sectors.

“… it is in participating and doing that brings true alignment.”

To reach population level impact Burnie Works recognise that their next phase is to develop the structures and rigour needed for scaled and sustained collaborative action. From a structural perspective, they have spent the last 12 months incorporating their backbone entity, strengthening their collaborative governance and investing in communication infrastructure. From a rigour perspective, they are building their capacity and relationships to develop the population and program level goals and indicators to which they will hold themselves and others accountable.

Burnie Works embarks upon this next phase of development with strong foundations in place. Their strength comes from the community’s level of engagement in, and ownership of, the initiative.

As Greene says, “We have been able to draw the entire community around a common agenda of valuing education and creating employment opportunities for our young people, and then mobilising individuals and organisations across sectors to contribute to this change.

“What is important here is that engagement is not achieved through a sterile policy environment, or a 20-point strategic plan or well articulated theory of change. While all these are important, it is in participating and doing that brings true alignment.”

As a result, collective impact is beyond a promise – it is the way change gets done in Burnie.

Author: Kerry Graham

Contributors: Nick Elliott and Rodney Greene

About Kerry Graham

Kerry is Director of Collaboration for Impact, Australia’s leading organisation for learning how to respond to complexity through effective collaboration. She has worked in social change for over 20 years holding executive roles within national non-profit organisations and advised governments on social policy. Kerry curates learning for and provides advice to communities, corporations, governments and non-profit organisations on collaboration and innovation in social change. Kerry is also a lecturer on collaborative practice with Centre for Social Impact at University of New South Wales.

About Rodney Greene

Rodney is Director of Community and Economic Development at Burnie City Council, a position he has held for nine years. This role allows him to focus on supporting the local community to develop innovative, long-term approaches to complex social and economic issues; at both a program and systems level.

SVA supported Burnie Works’ Local Enabling Group to develop its initial strategy to respond to its situation then and enable it to work in an evolving environment.

[1] Kania, J and Kramer, M, Collective Impact, Standford Social Innovation Review 2011

[2] FSG, Collective Impact (2011)

[3] Peggy Holman, Cultivating leadership in complex times