Effective ways to support youth into employment

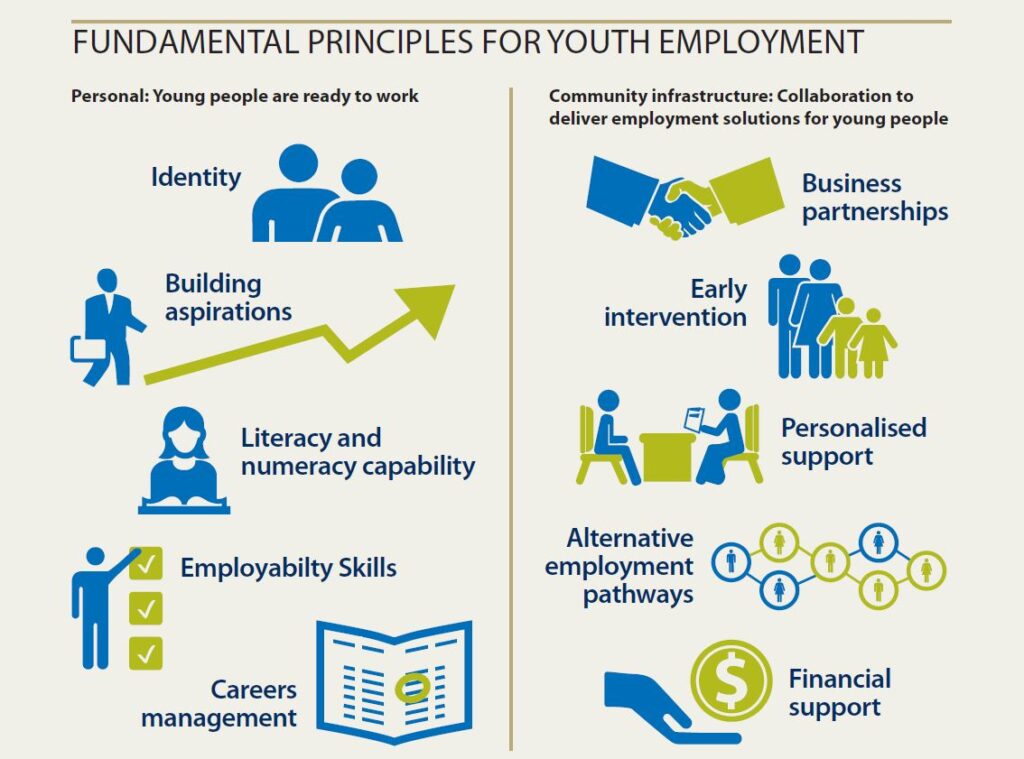

Use these 10 fundamental principles to design and evaluate programs to most effectively counter the persistent problem of youth unemployment.

- Youth unemployment continues to be a persistent problem, reaching 28% in some Australian communities.

- The 10 fundamental principles essential to support at risk young people into employment cover ‘personal’ factors (the capabilities and experiences a young person needs to gain and retain meaningful employment); and ‘community infrastructure’ factors (the ecosystem components required to support successful employment transitions).

- These principles (and associated frameworks) can be used by service providers to help design and evaluate programs; and by funders as a guide for assessing the effectiveness of programs before an investment is made.

Youth unemployment continues to be a persistent problem in Australia (as well as globally), reaching as high as 28 per cent in some Australian communities.[1]

While the negative effects of unemployment impact all young job seekers, the impact is felt most by young people considered at risk of, or already experiencing, long-term unemployment.

In Australia immediately prior to the 2008 global financial crisis, a young person spent on average 13 weeks looking for work and less than 20 per cent of this group were classified as long-term unemployed. By February 2014 this had increased to an average of 29 weeks spent looking for work[2] and over 55 per cent were classified as long-term unemployed. Many of these young people spent up to 52 weeks looking for employment, more than triple the time prior to 2008.[3]

Fundamental principles of successful programs

Numerous organisations are working to support at risk young people to transition from education or unemployment into sustainable work.

So what do successful youth employment programs look like in practice? What are the fundamental principles common to effective programs?

‘To find out, SVA drawing on its experience working in employment researched national and international organisations implementing best practice programs as well as the documented learnings from governments and the social sector internationally. The research, supported by the Collier Charitable Fund, focused on the approaches that were most successful for 15-24 year olds that had been out of employment for 12 months or more. However, it also included successful school to work transitions which support at risk young people. Research results are published in The fundamental principles for youth employment report.

The drivers of unemployment

The research highlighted the underlying drivers or causes of youth unemployment, some of which are felt more strongly by those experiencing multiple barriers. These drivers are classed as structural, societal and personal.

Structurally, the number of appropriate and accessible job vacancies is the most critical factor influencing the number of unemployed young people and the length of time they spend unemployed.[4] However, at a program level, it is difficult to have influence over this level – as it pertains to global, government or institutional structures.

Societal drivers refers to the community within which a young person lives. The prosperity of the community, the educational options available, community organisations, and whether the community is remote, regional or urban are all important. These drivers are heavily influenced by structural factors but are adaptive, flexible and have the potential to be a positive influence for young people.

The personal drivers refer to a young person’s immediate environment: their family, role models and immediate community and tend to shape a young person most strongly.

About the principles

The research identified 10 fundamental principles (see the infographic and Table 1 below). These were mapped into areas relating to the latter two drivers as the successful programs were addressing a defect in one of these.

The principles relate to the personal capabilities and community infrastructure needed to support young people into employment.

Each principle demonstrates the skills and/or supports a young person needs to transition from long-term unemployment into sustainable work.

The ‘community infrastructure principles’ are not co-dependent unlike the ‘personal principles’. Their relevancy is based on an individual’s life stage and the complexity of the barriers the young person is facing. However, they do reinforce one another.

The principles are:

| Personal: Young people are ready to work | |

| Identity | The development of personal identity allows an individual to understand their unique traits and express their interests, beliefs and abilities to themselves and others. |

| Building aspirations | Aspirations are built by an individual having a positive attitude and belief in their own abilities, which is nurtured and developed by those around them. A young person who has strong aspirations is more likely to stay in education and employment after setbacks. |

| Literacy and numeracy | Literacy and numeracy provide a solid foundation for all formal education and training from school through to employment. Modified training, with a focus on developing literacy and numeracy capabilities, can benefit young people to gain qualifications and improve their job readiness. |

| Employability skills | Employability, ‘soft’ or ‘life skills’ are personal attributes or behaviours that are core pre-conditions for gaining and retaining employment. These skills can be categorised under cognitive skills, communication and social skills, and personal characteristics. They are demonstrated through effective teamwork, adaptability, problem solving and the ability to clearly communicate ideas or resolve conflict. |

| Careers management | Career management skills are the necessary mechanics for searching and applying for a job and presenting oneself to potential employers. Possessing these skills allows individuals to successfully transition from education to employment and from one job to the next over the course of a working life. |

| Community Infrastructure: Collaboration to deliver employment solutions for young people | |

| Business partnerships | Effective cross sector partnerships with business can build a young person’s employability skills, meet employers’ recruitment and retention needs and create better employment outcomes for disadvantaged job seekers. |

| Early intervention | Early intervention activities are most effective when they take place in the school environment and are tailored to address the specific needs of the young person. For young people who are already experiencing unemployment, it is critical that intervention takes place swiftly to ensure that the time spent unemployed is as brief as possible. |

| Personalised support | Personalised support is the opportunity to clarify and assess the individual obstacles a young person is facing. A support framework is then designed which addresses those specific barriers and is monitored and adjusted to ensure the best possible outcome. |

| Alternative employment pathways | For a young person unemployed for 12 months or more, having the opportunity to gain experience working in a flexible, supported non-traditional work place such as a social enterprise, intermediary labour market or participating in an employment transition program allows them to build experience, aspirations, confidence, knowledge and skills in a supportive working environment. This has been proven to act as a successful bridge back to the open labour market. |

| Financial support | Financial support provides the economic security necessary for a young person to maintain a basic quality of life (access to food, housing, clothes and public transport) while searching for employment. |

These principles were selected with long-term unemployed young people aged 15-24 front of mind, however the research demonstrated that they are universal and not specific to this cohort. These principles were also proven effective across many different at-risk groups and for those experiencing complex barriers.

At-risk cohorts include young people with a disability, First Australians, those with caring responsibilities, young people from low socio-economic communities, and those who have not completed Year 12. Many of these disadvantaged young people experience individual barriers to employment, such as drug and alcohol abuse, unstable housing or limited access to education or transport.

How to apply the principles in practice

To support the practical application of the principles, a framework for each principle outlines the:

- Activities a young person should be engaging in which will nurture the development of the principle;

- the resourcing and delivery of the principle, including who needs to be administering the activity at different stages of the young persons career journey and how often they should be exposed to the activity; and

- the indicators that would strongly suggest the skills associated with the principle have been developed in the young person.

The frameworks can be used differently according to the stakeholder needs.

Service delivery organisations, employers, education providers and government can use the frameworks to help design and evaluate programs.

Funders including philanthropy, business and government can use the frameworks as a guide for assessing the effectiveness of programs before an investment is made.

An example of the framework for the Building Aspirations Principle is shown in Table 2 below.

| Principles in action: Building aspirations | |

|---|---|

| Activities | Resourcing and delivery |

| 1. Set goals based on values, interests and research | 1. One-off training, revisited as needed. Can be adapted for all ages, beginning at Secondary school and delivered in schools or by social purpose organisations and employment services. |

| 2. Participate in co-designed and delivered education and training curriculum showing relevancy to real life workplaces | 2. On-going – structured courses. Can be adapted for all ages beginning at Kindergarten and delivered in schools, by social purpose organisations or employment services in partnership with employers. |

| 3. Exposure to positive role models (community, education and employer mentors) | 3. One-off and on-going regular mentoring. Can be adapted for all ages beginning at Kindergarten and delivered at school, by social purpose organisations or employment services |

| 4. Participate in leadership and development training | 4. On-going –structured course. Can be adapted for all ages beginning at Junior Secondary School and delivered at school, by social purpose organisations, employment services or employers |

| Indicators | |

| A young person has: – Motivation to seek employment and a positive attitude towards work – Belief and confidence in their ability to achieve goals – Understanding of potential career pathways, individual interests and goals – Ability to set goals and plan for their achievement – Role models championing for and encouraging future success | |

In the report, a related case study accompanies each framework to demonstrate how the principle is used in action. For example, the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME) program (p20 in the report) incorporates the principles of building aspirations as well as identity, literacy and numeracy capabilities, employability skills, careers management, business partnerships, early intervention and personal support.

Applying these principles in the design and funding of programs will ensure the most effective support for at risk young people.

Writer: Justine Little

[1] Queensland – Outback, Jan 2016, Brotherhood of St Laurence, Australia’s Youth Unemployment Hotspots Snapshot, March 2016

[2] ABS, 2014

[3] Borland, 2014

[4] Muir, Powell and Butler, 2015

Read the executive summary Read the full report