A framework for making difficult decisions

A prioritisation matrix can help you look at options in different ways – even with limited information.

- A prioritisation matrix is a visual tool that helps to rank, or choose, issues or activities to focus on.

- It can be particularly useful in the social sector, where many organisations have ambitious missions but constrained resources, and where data is limited.

- Matrices can be used where there are difficult choices, multi-variants, or when only qualitative information is available, as well as to accommodate numerous perspectives and priorities.

Management is about making decisions; the most obvious being ‘what do we do next’. However, sometimes, there is no clear path. In the social purpose sector these decisions are made harder by the lack of data and the number of stakeholders that need to be considered. While organisations can often identify options, they get stuck deciding which one(s) to choose.

Prioritisation matrices provide a framework to help address, and rank, complex options. As a result, they can help organisations make decisions and justify them.

What is a prioritisation matrix?

A prioritisation matrix is a visual tool to help decide which ‘things’ – be they issues, tasks, goals, etc. – to choose. It can be used in various situations where there are difficult choices, multi-variants, or when only qualitative information is available. Being a visual tool, it assists in looking at the problem in a new way and brings new perspectives to the table.

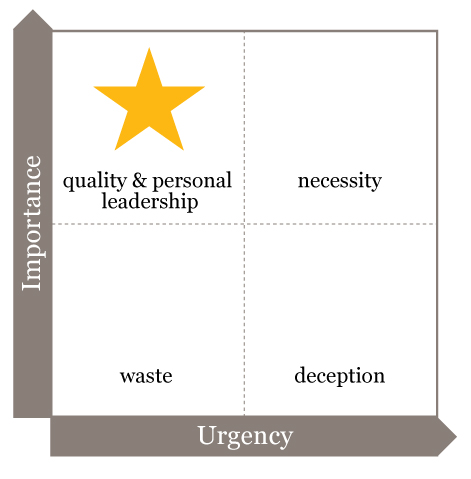

A simple example of a prioritisation matrix was one made popular by Stephen Covey in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. See Figure 1.

Covey uses ‘importance’ and ‘urgency’ to rank personal tasks, arguing that those who make time for important but not urgent activities are the most effective people.

– Tasks of high importance and low urgency fall into the ‘quadrant of quality & personal leadership’ and should be focused on.

– Tasks that are of high importance and high urgency fall into the ‘quadrant of necessity’ and should be managed.

– Low importance and high urgency tasks fall into the ‘quadrant of deception’ and should be avoided.

– Low importance and low urgency tasks fall into the ‘quadrant of waste’ and should also be avoided.

When would you use it?

The prioritisation matrix is of great benefit in making decisions – when it is used in the right circumstances. It is most useful in three circumstances: when narrowing down the number of activities, deciding what to measure, or sorting between risks.

1. Narrowing down the number of activities

The most common of these circumstances is narrowing down a number of possible activities. This generally arises as one of the following scenarios:

a) There are no bad ideas, but limited resources

This scenario occurs when an organisation has many viable options, but a lack of resources to address all of them.

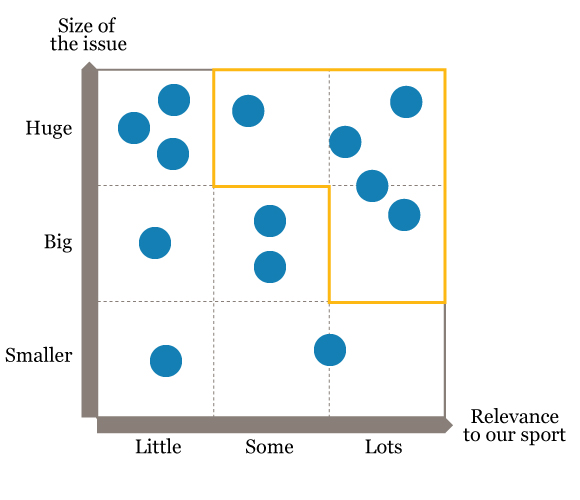

For example, a sporting organisation wanted to address two or three social issues. Due to its size, the organisation could have had an impact on any issue it chose. As all the social issues it identified were worth addressing, there were many viable options. So this scenario lent itself perfectly to a prioritisation matrix.

The organisation used ‘size of the issue’ and ‘relevance to our sport’ to rank the social issues. As it was looking at issues on a national scale, the organisation had access to data such as economic cost, number of people affected and amount being invested in the issue. Having this data meant the size of the issue was easier to determine. The relevance to the sport was based on the organisation’s judgement. For example, it judged that physical health is more relevant to the sport than homelessness.

Only issues that fell into the boxes outlined in red – the ‘sweet spot’ – were considered. See Figure 2.

A prioritisation matrix is not only about choosing what falls into the top right-hand box. The ‘sweet spot’, or where you draw the line on what is in and what is out, can be anywhere; it depends on the available resources.

b) There is a paucity of quantitative data

This scenario arises when there are many options, but a lack of data to know which are best. A lack of data leads to a high level of subjectivity and therefore difficulty making the decision.

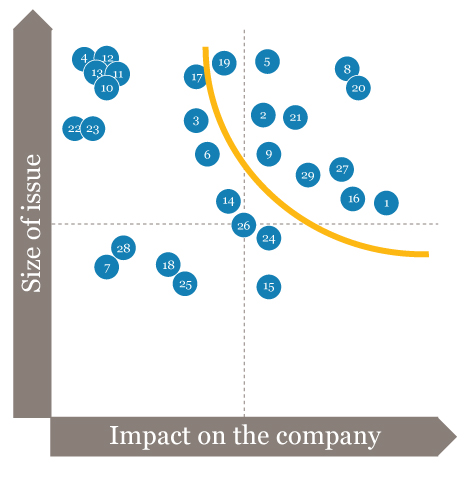

For example, an extractives company wanted to address one local social issue. This company had little localised data to draw on compared with the sporting organisation which had national statistics for each option.

Consequently, the prioritisation matrix used the organisation’s knowledge and anecdotal evidence to guide its thinking. In this instance, the criteria used were ‘size of the issue’ and ‘impact on the company’. The team chose the criteria, ‘impact on the company’, as they considered it smarter to invest in an issue that would also have a positive impact on the company and ensure longevity of the program). For instance, investing in employment programs may result in greater access to qualified staff.

In this instance a line was drawn, with everything above it landing in the ‘sweet spot’ (see Figure 3). As a result, the company identified the top 11 social issues in the local area and then grouped these together into themes such as education, environment and economy. This gave the company greater clarity on what area it should focus its investment in.

c) There are a variety of agendas

The most difficult scenario for a manager can be when there are opposing perspectives on what to do. The prioritisation matrix can help to navigate through this.

For example, a state orchestra had 40 goals in its strategic plan as a result of many people wanting to do many things. It was running into financial problems and could not possibly have achieved, or even attempted to achieve, all the goals.

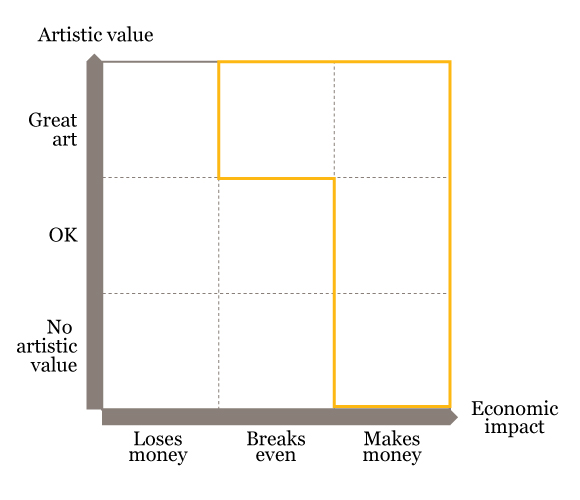

The board was assisted to prioritise all the 40 goals against the criteria of ‘artistic value’ (‘great art’, ‘OK’, and ‘no artistic value’ – the latter meaning that it didn’t push the orchestra’s artistic vision forward), and economic impact (‘makes money’, ‘breaks even’, ‘loses money’). In advance, the board agreed that only four of the nine segments were acceptable. See Figure 4.

In fact, of the 40 goals only four could realistically be placed in the desired part of the matrix. This led to a productive brainstorm of what the orchestra could do to both push its artistic mission, and address its financial challenges. As a result, the plan had to be rewritten.

2. Deciding what to measure

An integral part of any measurement project is deciding what outcomes matter most: what is material and worth measuring. Organisations can use prioritisation matrices when undertaking measurement and evaluation projects, and Social Return on Investment (SROI) projects.

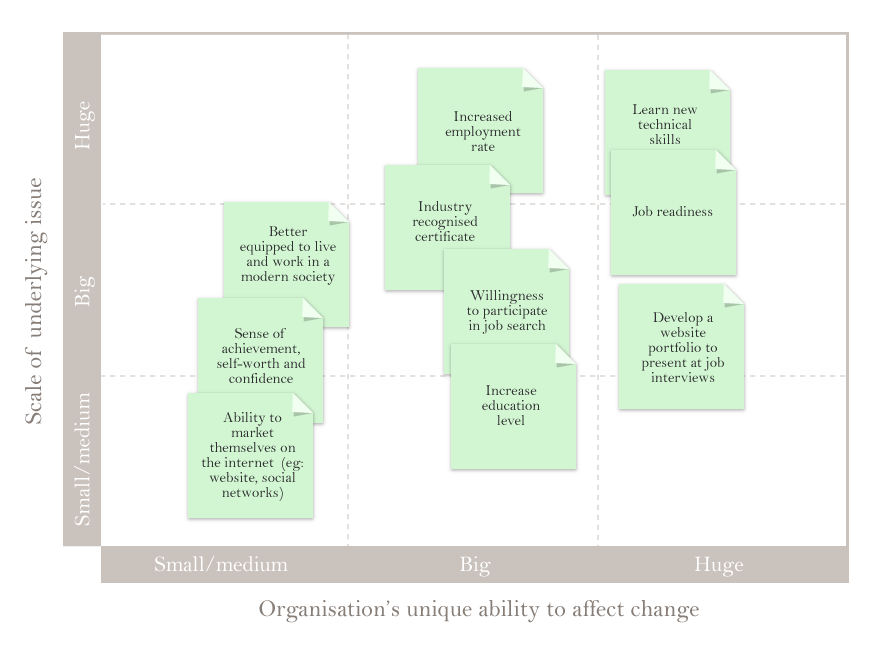

An example of prioritising outcomes can be seen in the Finding the golden thread article. In this case, a ‘Youth Transition to Work Program’ is used to demonstrate how outcomes are prioritised. See Figure 5.

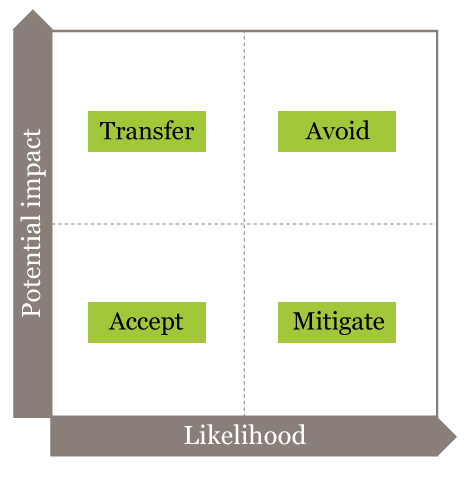

3. Sorting between risks

Risk assessment is part of any good strategic plan. Assessing risk, however, can be extremely complex. As such, a prioritisation matrix is often only one component of an overall risk assessment. Nevertheless, by using the criteria: ‘potential impact’ and ‘likelihood’, a prioritisation matrix can be a simple way of assessing risk. See Figure 6.

- A risk that would have a high impact and has a high likelihood of happening can be categorised as ‘avoid’

- One that would have a low impact and has a high likelihood of happening can be categorised as ‘mitigate’

- Those that would have a high impact and a low likelihood of happening can be categorised as ‘transfer’

- While those that would have a low impact and a low likelihood of happening can be categorised as ‘accept’.

How would you use it?

1. Decide on the process for applying the tool

A prioritisation matrix is most useful when you are able to get input from multiple stakeholders. A workshop environment is the best way to achieve this.

- The workshop should have the right people in attendance. This is not necessarily the most senior people. The selection is based on the role the person can play and what they bring to the table:

- Information: Can they provide information on an option?

- Responsibility: Are they in a position to carry out or make the final decision on an option?

- Experience: Have they the experience and knowledge to judge whether, in reality, an option is viable?

- Having these people in the room can also be useful in forcing them to have a discussion they may have avoided, and to really explore the options.

- An experienced facilitator is highly beneficial to focus people’s attention and manage conflict over differing opinions.

2. Be clear what you’re prioritising and why

This may seem obvious, but starting off with the right question is vital: what are we prioritising and why? And what will we do as a result?

Firstly, knowing what you are prioritising will draw the line between what’s in and what’s out. For example, the extractives company only considered local social issues, unlike the sporting organisation which prioritised national issues.

Next, it is important for those involved to know ‘why’ things are being prioritised. For example, the sporting organisation prioritised social issues to decide which it should address through its own programs, whereas the extractives company wanted to know which it should invest in.

Finally, ‘what will we do as a result’ is key to avoid the prioritisation matrix being a waste of time or causing even more indecision. Will the matrix be an input into a further conversation, or will it be the basis for making a final decision?

If it is to be the latter, make sure you agree that whatever the outcome, you will trust the process. The sporting organisation had agreed upfront that it would choose which social issues to address from the top five priorities.

3. Agree parameters/criteria

Next, agree which parameters to use. Covey decided that importance and urgency are best the criteria to rank daily tasks. Commonly, in organisations which are assessing the issue or problem to address, the criteria most useful are; ‘size of the issue’ and ‘our unique ability to sustainably address it’.

The criterion, ‘our unique ability to sustainably address it’, is valuable as it essentially contains three conditions:

- We have the capacity to do it (knowledge and experience)

- We have the resources to do it (financial sustainability)

- We are uniquely placed to do it (no one else is addressing the issue adequately).

Almost always, options will not meet all three of these conditions and can thus be moved on the ranking accordingly. Having criteria with more than one condition can be helpful in deciding how far along the axis an option sits. Alternatively, having too many conditions may confuse the process.

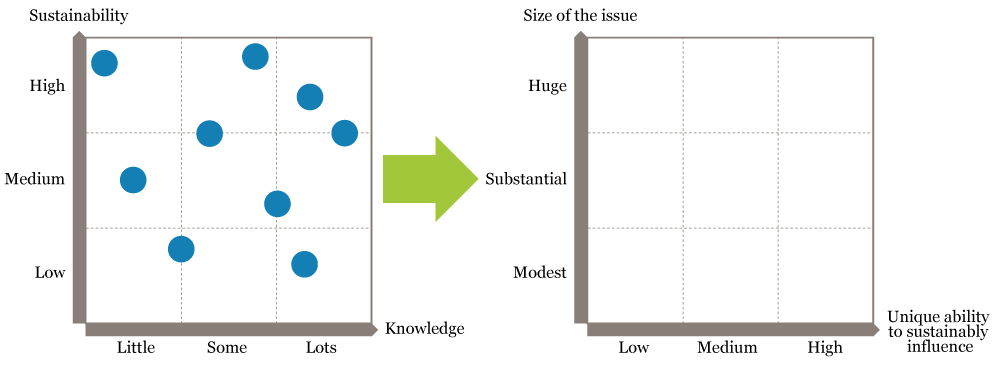

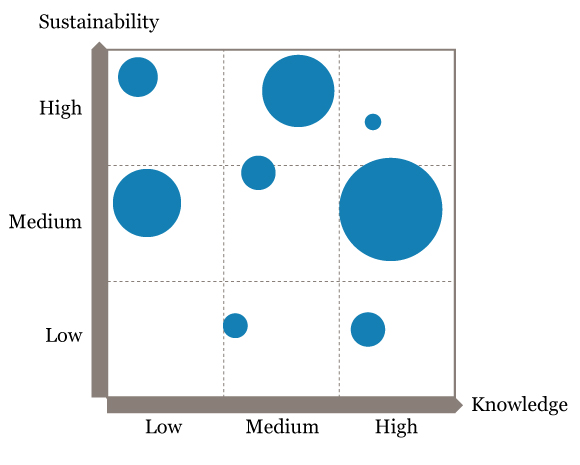

Furthermore, using criteria with many conditions also lends itself to having a number of linked matrices. For example, for a better idea of how an option may rank against the criterion of ‘our unique ability to sustainably address it’, you can firstly break that criterion up into several parts. As shown in Figure 7, a matrix using the parameters of ‘sustainability’ and ‘knowledge’ can be used to rank options against two of the three conditions.

Figure 7: You can link matrices: using one matrix to further break down one of the criteria.

4. Identify all options

The matrix works best when all options have already been identified; it is not a tool for identifying the options. Having all options under consideration results in:

- More confidence in the process: you are not left contemplating if an unidentified option may be better than your top priorities.

- Increased ability to rank options: with more options comes more opportunity to rank them against each other, essentially adding an extra dimension to the framework. For example, you may have ranked ‘unemployment’ as a big issue. Then, when deciding where to put ‘housing affordability’, you can compare it to the placement of unemployment and might base this on how many people are affected by these issues.

- Not needing to revisit the matrix.

If other options do subsequently emerge, they can be positioned in the existing matrix. Some CEOs have used a ‘permanent’ copy of an initiative or program prioritisation matrix to evaluate new ideas as they emerge.

5. If possible, build an evidence base

To make things easier in the next step (rank the options) try and build an evidence base. This is not possible in some situations, but even having a general idea of what is behind each option can be of great help. For example, the sporting organisation had the advantage of national statistics (such as economic cost) behind its options making it much easier to determine the size of the issue.

6. Rank the options

Once you know all the options and where possible have the related evidence, you can begin to rank them. Ranking can be the most difficult step, particularly if you do lack evidence. A few things can help this step go smoothly:

- Record your justification for the position of each option. This ensures that when someone not involved in the process (or even you later) looks at the prioritisation matrix, the reasoning behind where each option is ranked is clear.

- Acknowledge the subjectivity. Often ranking relies on a certain level of subjectivity being accepted. This can make people uncomfortable especially those used to basing decisions on facts. It helps to acknowledge the subjectivity and the possible discomfort.

- Acknowledge the flexibility of options. Options may need to be rearranged in response to how you rank a new option, as you are assessing each option against the others, as well as the criteria.

You can also rank options against each axis separately before plotting them. This is helpful when there are a lot of vested interests, or when different people have expertise on each axis.

Advantages and disadvantages of this tool

Advantages of a prioritisation matrix include:

- Nothing is out; things are just lower priority. All options are (at least) acknowledged as possible, which can help to avoid conflict about options being excluded.

- The visual presentation makes it easy to consider everything simultaneously. When there is a multitude of options to pick from deciding what to do can be overwhelming. Having all the options visually represented is easier to comprehend and digest.

- Quick and easy, and can be used when there are limited facts. As mentioned, the matrix can be helpful when there is a paucity of available data.

Disadvantages can be:

- Doesn’t exclude anything. As nothing is out, this can result in over complication with too many options cluttering the matrix.

- Subjective: Although also an advantage when there are limited facts, the inherent level of subjectivity can lead to doubts about the conclusion.

- Still difficult to manage more than a few dimensions. Having criteria with multiple conditions, such as ‘our unique ability to sustainably address it’ can help to deal with complex scenarios. Another way to manage an extra dimension can be to use different sized bubbles where appropriate. See Figure 8.

A prioritisation matrix can be an exceptional tool for making difficult decisions. By following the simple process outlined above, social purpose organisations will be able to address, and rank, complex options.

If you stick to the steps and trust the process, you will find yourself combining the science of evidence and the art of subjectively ranking options into one process; creating a new way of looking at situations.