A guide to outcomes contracting and social impact bonds

After 10 years of social impact bonds in Australia, we share insights and answer questions here in one place.

- Around two dozen social impact bonds (SIBs) and outcomes-based contracts have been deployed across Australia since the launch of Australia’s first SIB, the Newpin Social Benefit Bond, in 2013.

- Governments, service providers, intermediaries and investors have been consolidating learnings across contracts, simplifying approaches and working out ‘where to next’ for the funding model.

- The article summarises the current state of play and consolidates what we’ve learned over the past decade as covered in earlier SVA Quarterly articles: whether a program is suitable for a SIB, misconceptions about SIBs, how the development process could be streamlined, takeaways and conditions that are applicable to outcome-based contracts, and how SIBs are an important testing ground for policy development.

It’s been almost a decade since the launch of the first social impact bond (SIB) in Australia, the Newpin Social Benefit Bond. Since then, around two dozen social impact bonds and outcomes-based contracts have been deployed across the country to address a broad range of social issues.

The development of social impact bonds and outcomes-based contracts remains a largely government led process. While the ‘end goals’ for the projects implemented can sometimes be unclear, and the road to those goals can be convoluted, market participants – including governments, service providers, intermediaries and investors – have been consolidating learnings across transactions, simplifying approaches and working out ‘where to next’ for the funding model in the context of the broader service commissioning landscape.

What are outcomes-based contracts?

Outcomes-based contracting is an approach that governments use to commission a program for a clearly defined target cohort, with clearly defined outcomes. Not all programs are suitable for outcomes contracts – more on this below. Outcomes contracts have different names depending on the government jurisdiction, including payment by outcomes (PBO), social impact investments (SII), payment by results (PBR), and Partnerships Addressing Disadvantage (PAD).

Typically, the performance of the program is measured relative to a baseline or counterfactual and payments are linked to the program’s performance as measured by the agreed outcome metrics.

This type of arrangement generates a financial risk for a service provider relative to traditional government grant funding – if performance targets are not achieved, then the service provider won’t be paid to cover its cost of delivering the program.

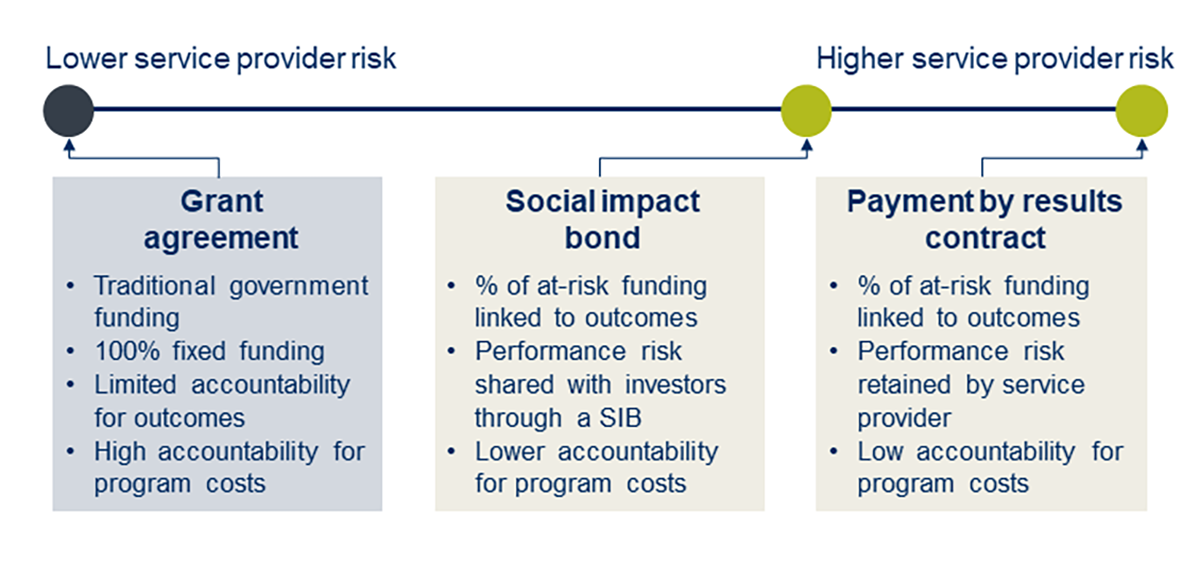

There are two key variations of outcomes contracts (see Figure 1). The key differentiating factor is who bears the risk that performance is not in line with expectations – investors, the service provider, or somewhere in between – as both variations have at-risk funding linked to outcomes.

Another feature of outcomes contracts is that they give service providers greater flexibility in how they deploy resources in the pursuit of the target outcomes during the term of the contract. Under traditional grant funding, there are usually detailed acquittals processes to report on the service provider’s expenditure of funding during the term of the contract. These either don’t exist or are more relaxed for outcomes contracts, hence there is lower accountability for program costs (but a high accountability for outcomes).

What are social impact bonds?

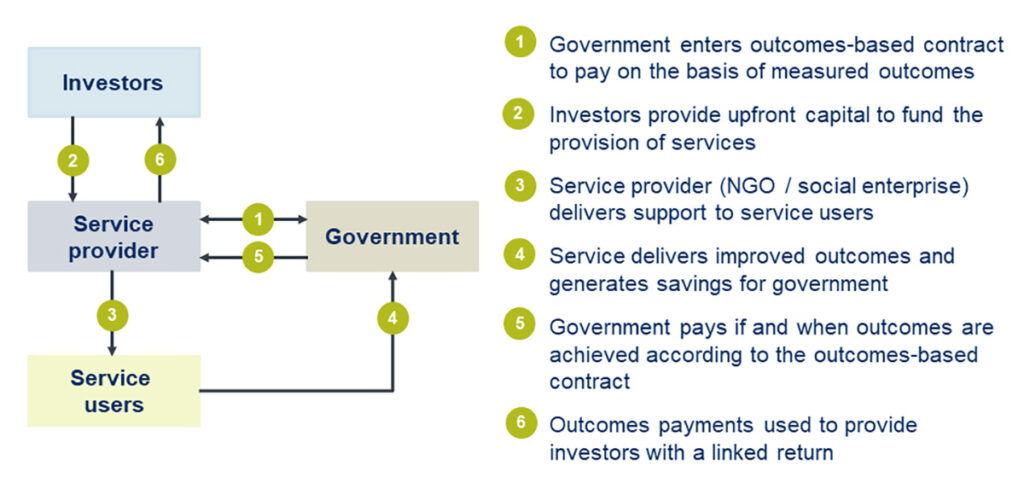

Where the risk profile of a ‘pure’ payment by results contract is greater than the risk tolerance of a service provider (i.e. the service provider could potentially incur a financial loss greater than it can accept), a SIB can be used to share the performance risk with (or shift the risk entirely to) investors. A SIB effectively provides the funding mechanism to enable the service provider to enter into an outcomes contracts with government. A SIB also provides the upfront working capital to fund the delivery of a program.

Figure 2 provides an overview of how SIBs can work (noting that different countries, legal systems and social programs necessitate variations on this structure).

Is your program suitable for a SIB or outcomes contract?

The article Is your program suitable for a social impact bond was published in 2015 as a practical guide to help organisations self-assess their program’s appropriateness for a SIB. There are many stars that need to align for a SIB to be viable, and article provides some ‘rules of thumb’ to consider that still hold true.

The key takeaways are:

- An outcomes contract has to satisfy government considerations, which will include whether there are potentially meaningful savings to be made, and a statistically sound, practical measure of those savings relative to a counterfactual is available.

- The potential program needs to be highly likely to deliver the outcomes at a cost commensurate with the benefits, with a sound program logic and evidence base.

- The program needs to be able to be delivered at scale large enough to generate statistically significant results.

- The development of an outcomes-based contract requires a material commitment of resources, and the delivery of the program involves a high level of governance and scrutiny.

- The risk/return proposition to investors needs to be sufficiently attractive to raise the required capital.

The current landscape in Australia and abroad

Outcomes contracting has largely been led by state governments in Australia over the past decade, with the Commonwealth Government commencing its social impact investing initiatives in 2017.

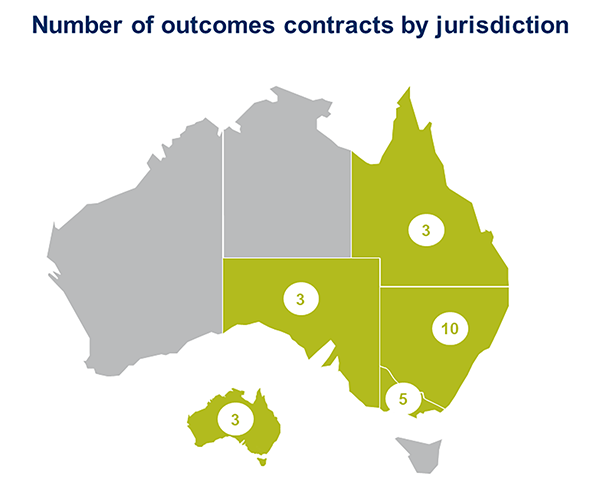

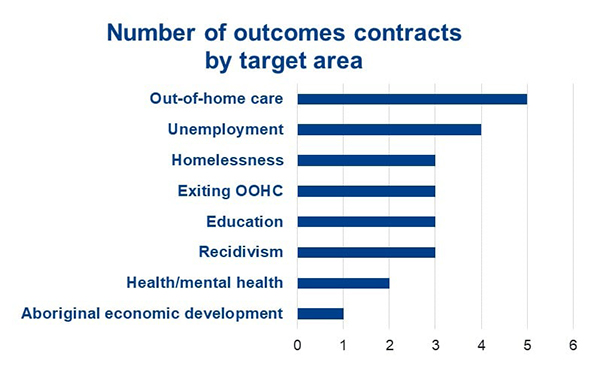

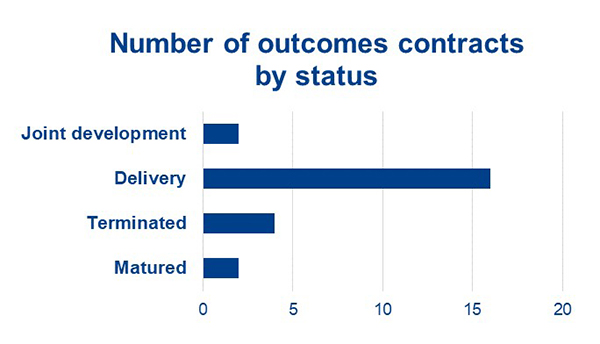

Figures 3, 4 and 5 summarise the number of outcomes contracts by jurisdiction, issue (target) area and status1. Around 24 outcomes contracts have been deployed or under development, of which 17 are social impact bonds or have an external risk financing arrangement.

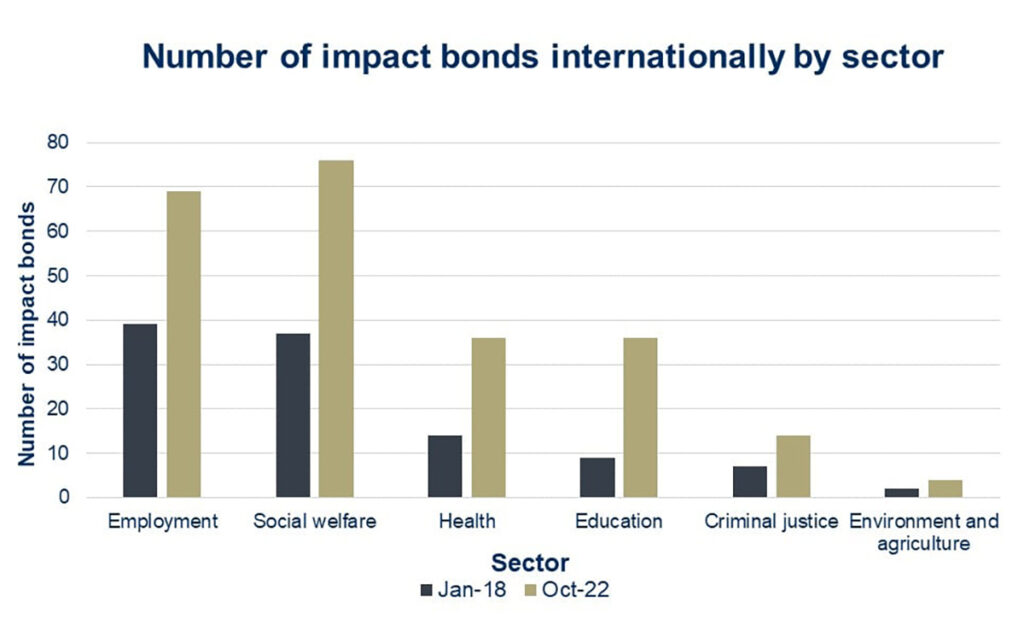

Since the launch of the first social impact bond pilot in the UK in 2010, 235 impact bonds (comprising 218 social impact bonds and 17 development impact bonds2) have been contracted in 38 countries across a range of sectors, with numbers more than doubling over the last five years. Figure 6 provides an overview of international impact bonds by sector.3

So, what have we learned over the past decade?

There are still many misconceptions about SIBs

After seven years of close involvement in Australia’s social impact bond market development, in 2019 Elyse Sainty shared her insights around SIB ‘myths and legends’ in Social impact bonds: a letter from the frontline – part 1.

These insights are still applicable today. Elyse explains:

- SIBs do not bring incremental money to the social sector, but they are a useful financing and risk-sharing mechanism for social purpose organisations entering into outcomes-based contracts with government.

- The complexity of SIBs lies in developing the basis for fair payments for outcomes, not the financing arrangement, so they are not materially more complex than ‘pure’ payment by outcomes contracts.

- Framing outcomes contracts as a tool to generate quantifiable budgetary benefits is too narrow: they can be used to improve the way services are procured and delivered; generate robust evidence; and enable governments to test new intervention models in a low-risk way.

SIB development processes could be streamlined and learnings applied more broadly

In part 2 of Elyse Sainty’s Letter from the frontline she sets out some views on the role that SIBs could play in the evolution of a system that focuses on what is important, uses evidence to shape responses, and delivers for the community – and how to make the path to that vision a little easier.

Elyse discusses how:

- The discipline imposed by an outcomes-based contract can be a powerful catalyst to use data for good, and transparency helps us learn from our collective successes and failures.

- The development of outcomes contracts can be lengthy and expensive, but that can be significantly simplified if governments’ ‘front end’ the analysis of baseline outcomes and the selection of metrics, including developing outcome data extraction capability. There is a danger that overly complex contracts, governance and evaluation will stymie the evolution of SIBs.

- It is important that an outcomes contract is seen as a means to an end, with a clear view of ‘what happens next’ at the conclusion of the project.

There are key takeaways and conditions that are generally applicable to outcomes contracts

The Newpin4 family reunification program has been deployed under the SIB mechanism in three states. The Newpin Social Benefit Bond in NSW was Australia’s first SIB, and it matured in 2020. Over seven years, 61% of children were restored, almost three times the counterfactual. Replication of the model in Queensland was less successful, and the bond terminated early. The Newpin SA SIB launched in 2021, and has achieved promising early results. The article, Social impact bonds: a tale of three Newpins, draws out some of the learnings from comparing the experiences across the three projects.

This article highlights that:

- An in-depth analysis of the eligible population is critical to ensuring that there are sufficient people in the program’s catchment area to meet planned numbers. Effective ‘triaging’ is also required so the right people are introduced to the right program at the right time.

- Parties in an outcomes contract should be held accountable for what they have the power to deliver – but no more.

- The counterfactual against which program performance is measured should be as simple as possible – provided it is still fair.

- Ongoing nurturing of relationships and recapping of project objectives and mechanics should be deliberately undertaken at both governance and operational level.

- Allowing time for a program to get into a rhythm is important so that early results don’t disappoint. Implementation risk needs to be specifically considered.

- When things don’t go to plan, clear documentation and a shared objective can go a long way to finding a positive way forward. But if common ground cannot be found, all parties need an exit path.

SIBs are an important testing ground for development of broader policy

The latest results and recent evaluation of the [Aspire SIB] contributes to a growing body of evidence backing the highly supportive Housing First approach5. In the article, Housing First: the challenges of moving from pilot to policy, Pat Bollen explores the barriers to this approach being funded and adopted more extensively across Australia. Many of these challenges are applicable to other SIBs and programs which demonstrate positive results for individuals and governments, but have not yet been embedded within the policy and service delivery landscape.

This article outlines:

- SIBs, through measured results and broader evaluation, contribute to the evidence base of intervention models that are effective for defined cohorts – for both individuals and governments.

- Misalignment between the ‘cost centres’ and the ‘savings centres’ for more ‘expensive’ intervention models (relative to the crisis care-oriented services) can make it difficult for one government agency alone to build the economic proposition that the initiative stacks up.

- Existing service systems are complex, with multiple barriers to reform. Implementing or scaling proven intervention models such as Housing First requires detailed strategic planning founded in understanding demand and the drivers of the social problem being addressed, consideration of implementation options, and a focus on supporting system transition.

- There are often external challenges (e.g. chronic shortage of affordable housing for Housing First approaches) that are significant challenges to implementation and require multi-faceted responses.

Authors: Patrick Bollen and Elyse Sainty

- Data is based on information available to SVA, may not reflect recent developments and only includes contracts with key ‘outcomes-based contract’ features outlined in this article.

- Development impact bonds are typically issued in developing nations and the funder is a philanthropic organisation instead of government.

- International social impact bonds by sector. (Source: Brookings Institution global impact bond database snapshot, October 1, 2022) Social welfare includes impact bonds addressing homelessness, poverty reduction, and child and family welfare.

- The Newpin program works to restore children in out-of-home care to the care of their parents. It works with parents through a trauma-informed lens to enable them to create a supportive and safe family environment.

- Housing First is an approach to housing and supporting people experiencing chronic homelessness, incorporating intensive case management and specialised supports alongside permanent housing. The Aspire SIB evaluation found that the Aspire program was highly effective, especially for people with complex needs for whom more conventional service delivery approaches tend not to deliver sustainable benefits. The evaluation found that the key innovative features of Aspire – the intensity of supports, the flexibility to tailor supports, and the long duration of supports – were unlikely to have been possible without the resourcing levels provided by the SIB.