Disability housing: what does good look like?

SVA has partnered with the disability sector to co-develop a common outcomes framework for disability housing that is both meaningful and practical. What is the framework, why was it developed, and what does it mean for people with disability?

- SVA Consulting has teamed up with the disability sector to develop a common outcomes framework which will help the sector better understand the impact of housing and in-home supports on the lives of people with disability.

- The work has been guided by a coalition of industry providers, with regular input and advice from people with disability, representative and industry peak bodies, disability service and housing providers, and academics to ensure it is meaningful and practical.

- The Disability Housing Outcomes Framework (the Framework) encourages providers to look beyond compliance towards what good looks like to set a standard across the industry

- The Framework has been completed and is freely available across the sector under a Creative Commons License and can be accessed here.

- The focus of work for 2021 is to codesign and pilot a tool for providers to use to consistently collect data, and to provide opportunities for sector learning and benchmarking over time.

Access to appropriate and affordable housing is a key driver to enable people with disability to be full and equal participants in society.1 Yet while the stock of specialist disability housing has grown over the last few years,2 the sector’s understanding of how these homes facilitate better outcomes once tenants have moved in has remained limited.

SVA Consulting has teamed up with the disability sector to develop a common outcomes framework to help better understand the impact of housing and in-home supports on the lives of people with disability.

This article explores why the sector needs an aligned approach to measurement, how the Disability Housing Outcomes Framework (the Framework) was developed, and how it will be piloted while ensuring that data collected is meaningful, practical, and will guide better decision making.

The difference a good home makes

After experiencing a stroke, Kevin spent two long years in a rehabilitation hospital unable to find housing that suited his needs. He finally found disability housing developer Good Housing and in early 2021 moved into his purpose-built villa3 in Mount Colah, Sydney. Kevin now describes his home as his sanctuary.

“I’m so comfortable now, I forget I’ve had a stroke.”

“Living in my villa means that I have freedom and choice to do what I want to do, when I want to do it. I can choose to be at home, or go out into the community with no restrictions. My friends can come and visit me. I am surrounded by my possessions and have chosen how my home is furnished.

“My life has returned to normal, and because of that – this is strange sounding, but it’s true – I’m so comfortable now, I forget I’ve had a stroke.”

The disability housing market

The disability sector is changing rapidly, with increasing emphasis on putting people with disability at the centre of the system. With the rollout of the NDIS and the significant differences in the way supports are funded, people now have greater power to purchase the services and supports that are best suited to their needs. With a proliferation of service providers, people with disability have more choice than ever before.

… providers have limited resources… and need to allocate those resources effectively to maximise impact.

As a result, they, and their families and carers, are seeking more information from service providers to inform decision making. Organisations with the ability to demonstrate their impact are starting to have an edge in attracting and retaining customers. However, providers have limited resources (particularly given the slim margins under the NDIS price guide) and need to allocate those resources effectively to maximise impact.

In addition, the housing system for people with disability is complex and involves diverse, specialised stakeholders that each respond to different needs and service demands.

Meanwhile, there has been a steady increase in private investment in disability housing, driven through funding for Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA).4 With SDA payments expected to total approximately $700 million per year, there is the potential to stimulate around $5 billion in private sector investment.5

A common outcomes framework for disability housing

Consistently across the sector, stakeholders have been asking ‘What does good look like when it comes to disability housing?’

As Ian Maynard, Chair of industry body, the SDA Alliance,6 says, “There’s been a generational shift in the choice and control that Australians with a disability have around where they live and who they live with.

In July 2020, SVA Consulting brought together a coalition of stakeholders to address this question by working to develop a common approach to understanding and demonstrating the impact of housing on people with disability.

“The challenge with the wide range of innovative solutions we are now seeing in disability housing is to capture data that will ultimately result in evidence to support what good practice looks like.”

This work was only possible thanks to a collaborative partnership of stakeholders from across the sector.

The steering committee which funded and guided this work was made up of SDA providers (DPN Casa Capace and Good Housing), community housing providers (BlueCHP and Housing Choices Australia), and Supported Independent Living (SIL) providers7 (Aruma, Claro, and Life Without Barriers). In addition, people with disability, representative peak bodies, the SDA Alliance, academics , and other stakeholders from across the sector were regular contributors. Synergis Fund provided additional funding.

“Everything is very opaque at the moment regarding what is good.”

BlueCHP got involved in the collaboration for two main reasons, says CEO Charles Northcote.

“First is to give participants confidence in the house that they’re going to live in and ensuring their interests are looked after.

“Second we need some standards. Without performance benchmarks we could head back down the road we’ve already seen with royal commissions in disability. Everything is very opaque at the moment regarding what is good.”

For Maynard, “The housing outcomes framework is a vital tool that will enable the sector and participants to be able to gather the data to support the evidence behind their preferences and behind better models of practice.”

The impetus for the Framework was to understand the impact of SDA specifically. However, as the conversations evolved, stakeholders identified that it may have benefit in the future for understanding the impact of housing more broadly to facilitate good outcomes for people with disability.8

Furthermore, most people eligible for SDA are also eligible for SIL, along with other formal and informal assistance.

“The Framework will give us a reference point to see how people feel about how they’re being looked after.”

Many of the design and build features work hand-in-hand with in-home supports to facilitate good outcomes for people with disability. As such, it soon became clear that understanding the impact of housing on the lives of people with disability required the consideration of both the built-form (SDA) and the in-home supports (SIL).

Northcote explains that as a housing provider, BlueCHP is slightly removed from day-to-day caregiving.

“The Framework will give us a reference point to see how people feel about how they’re being looked after. And it provides opportunities to discuss matters with the SIL if there are issues.

“On a bigger scale it means that families, guardians and others are seeing some independent reference point on the care and housing provision,” says Northcote.

As the sector moves to separate the provision of housing from that of supports, there is a need to understand responsibility and accountability between different providers. Safety, security, and relationships with people living in homes is the responsibility of both housing and support providers, as well as the person themselves and their family and carers.

“The Framework tries to provide a common language for SIL and SDA providers… to help them put participant care at the forefront…”

Federal government does not yet have a clear position with regards to explicit accountabilities, and providers are confused. While providers recognise there is significant benefit in collaborating to deliver the right supports and outcomes, they are not sure how best to work together.

Northcote explains that working together is at the heart of the framework.

“The Framework tries to provide a common language for SIL and SDA providers who are of like minds to help them put participant care at the forefront in their conversations, joint arrangements and joint delivery of outcomes for the client,” says BlueCHP’s Northcote.

The importance of measuring outcomes

With a rapidly changing funding environment, growing expectations and limited resources, it is critical to measure outcomes.

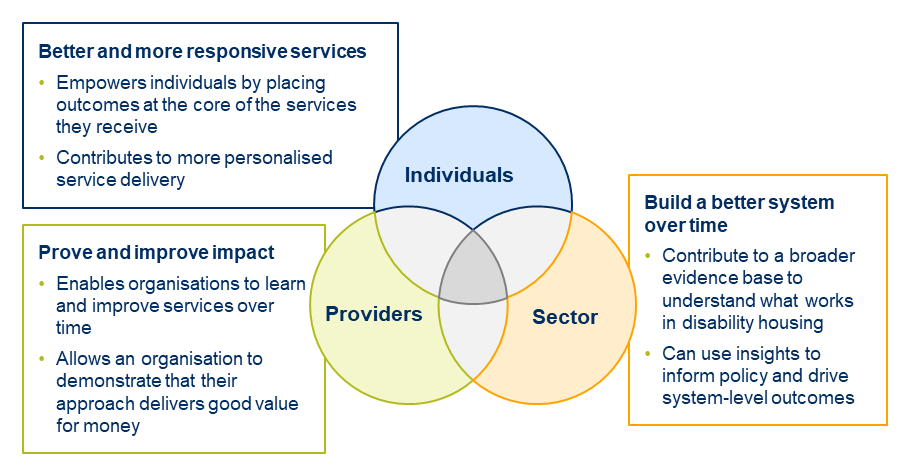

Our experience tells us that impact measurement can help create better and more responsive services, empowering individuals by placing outcomes at the core of the services they access. It helps providers to prove and improve their impact over time and contributes to a broader evidence base to understand what works across the sector to build a better system over time. (See SVA’s Guide to Social Impact Measurement)

But outcomes measurement is hard. It is difficult to know what good looks like, and there is little consistency across organisations in the systems and methods used to collect and analyse data. In this environment, it is challenging to compare and learn from one another about what works to guide development of the market.

Many existing outcomes frameworks and tools are not appropriate to prove and improve the impact of disability housing. While existing frameworks have some strengths, including being clinically validated and rigorous, with robust methodology, they are often not fit-for-purpose to the NDIS environment in Australia. The surveys and tools can take too long to administer (from 15 minutes up to two hours) and they can also be expensive, making them difficult to conduct on a regular basis. Furthermore, often the feedback is not actionable; a significant time lapse between data collection, analysis, and feedback limits the ability for providers to use the information to make service improvements or address critical issues as they arise.

“Having a consistent measurement mechanism gives us insight into our impact and how we can improve.”

An industry-led approach driven by a commonly identified need was critical. This ensured expectations and energy aligned to drive a fit-for-purpose approach.

Michael Fuller, Executive Director and CEO of SDA provider DPN Casa Capace, says that having real social impact is one of the core reasons that the company entered the SDA market.

“Having a consistent measurement mechanism gives us insight into our impact and how we can improve. It helps us understand both what we are doing but also helps us to see best practice by other leaders in the sector.”

Person-centred and practical

To date, a key to the Framework’s buy-in across the sector has been ensuring that it was developed by those who will use it. This ensures it is both meaningful for people with disability and practical for providers to implement, as well as informing decision making for all parties.

“When those objectives are met the overall sustainability of the NDIS as a scheme should be improved.”

Maynard explains that the Framework has two real beneficiaries. “The first are the participants who will have increasing evidence to support their housing preferences.

“The second is the sector which will get necessary guidance to be able to invest in the right models, dwelling types and the best practice approach to care that meet the needs of the sector.”

“When those objectives are met the overall sustainability of the NDIS as a scheme should be improved.”

To ensure buy-in the coalition’s approach was based on a set of guiding principles. These principles were developed with the steering committee and based on guidance including from disability, housing, and impact measurement experts.

Extensive consultation

The Framework has been developed through widespread consultation with many stakeholders, building off existing evidence and frameworks.

Over six months, SVA Consulting worked intensively with more than 80 individuals representing over 45 organisations including people with disability, SDA and SIL providers, representative and industry peak bodies, academics, and funders to codesign, test, refine, and retest the Framework. They participated in ongoing workshops, interviews, and reviews of draft documentation, as the team built off existing outcomes frameworks and evidence of what works.

Libby Callaway is Associate Professor at the Rehabilitation, Ageing and Independent Living Research Centre at Monash University. She knows that “It’s really important to start with the person in the centre, hearing from people who are choosing housing, and then planning for support. And that has been the focus with this work.”

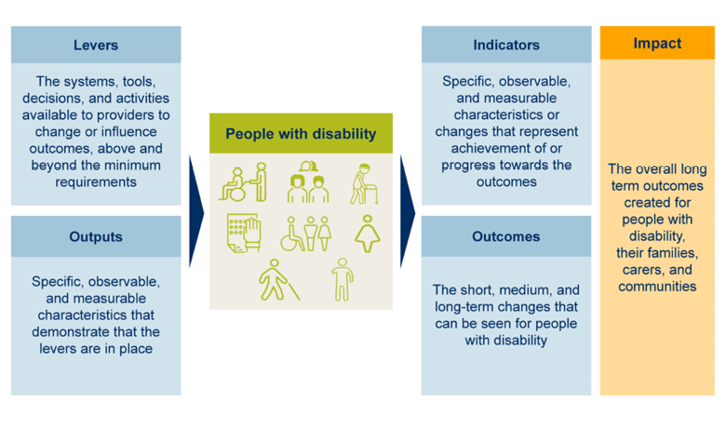

The Framework architecture (Figure 2 below) considers the link between the activities of providers (levers) and the changes these facilitate for people with disability (outcomes). The Framework encourages providers to look beyond compliance towards what good looks like to set a standard across the industry and assumes all minimal legal and financial obligations are already being met.

What matters most for people with disability

The outcomes and indicators have been developed and prioritised based on what matters most for people with disability, and what is most helpful for providers to measure.

Three key questions were considered in determining which outcomes, indicators, and levers to include.

- Is it meaningful for people with disability?

How does it consider the diverse experiences and contexts of people with disability including cultural background, type of disability, location, and age? - Is it useful for providers to prove and improve what they are doing?

How can the Framework provide meaningful data to track progress over time, as well as enable providers to respond rapidly to issues as they emerge? - Is it practical to implement?

Can data collection be simplified to ensure it is not burdensome for people with disability and their formal or informal supports?

The outcomes

The Framework centres around six outcomes which reflect core NDIS values of choice and control, and what matters most for people with disability to live a good life.

Based on answers to these three questions, the following outcomes were identified and agreed on by the broad coalition:

- Daily living: People with disability are in control of their daily living routines

- Health: People with disability are physically, mentally, and emotionally healthy and can access health services

- Relationships and community: People with disability have healthy relationships at home and are connected to their community

- Rights & voice: People with disability can exercise their rights and responsibilities and have values roles in community

- Independence: People with disability have choice and control over decisions about their lives

- Stability & safety: People with disability are comfortable in their home and safe from physical and psychological harm.

There are many challenges implementing outcomes frameworks and data collection within and across organisations. As a result, it was agreed that the Framework needed to include the minimum possible number of indicators to inform decision making, but no more than necessary.

The intention is that all providers adopting the Framework will measure against these eight indicators as a minimum.

Based on this, eight common indicators were selected to understand progress towards the six outcomes, including both self-reported and observable measures. These indicators were developed, prioritised, and agreed with the sector from a long list of potential indicators, and include a balance of subjective and objective measures across the Framework.

The intention is that all providers adopting the Framework will measure against these eight indicators as a minimum. If they do, there is an opportunity to ‘compare like with like’ and facilitate learning across the sector. (There are additional indicators for organisations who have an interest in deeper engagement with their work and the Framework to understand their impact.)

Importantly, the outcomes and indicators are interrelated and themselves relate to a person’s life experiences, needs, and aspirations. Therefore, interpreting the data collected and the indicators cannot be done in isolation and must be done with consideration of a person’s unique context as well as the broader ecosystem and policy environment.

Providers influence outcomes

Housing and support providers can enhance outcomes for people with disability through their activities, decisions, and ways of working.

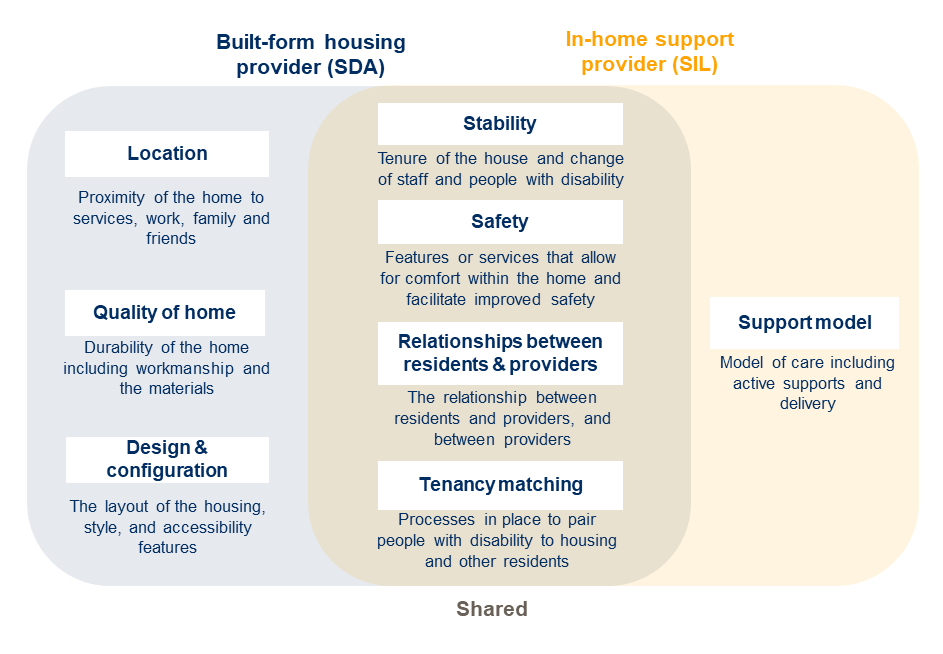

Through the development of the Framework, stakeholders consistently identified eight key levers which housing and support providers can use to facilitate or enhance good outcomes (see Figure 3 below). These include the location, quality, and design of the home; safety features; the relationships people with disability have with their providers; stability; who people live with; and the support model in place. To enable good outcomes for people with disability, providers need to understand how to activate these levers either alone or in partnership.

Some levers therefore include ‘shared’ responsibilities.

Levers related to the development and management of the built form of the home fall within the control of the developer and built-form housing provider.

Levers related to the support fall within the remit of the in-home support provider. There are also levers that providers need to collaborate on: tenancy matching, safety, stability, and the relationships between providers and the person. Here the level of control and influence is less clear.

Although one provider may have more control over a lever, other provider(s) can also influence or enhance its impact. Some levers therefore include ‘shared’ responsibilities. For example, safety is influenced not only by the built form of the home such as its fire resistance and fire alarm systems etc, but also the supports including any assistance required to help a person escape the building. There is significant diversity of needs, preferences, and aspirations of people with disability. So the ways in which outcomes are achieved will look different for different people. Recognising this, the Framework provides examples of outputs that providers can use to facilitate or enhance good outcomes for people with disability, without being prescriptive.

For example, for Kevin, who describes himself as very sensitive to his environment, the relationship with his providers is a priority, as is being able to choose who works with him.

“It’s very important to me to feel good with the people around me,” says Kevin.

“People’s goals change over time like all of us.”

These levers and outputs will be reviewed and revised over time as the evidence base grows to understand what works for people in different contexts.

The Framework also accommodates people’s needs and aspirations changing.

As Callaway says “People’s goals change over time like all of us. You set a goal. You achieve that goal. Then you set a new goal. So when you’re talking to people about outcomes, it is really important to understand that that’s going to be a changing environment.”

Supporting meaningful decisions

Underpinning this Framework is the importance of enabling people with disability to make meaningful decisions.

An outcomes framework is only as good as the data that is collected. The data will be most useful if people with disability are supported to understand their options, communicate their preferences, and provide honest feedback. People with complex communication needs must be appropriately supported to not only achieve their goals, but also participate meaningfully in the data collection. Some people with disability may require support to understand their options and make meaningful decisions, including through supported decision making.

As Northcote says, “We have to recognise that clients’ capacity and ability to communicate can vary; we have to keep it very basic and simple to be able to create standardised benchmarking.”

“The Framework is a way for us to get an indicator if anything is going wrong or if things are going right. It provides a lead indicator before problems manifest themselves.”

“What will be key is benchmarking the standards.”

The Framework’s implementation will also consider existing continuous quality improvement, feedback, and risk management processes for providers to track and improve outcomes. The specifics of how the Framework and associated tools will be rolled out is being developed and piloted during the next stages of work. This includes considering how best to support people to provide data and feedback on their experiences, whilst not being overly intrusive or burdensome.

Northcote believes that “Most people who operate in this space are used to this sort of thing: customer satisfaction, net promoter scores, etc. are part of standard practice.

“What will be key is benchmarking the standards. We want to get to the point where if you say ‘x is x’, everyone agrees what x is.”

Where to from here?

The Framework has been completed and is freely available across the sector under a Creative Commons License,9 and can be accessed here. The Framework is a living document, which will be reviewed and updated over time as our understanding as a sector grows.

The focus of work for 2021 is to codesign and pilot a tool for providers to use to consistently collect data, and to provide opportunities for sector learning and benchmarking over time.

“We hope this provides a basis for participants to be able to make more informed choices…”

Maynard hopes that all providers of disability accommodation will adopt the framework and work with their participants to enable them to contribute evidence into that framework, so that it will be an excellent comparator between different service models and different providers.

“We hope this provides a basis for participants to be able to make more informed choices based on others’ experience with that service provider.”

The tool will be piloted initially with a select number of housing and support providers, including the current steering committee. They will test the tool and processes to ensure the data collection process is not overly burdensome and the data is meaningful and can inform decision making. From there, the tool will be further refined and made available to the sector more broadly.

To find out more about the Framework and opportunities to get involved, visit the website: www.disabilityhousingoutcomes.com

1 Disability perspective paper, SVA

2 Specialist Disability Accommodation Supply in Australia, Summer Foundation & Housing Hub, Jan 2021

3 The Specialist Disability Accommodation villa was developed by Good Housing and was funded and is owned by the Synergis Fund.

4 SDA is accommodation for people who require specialist housing solutions, including to assist with the delivery of a high level of supports. SDA does not refer to the support services, but the homes themselves. For more information about SDA, see Where to next for SDA?

5 SDA Explainer for investors, Summer Foundation, Dec 2020

6 A coalition of SDA providers and investors

7 Suppliers of paid personal supports under NDIS

8 Only approximately 6% of NDIS participants are eligible for SDA, with the remainder living in non-SDA disability housing, social housing, aged care homes, and in the private rental market.

9 The Disability Housing Outcomes Framework and supporting documentation are licensed under a Creatives Commons Attribution Non-Commercial and No-Derivatives 4.0 International license.

Author: Anna Ashenden