How to adopt an outcomes-focused approach

This step-by-step guide for setting up an outcomes management approach is drawn from Managing to Outcomes: A guide to developing an outcomes focus. Part one covers defining how you create the change.

The social sector is increasingly becoming focused on outcomes. Government departments, philanthropists and consumers of social services are encouraging a shift towards an outcomes-focused approach. Service providers are responding in a range of ways to help them secure funding, or to help them improve their capacity to achieve positive changes for their stakeholders.

Outcomes are the positive changes that happen for people as a consequence of an activity – doing something. For example, the activity of giving a child a pair of glasses leads to the outcomes of a child being able to see; and the child being able to read in class and gain confidence.

Outcomes-focused management approach

Adopting an outcomes-focused approach means orienting your organisation to achieve outcomes – the results of your activities. A focus on outcomes helps organisations prove to stakeholders that what they are doing is working. More importantly, it also helps organisations improve what they are doing, by being armed with better information about what is working and what is not.

This two-part article builds on the SVA Quarterly article [‘Managing to outcomes: what, why and how’] by concentrating on the ‘how’ and describing the main tasks: developing a ‘logic model’ (also known as a theory of change or a program logic) and measuring outcomes.

The content for this article is drawn from Managing to Outcomes: A guide to developing an outcomes focus, a clear step-by-step guide to adopting an outcomes-focused approach. SVA developed this guide after working with the NSW Social Innovation and Productivity Council to support the human services sector to adopt an outcomes-focused approach.

Define how you are creating change

The first step to adopting an outcomes-focused approach is understanding what outcomes your organisation is trying to achieve – to answer ‘Why are we doing this?’

Your organisation needs to be clear about what it is trying to achieve. Specifically, what are the changes (i.e. the outcomes) that you want for the people you work with, and how your activities lead to that change?

A logic model is one tool that can help to clearly tell the story of how your activities work. Described most simply, the logic model is a statement of intended consequence (i.e. if we do these things, then we will achieve these things). For example, if we provide services to older people in their homes, then we will prevent premature or unnecessary residential care. If we provide housing services to homeless people, then we will reduce homelessness.

A logic model can support evidence-based decision-making about the best way to address an issue.”

A logic model is a common way of defining, and visually representing, the outcomes that will happen as a consequence of your activities. The model identifies the intended causal links between the activities and the short, medium and long-term outcomes. The various elements, and the causal links shown between them, articulate your theory of how change will happen. Once you have developed a logic model, you should gather evidence by measuring and analysing data to test that your theory works in practice, and what, if anything, needs to change to achieve the desired impact.

A logic model can support evidence-based decision-making about the best way to address an issue. It can be used to describe the theory of how change will happen for one program, a group of programs, or an entire agency or non-government organisation. Logic models can also be used to represent your theory of how to respond to a particular issue, or how to support a particular cohort.

There is no ‘one way’ to represent a logic model – the test is whether it is a logical representation of the program’s causal links.

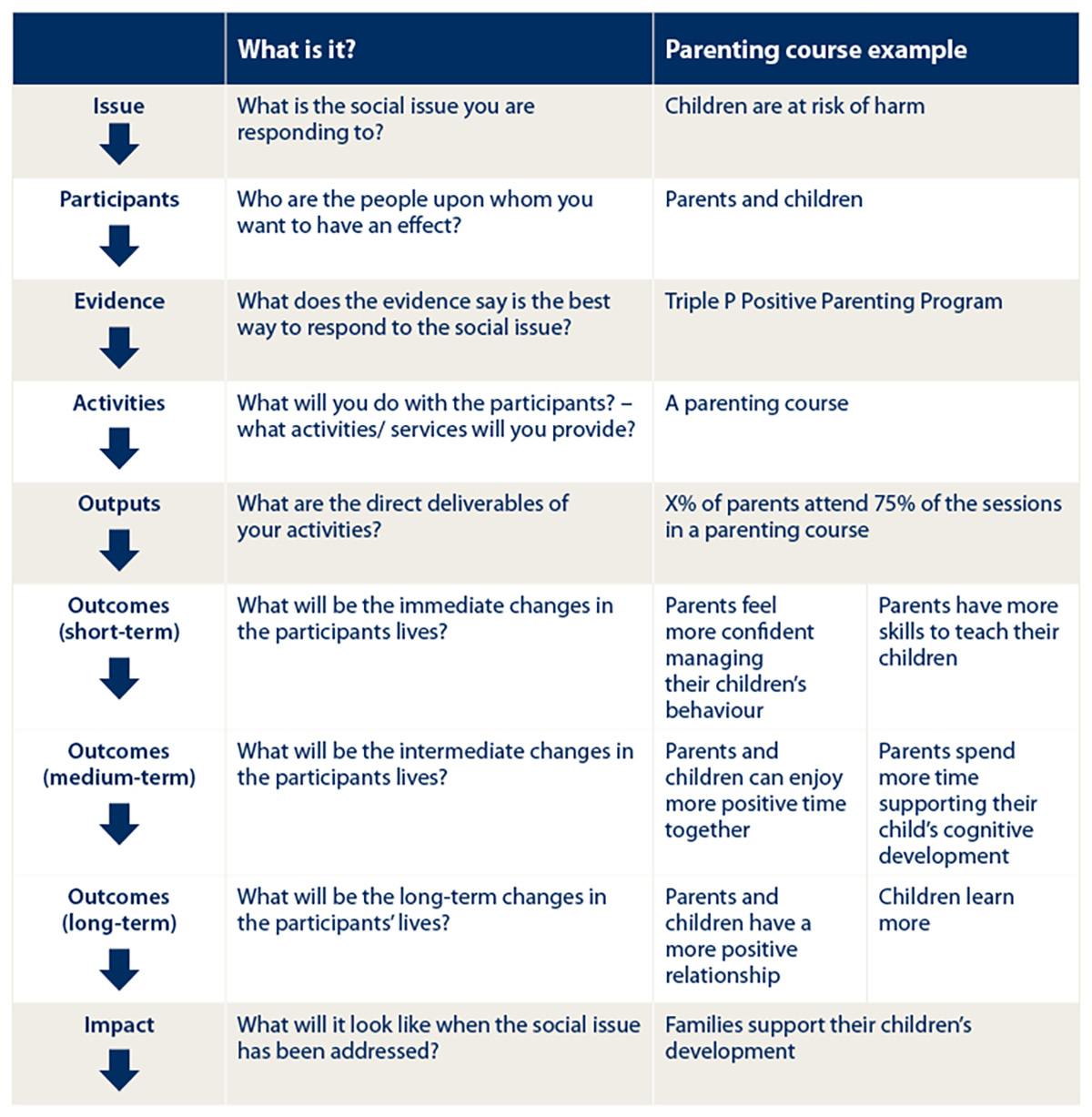

Below is an example logic model for a parenting program. We will discuss each of the headings of the logic model chain so you can better understand how you could use those same headings to build a logic model for your own programs.

Define the issue

It is important to clearly define the issue you are trying to address even if you have been working on the issue for many years.

In the case of a parenting program, the issue could be x% children from disadvantaged backgrounds in NSW are not school-ready at five years old.

A valuable source of information about what the issue is, and how that issue effects people’s lives, are the people who are experiencing the issue. Stakeholder consultation is important to gain valuable insights into what the real problem is that you are trying to solve. For example, interviewing a person who is homeless might reveal that the real issue for that person is not a lack of finances, but rather mental health issues.

Action: To understand your issue better, speak to stakeholders and program staff.

You can begin to build your logic model by writing a concise (fewer than three sentences) description of the issue your program is trying to achieve.

Define the participants

Who are the people upon whom you want to have an effect?

For example with the parenting program, participants would be children from disadvantaged backgrounds under five years old in NSW.

You should be able to clearly identify who your participants are. This includes all those who will benefit from any strategies or activities, including people with a need or aspiration to change something in their lives..

You might ask the question, where do we draw the line? Your program arguably touches so many people’s lives; you should only include stakeholders who will be effected by the program in a material way. For example, stakeholders might include people receiving services, those people’s immediate family and carers if they are significantly impacted by a change in that person and funders and staff of the service.

Action: List all the material stakeholder groups. Be specific and include the number of participants and the geographical area that those participants are in.

Gather evidence

What does the evidence say is the best way to respond to the social issue?

For example with the parenting program, what’s the evidence about childhood development goals, about attachment theory?

You can use evidence gathered about the issue and about what others have found to work when addressing your issue. This evidence can help to inform initial program design or refinement of an approach. It can be used in consultation with participants and inform co-design activities. Evidence can include published research or systematic reviews of available literature.

You can also gather evidence to better understand the broader issue. For example, evidence can help you to understand the many interconnected factors that lead to a child being school-ready.

Do not get stuck at this point if you cannot find very strong evidence – the best available evidence is still useful and later on, it will be supported by evidence you create through measuring your own activities and their outcomes.

Action: Record the evidence you are relying on. Which evidence suggests that your activity is a useful response to the issue? Is there any evidence that suggests otherwise? Include specific sources.

Describe the activities

What will you do with the participants? – What activities or services will you provide?

Activities are the actions you take to respond to the identified social issue. For example, with the parenting program, the activities could be a parenting course teaching parents how to discipline and encourage children, understand the needs of their children, and be educators.

For another organisation, activities might include running an early child care centre, providing housing assistance or offering counselling for victims of crime.

A logic model can articulate the change that you want to see for just one activity or for a grouping of activities. You can choose how broad or narrow you want to go depending on the level at which you want to be able to observe change. For example, running a school is an overarching activity that consists of many smaller activities, and a reading recovery program is a narrower activity.

Alternatively, you can use a logic model to represent your theory of how change can occur for a particular issue. In that case, you could include all the activities that a range of organisations are delivering to address that issue. For example, if you used a logic model to represent how change can occur when addressing the issue of childhood obesity, you might include as activities:

- child education and exercise (education)

- diagnosis, meal planning, surgery (health)

- parenting programs (social services).

At this point, it is also important to record the inputs you will use to deliver the activity. Inputs are defined as resources that are used by an activity such as money, staff, time, facilities and equipment.

Action: List all the activities, and the relevant inputs, you want in your logic model.

Identify the outputs

What are the direct deliverables of your activities such as the number of people served, or the number of activities/services carried out.

Outputs are the things that happen when you run an activity, but not necessarily changes for people. For example, with the parenting program, this could be 100 parents attend 10 sessions of the parenting course over a three-month period.

In other examples: 20,000 children attended four or more after-school care sessions, 38,000 arthroplasty of knee procedures were performed, 10,000 offenders attended facilitated offender behaviour change programs.

When describing outputs, you do not need to describe the change you hope to see as a consequence of the activity. Those changes are the outcomes.

Action: List all of the outputs that will happen because of the activity within a prescribed time frame (usually a year)

Identify the outcomes

The hard work begins when it comes to articulating the consequences of what you do – the changes that happen for people. Remember that the changes that happen because of your activities are the outcomes. They are the short, medium and long-term changes in people’s lives.

For example with the parenting program, the short-term outcome may be parents feel more confident in their parenting skills, and report greater involvement in their child’s development. The medium-term change: more children attend early childhood education, and achieve development goals, and family relationships are strengthened. The long-term outcome could be more children are school ready, and have a stronger support network, and children are more resilient.

There are four general principles to bear in mind when identifying outcomes.

- Engage your staff and beneficiaries either in the initial identification of outcomes, or while testing or refining them.

- Consequences don’t happen all at once. The immediate consequences may be termed the ‘outputs’ or ‘direct deliverables’ of the program; these are generally what workers are directly involved in securing. The short, medium and longer-term consequences can be termed ‘outcomes’.

- Consequences can be positive or negative, or both. For example, an unemployed young person supported to attend work-readiness training might experience greater levels of stress or anxiety. Being open to identifying both positive and negative consequences is crucial to ensuring the integrity of the resulting program logic statement.

- Be exhaustive. It is important to identify as many consequences that arise from the program as possible, including those which are indirect or seemingly tangential. This is because the program logic is distilled from this ‘universe’ of consequences, so taking a comprehensive approach is most likely to yield a sound logic statement that does not overlook anything. An exhaustive list of outcomes will contemplate outcomes for all stakeholders. Once you have created an exhaustive list, you can identify the core outcomes, without which your participants will not achieve long-term impact. Those core outcomes are your priority outcomes, and the ones you will measure.

Identifying the outcomes for a program is one of the most important, and in some ways one of the most challenging parts of adopting an outcomes-focused approach. Remember:

- Identifying your outcomes is both challenging and rewarding. It can energise and engage employees once they can see that the work they are doing is leading to tangible change for the people they are working for.

- You don’t have to get it right the first time. Understanding change is an iterative process and as you gather information about what works, you can evolve your outcomes.

Action: With these four principles in mind, we suggest holding a logic model workshop to identify, group and order your outcomes. See below for a simple logic model workshop guide.

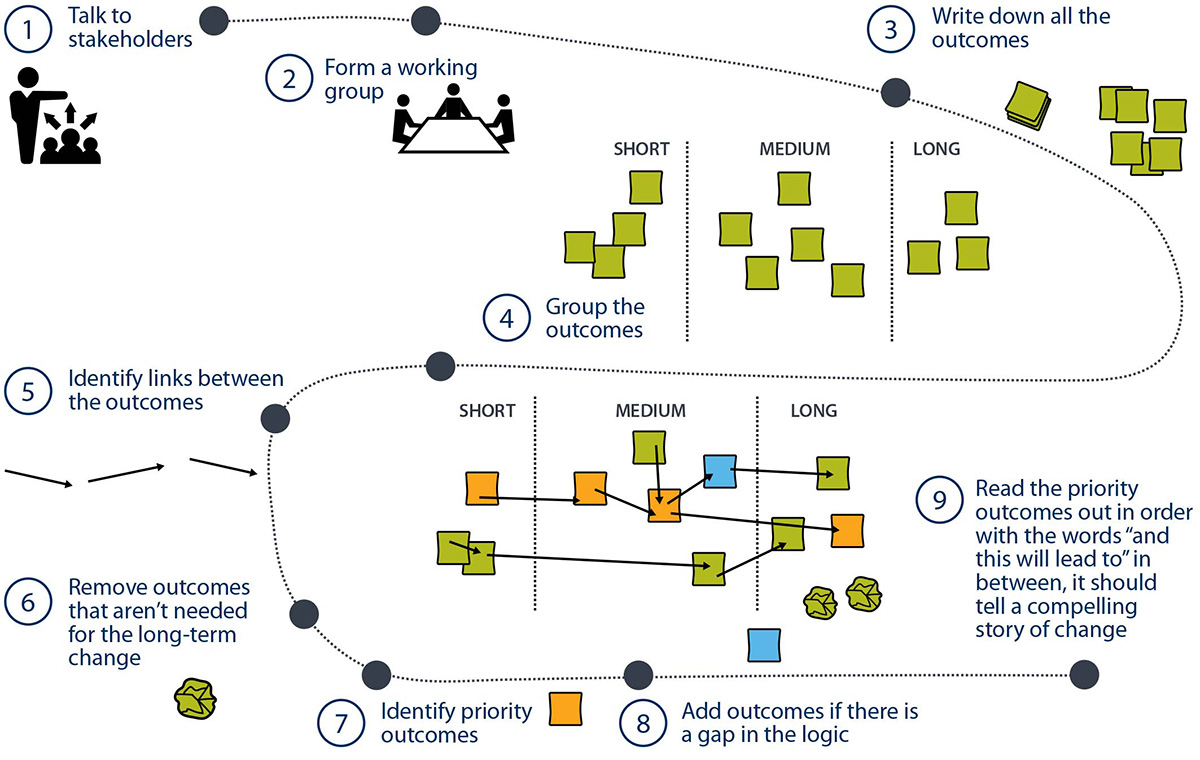

Step one

Talk to stakeholders and program staff to understand the issue and what changes for people because of your activities (i.e. what your outcomes are).

Step two

Form a working group with the people who have spoken to stakeholders, with program staff and with management.

Step three

With your working group, write down all the outcomes that might happen because of your activity. Draw on what staff or stakeholders told you and evidence from activities run elsewhere. Include the long-term changes you hope to see for people as a consequence of your work. The outcomes should be as specific as possible as they will form the basis of what you will measure. Outcomes might start with words like improve, decrease, develop, expand or increase.

Step four

Arrange all the post-it notes on a big table or wall in the order that they happen for people. Try to identify which of the outcomes are short-term outcomes, which are medium-term outcomes, and which are long-term outcomes. You can move the post-it-notes so that they are grouped into short, medium and long-term clusters.

Step five

Try to draw links between the changes, indicating when one change leads to another. Use a pen, draw arrows, challenge the logic – this stage of the process does not have to be orderly or pretty. You can read our article Finding the golden thread for more details on how to prioritise key outcomes.

Step six

You can remove the outcomes that are not leading to any longer-term change for individuals.

Step seven

Take a step back and observe the story as a whole. See if you can identify the really vital outcomes, without which participants in the program will not be able to achieve meaningful change. These are your priority outcomes – they are the ones you should measure.

Step eight

If there is a gap in the logic between the changes that will happen as a consequence of your program, and one or more of the long-term outcomes you hope to see for people, you can add outcomes to describe the changes that you think are needed to get someone to bridge that gap. Other services might achieve those outcomes.

Step nine

Finally, if you read the priorities in order with the words ‘and this leads to’ in between, it should tell a compelling story of change.

Define the impact

What is the ultimate change you want to see happen for people? The impact is often the inverse of the issue you are trying to address. Importantly the way it is described needs to be tailored to the language that stakeholders use to describe the change they want to achieve.

In the parenting example, it would be children from disadvantaged backgrounds have greater ability to learn, contribute and achieve.

Activity: Write down the impact your program hopes to achieve.

Challenge: Now that you have defined your impact, review your logic model. Write down all of the components of the logic model in one place, such as in the table above replacing the parenting example with your program. Work backwards (or upwards) from your impact and challenge yourselves by considering whether you could deliver your activities differently, or deliver different activities, to achieve your impact more effectively.

What will this achieve?

Working through all of these steps will help you to capture in one place the story of the change you want to see as a result of what you do. Logic models are helping service providers to tell their story of change to funders and other stakeholders. Importantly, they are also being used to help organisations to test whether what they are doing is achieving impact.

Organisations can use it as the basis for measuring what they are doing to test their logic and to improve what they are doing to have maximum impact. To take the next step on this journey, see Part two: [How to measure outcomes], or read our full guide [Managing to Outcomes: A guide to developing an outcomes focus], a clear step-by-step guide to adopting an outcomes-focused approach.

Author: Clemmie Baker