Accessing PAFs: six rules of engagement

Fiona Higgins from Australian Philanthropic Services illuminates the realities of private ancillary funds (PAFs) and what it takes to position your organisation for that serendipitous alignment.

- While the charitable distributions of PAFs already exceed $300 million annually, individual PAF distributions average roughly $200,000 annually, and often occur in tranches of $5,000-$20,000 per not-for-profit (NFP).

- PAF funding is a rare source of untied funding, often in the first five years of a NFP’s life, and is generally less risk-averse and more flexible than other sources.

- The PAF-holders’ passion and personal experience plays a large role in decision-making; NFPs will not be able to sway PAF holders solely on the strength of their impact per se – though this can be important where multiple organisations are working in the same space.

- The six rules of engagement are: be clear about the ask, be realistic about the opportunity, woo the intermediaries and advisers, go to industry events and nurture the relationship with the PAF once you have one.

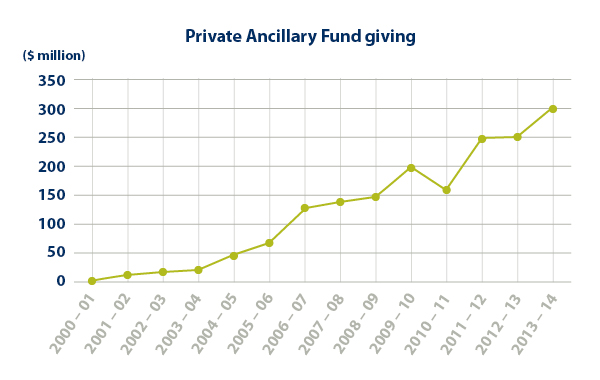

How do I unlock the PAF market? What do PAFs want? How do I get in front of PAF decision-makers? These are common questions from not-for-profit (NFP) entities wishing to find meaningful ways to engage with private ancillary funds (PAFs) in Australia. The imperative for engagement is clear, with some 1,500 PAFs now boasting combined assets of more than $10 billion. Their charitable distributions are rising too, and already exceeds $300 million annually.

… structured philanthropy still represents a modest eight cents in the social change dollar.

These figures reflect rising levels of philanthropy in Australia generally, structured or otherwise. The most recent ATO tax statistics (for the 2014-15 year) show encouraging signs that individual philanthropy continues to gain traction, with total deductible giving by taxpayers increasing by 18% to over $3 billion. Importantly, 75% of this increase came from the wealthiest Australians (those with total incomes of over $500,000). Even more encouragingly, those with incomes over $1 million donated the equivalent of 3.4% of their taxable income in 2015, up from 2% the previous year.

Still niche funders

While a boost in donations to ancillary funds was part of the uplift in total giving, it is important to recognise that structured philanthropy still represents a modest eight cents in the social change dollar.[1]

There is animated discussion about the possibilities of intergenerational wealth transfer over the next 20 years – with NFPs hoping that baby boomers will follow Warren Buffett in leaving a negligible portion of their estate to their children in favour of charities. However, some observers remain skeptical: ‘If [even] three-quarters of everything is going to the kids, that puts [an end] to our sector’s hopeful notion that a huge intergenerational transfer of wealth would produce a tidal wave of charity.’[2]

Even after possible growth, PAFs will not be a funding mainstay for NFPs: it typically takes government to scale.[3] However, PAFs occupy an important niche in the overall funding ecosystem as providers of social risk capital, often instrumental in funding new approaches to long standing challenges. In our experience at APS, they also offer a rare source of untied funds often in the first five years of NFPs’ existence, to grow or strengthen entities and to refine operational models.

Structural and cultural barriers to access

PAF funding is generally less risk-averse and more flexible than most government or corporate funding, so many NFPs understandably see PAFs as an attractive partnership proposition. However, in learning more about PAFs and their philanthropic priorities, NFPs usually encounter a range of explicit and implicit obstacles.

… many smaller PAFs still retain or foster a culture of low-key, make-it-happen humility.

For starters, there is little information on PAFs in the public domain. While fundraisers would like an accessible register of PAFs, there is no such thing. PAFs must be endorsed by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to receive charity tax concessions and be registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC), but the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Regulation 2013 (Cth) specifically allows PAFs to ask the ACNC to withhold or remove some of this information ‘where it is likely to identify individual donors’. PAF reportage to both the ATO and ACNC is rigorous, but its inaccessibility presents an obvious challenge to those charged with business development and fundraising for NFPs.

While some observers claim that private philanthropy in Australia has ‘cast off its cloak of secrecy and is now coming out loud, proud and generous’,[4] many smaller PAFs still retain or foster a culture of low-key, make-it-happen humility. This commitment to a ‘below the radar’ style of philanthropy – as frustrating as it may be for NFPs – is arguably a defining characteristic of PAFs.

… there is little consensus on what transparency constitutes…

Some in the sector respond by calling for increased or mandated public transparency for PAFs, to facilitate greater exchange of information between funders and NFPs: ‘… if there’s a tax treatment given to permit private wealth to be used for public good, then there’s some obligation or intrinsic value in making information about how that is being done, public.’[5]

Others refute such calls, underlining that there is little consensus on what transparency constitutes, and that it is ‘not at all clear why philanthropic enterprises should voluntarily pursue degrees of transparency more aggressively than is required by law.’[6]

In any discussion about increased transparency for PAFs, it is useful to recall that the prime purpose of the ACNC charities register is to allow potential donors and volunteers to check out a charity before they commit to supporting it: PAFs legally cannot solicit public donations and don’t require volunteers.

What cannot be disputed is that philanthropy and the giving culture in Australia has been advanced by the creation of PAFs and the ACNC.

How should NFPs engage with PAFs?

Many NFPs underestimate the role that passion and personal experience play in PAF decision-making. In most cases where a long-term, mutually beneficial partnership is struck between a NFP and a PAF-holder, the latter’s personal passions usually align closely with the NFP’s mission. Often this has been determined after a fortuitous or serendipitous meeting between leaders of both. This almost magical combination cannot be anticipated, and can almost never be forced.

NFPs are unlikely to win using an ‘impact argument’, however well-constructed.

Because of this, NFPs are unlikely to win using an ‘impact argument’, however well-constructed. This does not mean that NFPs should abandon impact measurement when approaching PAFs. On the contrary, where multiple charities are working in the same space, clarity around impact can be a determining factor.

Keeping this in mind, here are six rules of engagement for accessing PAFs:

1. Be clear about the ask(s). Think about what PAF funding is best applied to – in our experience, catalytic social risk capital in the first five years – and compare that against your entity’s needs. Apart from outright donations, consider any other ‘asks’ you may have: many PAF holders seek to contribute beyond dollars alone, using their expertise, skills and networks to support the charities in which they are involved. Have a wish-list prepared before you contact intermediaries, advisers or individuals associated with PAFs. Avoid overtures offering PAF holders ‘a general briefing’ on your work.

… the average PAF is distributing roughly $200,000 annually… in tranches of $5,000-$20,000 per organisation.

2. Be realistic about the opportunity. Despite the publicity around mega-givers such as the Forrests, John Grill, Clive Berghoffer and the Tuckers, private ancillary funds are not the exclusive domain of high-profile business people and billionaires. APS sees people from all walks of life setting up PAFs – and they don’t necessarily have tens of millions at inception. The average PAF in Australia is estimated as having around $1-3 million in its corpus, of which a minimum of 5% must be distributed to eligible charities every year. This means that the average PAF is distributing roughly $200,000 annually and, in our experience, this often occurs in tranches of $5,000-$20,000 per organisation. Therefore, charities that imagine PAFs to be a panacea for their funding problems – readily handing out grants of $100,000 upwards – are likely to be disappointed.

3. Woo the intermediaries. Many PAFs are managed or administered by a handful of well-known entities, such as Australian Philanthropic Services (APS), Perpetual, Mutual Trust/Myer – so it makes sense for NFPs to reach out to those entities. It pays, however, to research the modus operandi of these entities before you make contact, as these are very different. For example, Perpetual has a structured annual grant round for NFPs (closing on 8th December 2017 for 2018 funding) whereas PAFs using APS generally drive their own grantmaking decisions. Instead, APS offers a year-round expression of interest form that charities can submit via the APS website to ‘get on the radar’ of PAFs.

4. Woo the advisers. Intergenerational wealth transfer remains a potential opportunity. It makes sense for NFPs to cultivate relationships with wealth management, advisory firms and private banks that offer philanthropic services. According to Catherine Tillotson of Scorpio Partnership, a London-based market research firm to the wealth management industry, the millennial generation ‘is more receptive to advice on their philanthropy than previous generations’.[7]

5. Go to industry events. It may seem arbitrary and unscientific (and it is), but being in the right place at the right time is the genesis of many strategic partnerships. If you don’t attend the biennial Philanthropy Australia conference, the annual Generosity Forum or sector-specific gatherings such as those hosted by the Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network and The Funding Network, you reduce your chances of meeting officeholders of PAFs and other private philanthropic vehicles.

… when you do receive funding, say thank you and maintain the relationship.

6. Nurture the relationship. PAFs are relatively new in Australia. Most are still being run by the Directors who founded them. This does not mean that they are ineffective; instead, they are simply unlikely to have staff running the foundation, or to be bogged down with bureaucracy, process and reporting. This means that decisions can be made promptly, without protracted consultation, and sometimes even without much more than a concise summary of a NFP’s needs. While some PAFs have formal funding rounds, most don’t: chances are, you will be cultivating a relationship directly with the PAF founder or immediate family members. Engagement is important: when you do receive funding, say thank you and maintain the relationship. Keep the funder updated, invite them to see your work in action and don’t be afraid to ask again in the future.

Will it always be like this?

Since PAFs were first introduced by the Federal Government in 2001, the sector has matured. Existing PAFs are growing larger, new PAFs are being established apace and more PAFs are opting to ‘go public’ with their giving. PAF holders are generally more knowledgeable about, and engaged with, the NFPs they fund. PAFs are able to intervene spontaneously where other funders cannot, and many PAFs choose to focus on areas overlooked by government, or to support slightly riskier or untested ideas offering new ways to respond to some of society’s most entrenched problems.

PAFs are mostly driven by personal passions and serendipitous alignments.

Despite this evolution, a fundamental opaqueness lingers. In addition to the prevailing PAF culture of privacy and humility, PAFs are mostly driven by personal passions and serendipitous alignments. These sectoral specificities are unlikely to shift any time soon – and nor should they, some would argue. Private philanthropy is not government or corporate funding, after all.

At their core, PAFs are idiosyncratic: their only guaranteed commonality is their structure. There is no homogenous ‘market’ represented by PAFs, nor common areas of philanthropic interest. While NFPs need to be realistic about the degree to which they can influence PAF holders, those that observe the six rules of engagement are likely to improve their prospects of forging meaningful partnerships with mission-aligned PAFs.

Author: Fiona Higgins

Fiona Higgins is Grantmaking Specialist at Australian Philanthropic Services, an independent not-for-profit organisation that establishes and administers private and public ancillary funds and provides grantmaking advice.

[1] S. Davies, Contemporary Philanthropic Practice. Brisbane seminar, 29 August 2017.

[2] P. Panepento, Are Charities Losing Out on the Wealth Transfer? The Chronicle of Philanthropy, 7 August 2017.

[3] S. Davies, Contemporary Philanthropic Practice. Brisbane seminar, 29 August 2017.

[4] L. Schmidt, Philanthropy Comes of Age in Australia. The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August 2014.

[5] N. Richards, Greater transparency in philanthropy is inevitable: Brad Smith. Generosity Magazine, 5 May 2016.

[6] J. Tyler, Transparency in Philanthropy: An Analysis Accountability, Fallacy and Volunteerism. The Philanthropy Roundtable, 2013.

[7] Fondation de Luxembourg, Engaging the Next Generation through Philanthropy. Luxembourg seminar, 11 July 2017.