Housing First: the challenges of moving from pilot to policy

With a growing body of evidence backing the highly supportive Housing First approach, including the recent evaluation of the Aspire SIB, why has it not been funded and adopted more extensively?

- Housing First is an approach to housing and supporting people experiencing chronic homelessness. Programs applying this approach typically include intensive case management and specialised supports alongside permanent housing.

- Evaluations of programs in Australia as well as internationally have consistently demonstrated the success of the model for people experiencing chronic homelessness as well as for governments through the resulting cost savings.

- Barriers to embedding this approach in the policy and service delivery landscape include the disconnect between the funding of program costs and the resulting savings across government agencies; the complexity of reforming the homelessness service system; and the shortage of social and affordable housing.

Homelessness is a significant and complex issue that is often met with fragmented and inadequate responses. In 2016, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that the population of people experiencing homelessness in Australia was over 116,000, with around 8,200 people sleeping rough on Census night.1 The Covid-19 pandemic catalysed unbudgeted funding for homelessness services from state governments, which mainly consisted of emergency accommodation for rough sleepers.2 Some state governments also funded supports to transition these individuals into longer term housing (for example, Together Home in NSW and From Homelessness to a Home (H2H) in Victoria). However, much more needs to be done to end homelessness in Australia.

There are solutions to addressing and eventually ending homelessness. The Centre for Social Impact put forward five key policy actions in a report released earlier this year. One specific action is the adoption of Housing First supportive models of care, which have increasingly been trialled in Australia. This article looks at what the Housing First approach is, the findings of evaluations of this approach (including outcomes achieved and why this approach works), and then explores why these pilots haven’t yet become standard policy.

Aspire Social Impact Bond

SVA launched the Aspire Social Impact Bond (SIB) in 2017 to make a lasting difference to the lives of people experiencing chronic homelessness in Adelaide. The SIB funds the Aspire program, which provides long-term case management support grounded on a Housing First approach. Aspire is delivered by Hutt St Centre, an Adelaide based homelessness services specialist, in partnership with public and community housing providers. Since inception, almost 600 people have enrolled in the program and been supported for up to three years. The program has recently been independently evaluated, highlighting the positive outcomes it has generated and the key factors underpinning the Aspire SIB’s success.

Housing First

Housing First is an approach to housing and supporting people experiencing chronic homelessness. Programs adopting Housing First approaches typically include intensive case management and specialised supports alongside permanent housing.

Housing First as an approach has been relatively well known and understood for some time, with the approach first being recognised in the USA in the 1990s and many advocates in Australia calling for the adoption of the approach since the late 2000s.3

A set of Housing First Principles for Australia have been developed to support the adoption of the model across the country, which include:

- people have a right to a home

- housing and support are separated

- flexible support for as long as it is needed

- choice and self-determination

- active engagement without coercion and

- social and community inclusion.

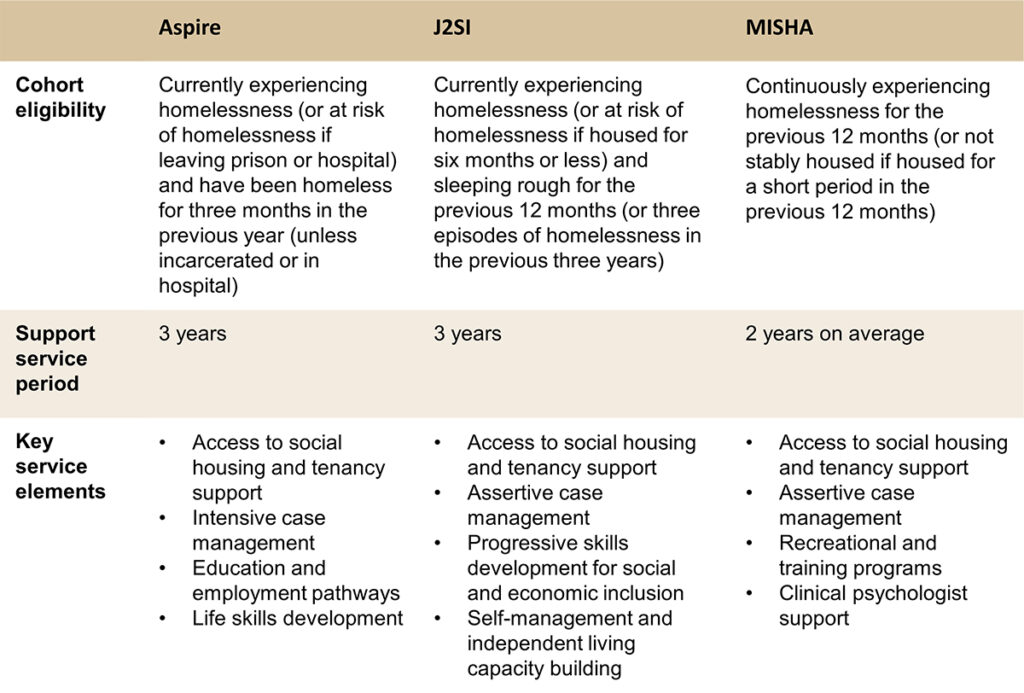

Over the past 15 years, the prevalence of programs adopting Housing First principles has grown in Australia. These include Sacred Heart Mission’s Journey to Social Inclusion (J2SI) program, Mission Australia’s MISHA Project, various Common Grounds across Australia as well as the Aspire program. As outlined in the table below, these programs support slightly differing cohorts, and deliver services in slightly different ways, but they share Housing First DNA. There are other similar programs across Australia, which are not explored in this article.

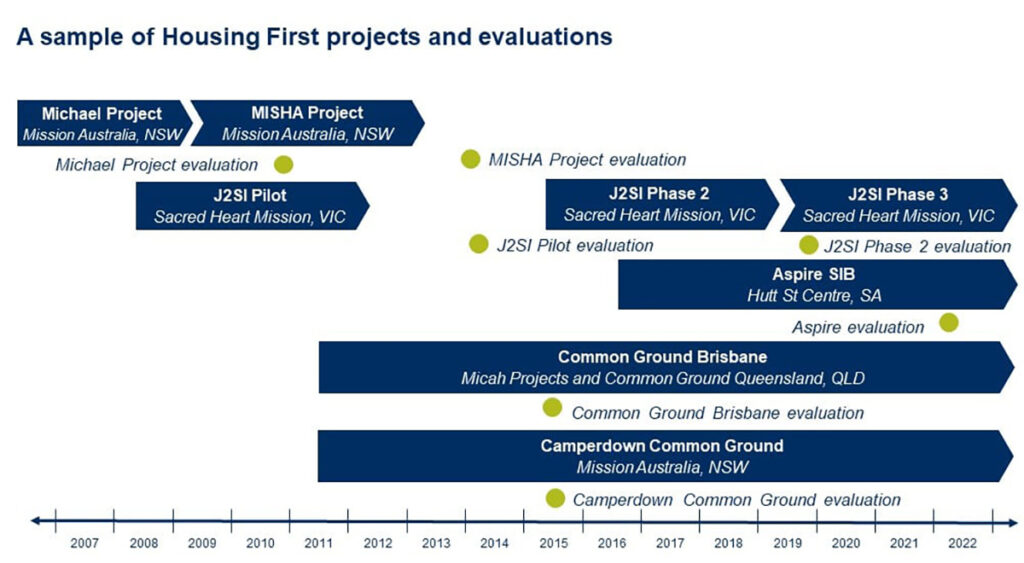

Despite each of these programs being time-limited, relatively small-scale projects, most have been evaluated, leading to a welcome growth in the evidence base underpinning Housing First approaches in the domestic context. The adoption of the model under a number of social impact bonds both domestically and overseas (such as the Aspire SIB and the Denver Supported Housing Social Impact Bond (Denver SH SIB) initiative in Colorado, USA) has helped to create robust and publicly accessible outcome data.

The results

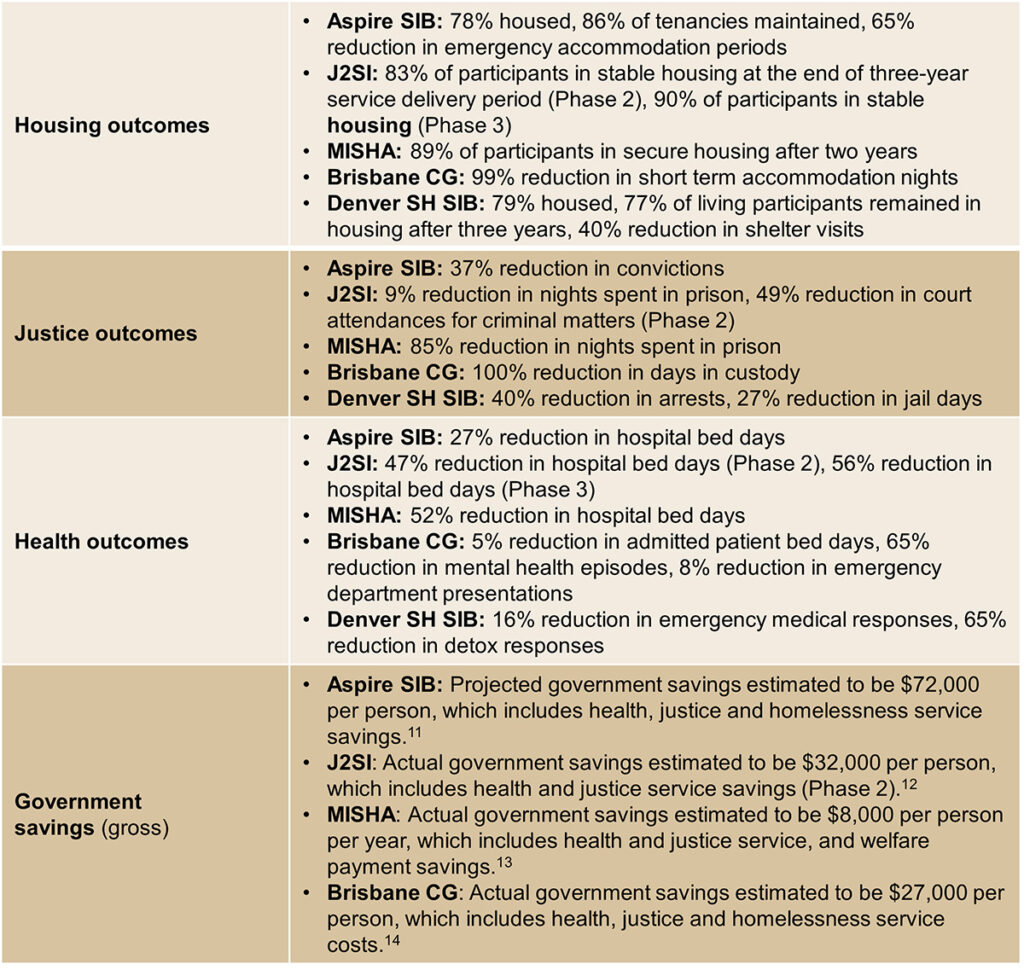

Evaluations of programs adopting Housing First approaches have consistently demonstrated the success of the model for people experiencing chronic homelessness (and for governments): high engagement, relatively high housing placement rates, high housing retention rates, improvements in wellbeing, high engagement with employment and community, and reductions in health, justice and homelessness service use.

A sample of the outcomes achieved is summarised in the table below. It should be noted that each program utilises different outcome metric definitions, counterfactual or baseline methodologies, data sources, measurement period and calculation approaches. Refer to the evaluation reports and other publications for further details (Aspire SIB4,5, J2SI6,7, MISHA8, Brisbane Common Ground (Brisbane CG),9 Denver SH SIB10).

Why it works

As highlighted by the Aspire SIB evaluation, three fundamental – and quite straightforward – factors underly the success of Housing First models:

- Access to housing: Housing provides the platform for life changes and improvements in health and wellbeing, and the capacity to help individuals secure and maintain permanent housing is intentionally factored into the program design. Although housing is fundamental to a Housing First model, it can also be a limiting factor, as sourcing housing may not be entirely within the control of the organisation delivering the program. Aspire relied on a combination of public and community housing allocations for participants, which prevented a rapid rehousing approach but did successfully secure long-term housing for 78% of all individuals enrolled.15 Capacity to match individuals to appropriate housing and a focus on providing individuals with a choice of location and property where possible increases the likelihood that an individual maintains their tenancy.

- Length of support: Support to help an individual meet their needs, aspirations and goals is provided for an extended period of time. This accommodates individuals’ non-linear recovery pathways and variation in engagement with the program over time and recognises that complex challenges take time to address. Support was provided for up to three years in the case of the Aspire program, with the most critical period usually the first 12 months. After this, and particularly once housed, individual’s reliance on support gradually reduced. It is important that individuals know the support is available to them, whether they experience a setback or success. Not all individuals require the full three years of support; some may require longer, lighter touch, support.

Knowing that you’ve got support for three years makes a major difference. I can’t stress it enough, how comfortable they make you feel, it’s a whole non-judgemental thing. Aspire has helped me gain the confidence to tell the truth, I can be honest with people.”Aspire participant

- Intensity of support: Enabled by low caseloads, intensive supports are offered to individuals with complex needs. Case workers are able to dedicate considerable time and energy to individuals and tailor their support to the specific goals and needs of each individual, enabling the development of deep, long-term relationships. This builds trust, respect, makes individuals feel genuinely cared for and allows case workers to be ‘relentless‘ with their approach and tailor it to individuals’ needs. The target case load ratio for Aspire was one case worker to every 15 participants (much lower in the first year, and higher in the third), with engagement navigators providing support to help participation in community activities, training and employment opportunities. Similarly, the J2SI Phase 3 target caseloads are 6 in the first and second years of support and 10 in the third year, and the Denver SH SIB caseload was 13 on average.

They went above and beyond for me … without them I wouldn’t be here at all… they’ve been absolutely invaluable to my mental health, my emotional health and my stability in the house.”Aspire participant

So why isn’t this approach embedded within the policy and service delivery landscape?

Although the case for the Housing First approach is evident and there is an unmet need, there are several barriers to governments funding, and the sector adopting, this model more broadly across Australia. It should be noted that some of these challenges are not unique to the Housing First approach – there are many support models with a strong evidence base facing similar challenges in moving from pilot to policy.

1. Disconnected costs and benefits

The effects of homelessness pervade multiple government agencies, including health, justice, housing, child protection and social services. While homelessness services are typically funded by housing or community services agencies, evaluations demonstrate that the greatest proportion of benefits accrue to health and justice agencies. Over the four years to 30 June 2021, the Aspire program generated savings of $13.4 million to the South Australian Government,16 of which 51% related to health services, 40% related to justice services and 9% related to homelessness services.

There is a clear misalignment between the ‘cost centres’ and the ‘savings centres’ for homelessness services, making it difficult for a government housing agency alone to build the economic proposition that a Housing First initiative stacks up. State government initiatives such as the Victorian Government’s [Early Intervention Investment Framework] could help to address this difficulty.

This misalignment is particularly challenging as, relative to the crisis care-oriented model that is prevalent in the system, Housing First programs are ‘expensive’ due to the success factors identified above – long-term support, skilled and deeply passionate staff with low case loads, and dedicated housing. For example:

- Aspire SIB: the cost to deliver the intensive case management support over three years is $18,000 per person.17 This does not take into account the average cost of providing social housing in South Australia per year which is $14,000 per public housing dwelling18 and $9,000 per community housing tenancy rental unit.19

- J2SI Phase 2: the cost to deliver the intensive case management support (excluding the provision of housing) over three years was $64,000 per person.20

- MISHA: the cost of support (excluding the provision of housing) was $28,000 per client over two years.21

In the absence of readily accessible comparative savings figures, and despite the social benefit to the individual and community, support of this nature can appear costly rather than good value.

2. Complexity of reforming the homelessness service system

Existing homelessness service systems are complex, encompassing a range of services, providers and funding models – in FY2020 alone the Victorian Government spent $383m on homelessness services across 635 providers and the New South Wales Government spent $259m across 335 providers.22 Systems of this scale are very difficult to reform because:

- Systems with large numbers of providers and services are built on efficiency, with highly standardised procurement processes, contracts and pricing – any changes create bespoke processes and arrangements, reducing the level of standardisation and potentially compromising efficiency.

- Existing providers have built their business models and services around existing homelessness services funding – any changes to the system means disrupting these providers and their established funding lines.

- There are limited incentives in the system to innovate, do things a better way and go through the pain of changing – any change has an associated transition cost that comes with it.

- Procurement cycles are long and rigid, preventing continuous improvement through the adoption of new practices as new evidence comes to light – any change must wait until the next procurement cycle.

- Homelessness service systems assist many sub-cohorts within the broader population of people experiencing homelessness – any change needs to ensure that there is clear understanding of what interventions work for who (and what doesn’t work for who).

These are significant barriers to reform and to determining how to permanently integrate a Housing First model into existing systems. A suggested starting point for government is to undertake a planning process incorporating the steps set out below.

Sizing the need

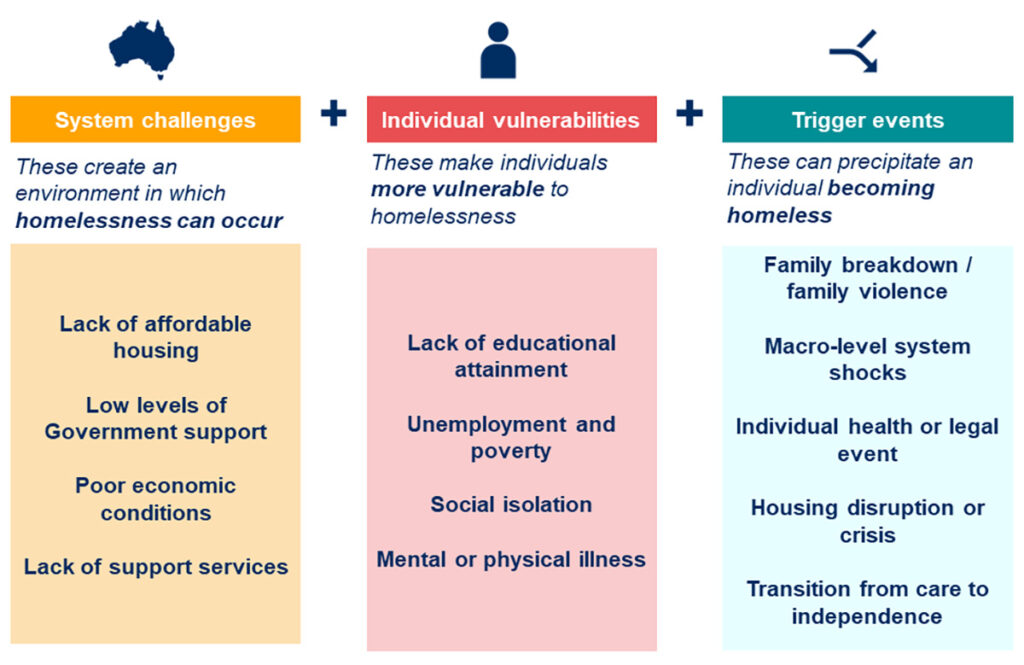

The first step is having a clear understanding of the drivers of homelessness. The pathways into homelessness are complex and personally unique, but there are recurring causal themes. Homelessness often arises from a confluence of vulnerabilities and/or events for individuals. These vulnerabilities and events can be characterised as system challenges, individual vulnerabilities, and trigger events as outlined below.

While 116,000 people were estimated to be experiencing homelessness in Australia in 2016, not all of those 116,000 individuals required just a house; not all required a crisis response; and not all required three years of intensive case management support.

The NSW Government recently commissioned a Taylor Fry analysis to identify risk factors that will support the early identification of different groups at risk of homelessness. Different groups within the homeless population have different needs requiring different service responses (although there is overlap). The Aspire evaluation indicated that it was an effective intervention for people with complex needs, notably mental health issues, disability and problematic drug and alcohol use, and/or experiencing chronic or recurrent homelessness.

The next step is sizing the cohort within the broader homeless population who have a need which could be met through a Housing First approach (i.e. the provision of both no-strings-attached housing and long-term support).

Implementation design

Governments then need to decide how they will implement the Housing First program. Options may include:

- Expand specialist homelessness services – funding to specialist homelessness service (SHS) providers could be expanded to deliver a Housing First based service in addition to other homelessness services. SHS providers collectively receive over $1 billion from state and territory governments each year to deliver primarily short-term and crisis-orientated services. There is a high degree of standardisation in contracts, procurement processes and program guidelines, meaning changes may be difficult to impose and maintain over time.

- Community housing – funding to community housing providers (CHPs) could be expanded to procure specialist homelessness services to deliver case management support to a targeted cohort of their clients. The NSW Government used this approach in the delivery of its Together Home Program in 2020, by leveraging its Community Housing Leasing Program funding mechanism and contracts. Additional funds were allocated to CHPs to provide housing (via headlease or owned stock) and engage providers to deliver wraparound supports. Challenges with this option arise if CHPs are not resourced to procure support services, and service providers are not funded for full FTE roles (making it difficult to build stable and capable teams). There is likely to be a high level of variability in service models if there are many CHPs commissioning services.

- Stand-alone program – governments could establish and tender out new programs to fund and oversee the integrated delivery of a Housing First initiative. This would enable strong oversight of the program but could be somewhat disconnected from ‘BAU’ homelessness and CHP services.

Transition

With a broader roll out of a Housing First program, the following need to be considered:

- Sector transition – most homelessness service providers are charities, which do not have idle cash to fund the cost associated with any disruption to their business model and services. Funding needs to be made available to support service providers with the transition.

- Sector capability – services are typically structured around government funding. The capabilities within the organisation are then aligned to deliver those services. As there is a limited number of providers who have delivered intensive Housing First models, time is needed to implement the capabilities and capacity to deliver these services (recruit staff, train staff, develop practice materials). There are some resources available to support this (J2SI licensing and support, AHURI Common Ground Housing Model Practice Manual).

- Client transition – current arrangements largely fund relatively low intensity services for a high volume of clients. The creation of high intensity/long duration services should reduce the need for crisis support, but this would not occur immediately, requiring overlapping funding. New triage and referral pathways would also be required within the system to ensure individuals receive the type of support appropriate to their needs.

- Embedding core outcome metrics – government and service providers need to agree on the right outcome metrics and performance targets to ensure that the impact of the Housing First model is demonstrated over time, ensuring that it survives procurement and political cycles.

3. Shortage of social and affordable housing

As highlighted by the Aspire evaluation, the shortage of social housing and affordable private rentals is a key limitation to delivering the permanent housing element of the Housing First model. Under-investment in social housing in recent decades has been well documented, with the number of social housing households growing by 3% over the decade to 2020 while the Australian population grew by 15%. At the same time, demand for social housing has grown with the decline in housing affordability. The number of people on the social housing waiting list at the end of FY2020 was 166,000, with around 63,000 being considered high needs.23 Without significant investment in new social housing stock, allocations rely largely on turnover in properties.

Housing First programs have had to rely on a range of sources and methods for securing housing in the absence of new social housing stock. Each source has its own limitations in that it either prioritises one group over another or defers the challenge of securing long-term housing:

- Agreement from CHPs to prioritise housing – Aspire intended to secure a minimum number of properties from CHPs for program participants. However, the intended level of supply was not met with only 23% of participants being placed in community housing.24

- Priority allocation from social housing register – Aspire has had to primarily rely on priority allocations of scattered site public housing from the public housing register to meet its housing requirements. 54% of Aspire participants have been placed in public housing.25 Housing has not always been timely, with Aspire participants waiting 180 days on average to be placed in a new home.26 In Victoria, the average wait time for being allocated social housing is around 12 months from the date of being approved as a priority applicant.27

- Headlease properties from the private market – some programs (including J2SI Phase 3, Together Home and H2H) have utilised a head leasing model, whereby CHPs lease properties from the private market and sub-lease them to program participants. This model requires a dedicated housing subsidy to cover the shortfall in market rent paid by CHPs, being the difference between the market rent and the tenant contribution (25% of income plus Commonwealth Rent Assistance). This housing is technically not permanent housing and arguably defers the housing problem until a later date. Under the head leasing model, housing is funded for a fixed period, with the intention of transitioning the program participant into longer-term housing (generally when social housing becomes available via the housing register or the individual has sufficient income to take over the headlease). With current rental rates, it is difficult to source properties which individuals could realistically rent privately if they were to take over the headlease.

- Affordable private rentals – this housing option is considered suitable for a small proportion of people who have experienced chronic homelessness. This is highlighted by the low number of private rental housing outcomes for Aspire and J2SI, with only 2% of Aspire participants28 and 8% of J2SI Phase 2 participants29 securing housing in private rentals. There are various government services and subsidies to support people into private rentals, but without a downward shift in rental rates or an increase in rent subsidies, this may not be a long-term solution.

The purchase or build of new housing stock has been possible for some Housing First programs. Common Ground models that provide congregate or apartment-style affordable housing alongside tailored support services delivered onsite have generally secured funding for land purchase and construction (or acquisition of stock) via a combination of Commonwealth Government, state government, local government and private sources.30 The Denver SH SIB in the USA used an innovative tax incentive scheme to fund the build of a single-site building with onsite services to units, which provided 66% of houses for program participants.

In the absence of increasing the pool of available social housing, suitability of housing becomes an increasing challenge, as does the risk of concentrating disadvantage in areas and developments with higher levels of social housing.

There is a clear evidence base for the highly supportive Housing First model. State and territory governments have the opportunity to think through how to bring together funding across multiple government departments and embed the model within the service system, planning for and managing system disruption.

The Housing First model makes a demonstrable difference in people’s lives and delivers benefits to government budgets.

Whatever path governments take, there remains a need to instil a rigorous outcomes measurement methodology within the programs, as deployed in social impact bonds and other outcomes-based funding models (without necessarily attaching payments to outcomes). This would ensure that the impact of the model is consistently demonstrated over time, creating resilience over the terms and budget cycles of government. Some of the barriers to system reform are not unique to Housing First, as there are many intervention models with strong evidence bases struggling to transition from pilot projects to policy.

With access to permanent housing also being critical to the success of the Housing First model, a new National Housing and Homelessness Agreement / Strategy is also required which commits the Commonwealth Government to significantly increasing the supply of social and affordable housing and increasing Commonwealth Rent Assistance rates.

The Housing First model makes a demonstrable difference in people’s lives and delivers benefits to government budgets. If governments adopt a ‘whatever it takes’ approach to overcome the barriers to reform and the housing crisis – which we have seen is possible over the past few years – then Housing First can start the worthwhile journey from pilot to policy.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness 2016.

- Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), Australia’s COVID-19 pandemic housing policy responses, AHURI Final Report No. 376, 2022.

- AHURI, Policy shift or program drift? Implementing Housing First in Australia, 2012.

- Coram, V., Lester, L., Tually, S., Kyron, M., McKinley, K., Flatau, P. and Goodwin-Smith, I. Evaluation of the Aspire Social Impact Bond: Final Report, Centre for Social Impact, Flinders University, Adelaide and Centre for Social Impact, University of Western Australia, Perth, 2022.

- Social Ventures Australia, Aspire Social Impact Bond: annual investor report 2021.

- A., Callis, Z., Thielking, M., & Flatau, P. Chronic Homelessness in Melbourne: Third Year Outcomes of Journey to Social Inclusion Phase 2 Study Participants, Sacred Heart Mission, 2020.

- Sacred Heath Mission, Journey to Social Inclusion program outperforms its targets, 2021.

- Conroy, E., Bower, M., Flatau, P., Zaretzky, K., Eardley, T., & Burns, L. The MISHA Project: From Homelessness to Sustained Housing 2010-2013, 2014.

- Cameron Parsell, Maree Petersen, Ornella Moutou, Dennis P Culhane, et al.. Brisbane Common Ground Evaluation: Final Report, 2015.

- 10 Urban Institute, Breaking the Homelessness-Jail Cycle with Housing First: Results from the Denver Supportive Housing Social Impact Bond Initiative, 2021.

- Aspire SIB financial model (as at 30 June 2022); actual and projected savings over 3-year measurement period estimated at $27,000 per person; allowance for discounted future savings totalling $45,000 per person.

- Chronic Homelessness in Melbourne: Third Year Outcomes of Journey to Social Inclusion Phase 2 Study Participants, 2020; actual savings for J2SI intervention group over 3 year period estimated at $32,000 per person.

- The MISHA Project: From Homelessness to Sustained Housing 2010-2013, 2014: actual health, justice and welfare service savings described on a per person per year basis.

- Brisbane Common Ground Evaluation: Final Report, 2015: actual savings over 1 year period estimated at $27,429 per participant.

- Operational data as at 30 June 2022

- $8.9m relates to savings arising in the measurement period, with a further $4.5m attributed to future avoided services for individuals who have completed their support period.

- Aspire SIB financial model (as at 30 June 2022)

- Report on Government Services 2021, 18 Housing, Table 18A.43, Government recurrent expenditure per dwelling, public housing, 2019-20 dollars.

- Report on Government Services 2021, 18 Housing, Table 18A.45, Government recurrent expenditure per tenancy rental unit, community housing, 2019-20 dollars.

- J2SI Phase 2 Final Year Outcomes Quantitative Report, Table 5, 2020.

- Conroy, E., Bower, M., Flatau, P., Zaretzky, K., Eardley, T., & Burns, L. The MISHA Project: From Homelessness to Sustained Housing 2010-2013, 2014.

- Report on Government Services 2021, 19A Homelessness Services, Table 19A.1.

- High needs, as determined by Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, means occupants of the household were subject to one or more of the following circumstances: they were homeless, their life or safety was at risk in their accommodation, their health condition was aggravated by their housing, their housing was inappropriate to their needs or they had very high rental housing costs.

- Operational data as at 30 June 2022

- Operational data as at 30 June 2022

- Evaluation of the Aspire Social Impact Bond: Final Report, (7.1.4 Summarising Housing Outcomes), 2022

- Victorian Government, Social Housing Allocations 2019/2020.

- Operational data as at 30 June 2022

- J2SI Phase 2 Final Year Outcomes Quantitative Report, Table 5, 2020.

- For example, for the Brisbane Common Ground, the Commonwealth Government provided the major portion of funding for land and construction under the Nation Building Economic Stimulus Plan and the Queensland Government provided some funding for construction works.