Improving outcomes for people with disability

Why the voice and participation of people with disability is a key driver in improving outcomes.

- Almost 20% of Australians (~4.3 million people) experience disability. People with disability tend to be excluded and have poorer outcomes across areas such as education, employment, housing, and health and wellbeing when compared to other members of society.

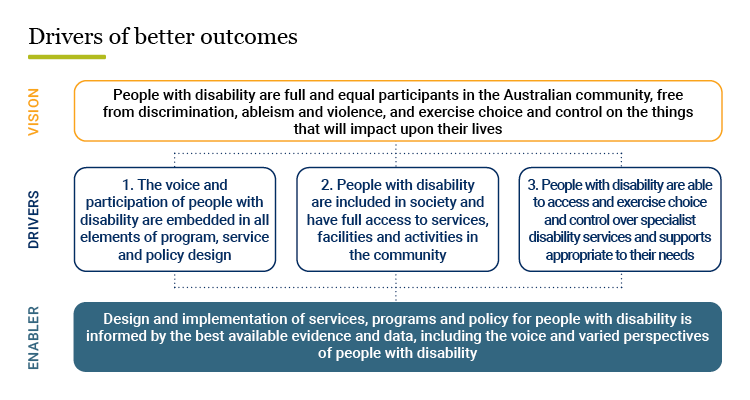

- SVA’s disability perspective paper outlines three core drivers that could help deliver better outcomes for people with disability.

- One of these drivers is embedding the voice and participation of people with disability in all elements of program, service and policy design.

- Disability advocates speak to the importance of having a voice, being heard, and of inclusion.

Disability advocate, Shanais Nielsen: “I hope that people with disabilities are included more in the decision-making that affects us.”

“In the future I hope to see more people with disabilities having the control and say over their lives. I hope that people with disabilities are included more in the decision-making that affects us as we are the ones living with the disability and we need to have the opportunities to make decisions and be listened to when decisions are being made. I hope to see more organisations seeking the input and contribution from people with disabilities to create a more inclusive environment.”

So said Shanais Nielsen, a disability advocate, speaking at the launch of SVA’s perspective paper on disability.

The importance of embedding the voice and participation of people with disability in all things that impact on their lives is at the heart of SVA Perspectives: Disability, and at the heart of improving outcomes for people with disability.

The paper looks closely at the experiences of people with disability in Australia, including both the specialist services under the National Disability Insurance Scheme and universal services such as health, transport, education and employment that people with disability access in their everyday life.

The paper also identifies the drivers or different elements that are required in order for people with disability to experience better life outcomes.

Better outcomes for people with disability is not just up to the disability sector, but the responsibility of the whole of society.

People with disability deserve to have the same rights and opportunities as everybody else. And most people with disability want to access the same things that people without disability do: a suitable job, a good education, housing that suits their needs and transport around their community.

At SVA, our vision is that people with disability are full and equal participants in our community, free from discrimination, ableism and violence. They should be able to exercise choice and control, and make decisions about the things that impact upon their lives.

Better outcomes for people with disability is not just up to the disability sector, but the responsibility of the whole of society.

In this article we summarise the current situation for people with disability, explore the three core drivers that we have identified could help deliver better outcomes, and explore in more depth why incorporating the voice of people with disability will enhance their experience of inclusion and wellbeing.

The current situation

Almost 20% of Australians (~4.3 million people) experience disability.1

The way in which society views people with disability can lead to isolation, discrimination and stigma as well as health issues. For many people with disability, there are connected experiences of poverty, social exclusion, violence and abuse, unemployment and homelessness as well as limited opportunities to have a say in what happens to them. For example, 55% of Australians who have a long-term health condition or disability experience some level of exclusion. Almost 16% experience deep social exclusion.2

… because of the failure of society to make our communities, public spaces, buildings, services and information inclusive and easier to access.

People with disability tend to be excluded and have poorer outcomes across areas such as education, employment, housing, and health and wellbeing when compared to other members of society. Some groups face several forms of social exclusion and discrimination at the same time, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, people who live in rural and remote areas and newly arrived refugees.

Many of the poor outcomes experienced by people with disability are not because of the person’s impairment, but because of the failure of society to make our communities, public spaces, buildings, services and information inclusive and easier to access. In the past, people with disability have had their basic human rights ignored and have experienced high levels of discrimination. Being left out and lacking choice and control over their lives has also resulted in a less tolerant and inclusive society where people with disability have been hidden, forgotten and purposely shut out of life.

The development of the National Disability Strategy in 2010 and the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in 2013 were landmark events for Australia.

The idea of the NDIS is to replace a system that was unfair, underfunded, fragmented and inefficient with an insurance scheme that will provide cover for all Australians in the event of significant disability and fund long-term high-quality care and support (but not income replacement).3 Whilst this has been a welcome change, there have been many teething issues and problems.

With so many changes to disability services and uncertainty about the future, what will help improve life outcomes for people with disability?

What are the drivers of improved outcomes?

By taking a systems approach to disability, including both specialist and universal services, we’ve identified what we see as the specific challenges faced by people with disability and the broader systems that people with disability access.

From this lens, we developed what we call a “driver tree” that pulls together all the different elements and parts of the system to highlight what is required to drive better outcomes for people with disability in Australia. The driver tree is designed to be strengths based and visionary – it’s not about the problem or issue, it’s about what we believe is required to drive better outcomes for people with disability.

1. The voice and participation of people with disability are embedded in all elements of program, service and policy design

The first driver captures the importance of creating opportunities and removing barriers for people with disability to participate and contribute their voice in all things that will impact upon their lives. We’ll explore this driver in more detail below.

2. People with disability are included in society and have full access to services, facilities and activities in the community

The second driver discusses taking a more targeted approach to increase inclusionary practices across universal services. It highlights that recognising and celebrating the contributions of people with disability is essential, as this will ensure we reduce the experiences of discrimination and exclusion.

Accessibility is a key driver of participation for people with disability. We need all services, spaces and information to be accessible for all people with disability, including public transport, schools, housing, health services and the justice system. For people with disability to be heard and feel valued, we need to create greater social inclusion and pathways to economic participation including alternate models of employment and income support.

3. People with disability access and exercise choice and control over specialist disability services and supports appropriate to their needs

The third driver speaks to the current range of specialist services in operation in Australia. It discusses:

- Australia’s National Disability Strategy and the NDIS as they stand presently, noting that they both will and should shift in the coming years.

- The need for quality information so people with disability can be empowered to navigate the system.

- The nature of services – what services are delivered, where they’re delivered, how they’re delivered and by whom, which includes both quality and affordability.

- The need for integration and flexibility both within the disability sector and between related service systems, including health, transport, justice, employment, education and training.

We also recognise that an essential enabler for all these drivers is that the best available evidence and data is used to design and implement services, programs and policies for people with disability, and crucially that this evidence includes the voices and varied perspectives of people with disability.

Having a voice is key to improving inclusion and wellbeing

The experiences of people with disability in Australia in the past have involved discrimination, isolation, segregation and a loss of personal power and independence.

Only we, the individuals, know what we need. Only we, the individuals, know what our goals are and what we want to achieve.

Therefore, the voice and participation of people with disability in all things that will impact upon their lives needs to be at the heart of anything aimed at improving the experiences of people with disability in Australia.

Shanais Nielsen knows first-hand why it is important for people with disability to participate, have a voice and be listened to.

“How do I view disability? There were always things growing up that I couldn’t do – and even though most people living with a disability make the most of what they have, as you get older you realise the importance of being able to be in control of the things you can do and the decisions you can make,” said Nielsen.

“Yes, there is a lot I can’t do. However, I can make decisions for myself and my support network can assist me when needed. Only we, the individuals, know what we need. Only we, the individuals, know what our goals are and what we want to achieve.

“We should have the right to be in control and do what we can, not other people that don’t know us making the decisions. We are all individuals and therefore need and want different things and we should have the opportunity to make these decisions when we can.”

Clearly, embedding the voice and participation of people with disability in all elements of program, service and policy design across the disability system as well as universal services is essential.

For people with disability to participate and contribute their voice and experiences, it is important that Australian society creates opportunities and removes barriers, so that they can deem what is right for themselves and have control over the things that will impact upon their own lives.

No individual with a disability is the same as another, we all have different goals, wants and needs.

As Nielsen explained, “It was extremely hard for me to have someone else that I had never met almost say ‘no, you can’t have that, no, you don’t need that’. It was mind blowing that they had so much to say about my life even though they had never met me or lived a day in my life yet they were able to decide what I needed and what I didn’t need.”

“From this experience it really made me realise how important it is for people with disabilities to have their say. Our voice, our control over what we need, as we know what we really want and what we need to feel fulfilled.”

“No individual with a disability is the same as another, we all have different goals, wants and needs. We are all different and I feel like this is why it is so important for us to be able to make our decisions about our life.”

Inclusion in decision-making and exercising choice and control go hand-in-hand in enabling the transformation required to improve the experiences and wellbeing of people with disability in Australia.

Meaningful participation is also essential if the needs of people with disability are to be met.

It gets to a point where it really affects your mental health and the people around you.

As Nielsen said, “Not having the control to make decisions and having input into such factors that affect us can be extremely deteriorating for the mind and body. That’s one thing I don’t think a lot of people understand – when they haven’t experienced a situation like this.”

“Being knocked back, declined and not in control of your life and the decisions that you make, that affect you time and time again, can be extremely exhausting. It gets to a point where it really affects your mental health and the people around you.”

Her story highlights that Australia still has further work to do to ensure all people with disability are involved in all decisions that affect them.

Culture of inclusion

It is also important to consider the right to self-determination and empowerment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability if their lives are to improve. Self-determination must be driven by Aboriginal people. While state and federal governments have a role in setting a coordinated national policy, they must be prepared to give up some decision-making authority and management responsibility, allowing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to assume greater control of their futures, especially given the higher rates of disability in these communities.4

Damian Griffis is CEO of First People’s Disability Network, a national human rights organisation of and for Australia’s first peoples with disability, their families and communities. Griffis said “We talk about moving beyond a social model of disability now, into what we call a culture of inclusion.

“In traditional Aboriginal language, there was no comparable word for disability so we just generally accepted people as they are.

“The western approach to disability requires labelling. There’s an endless list of labels as they relate to need, and we think that is highly problematic.

“The system doesn’t understand intersectional issues very well at all. So from our perspective, our members face discrimination based on their Aboriginality and/or their disability.

“In Australia, we generally have a system, where you have to pick your discrimination, which is weird frankly. We also encounter situations where there are unique needs for Australians with disability who live in regional and remote Australia.

The answers actually lie within the person that has the disability themselves.

“I go back to the fundamental problem that we have a power imbalance and we need to genuinely put the voices of people with disability at the forefront. That is taking the advice and wisdom of disabled peoples organisations. But to do that requires sometimes organisations to set their egos aside to be frank, and to recognise that they may not have the answers. The answers actually lie within the person that has the disability themselves.”

What can we all do to embed the voice of people with disability?

Many organisations display a general lack of understanding of disability and how they can change their approach to promote the inclusion and participation of people with disability.5 Sometimes they do not consider the different types of disability and varied perspectives and needs of people with disability, but with the right support and engagement of people with disability, this can change for the better.

Lynn Nguyen is Customer Strategy Manager with Scope Australia, a disability service provider. “Any organisation that puts the voice of the customer at the heart of what it does is signalling to me that it has its priorities in order,” she said.

“At Scope, we have a servicing score that guides how we do services and how we work with each other. Inherent in that is the idea that we are facilitators, we’re enablers, we’re capacity builders and we can’t do that without the voice of our clients. We are co-designing, co-creating experiences every single day with our clients. For me it’s really simple, it’s a business imperative.”

“Scope adopts almost a start-up view of innovation which is do a little, learn a little, do a little bit more,” says Nguyen. “So that iterative process is really important to the way that we do things. As much as possible we do that with our customers. We very much imbed a co-design approach to everything that we do but it is a work in progress. We’re just constantly trying to be better.”

To increase participation of people with disability, organisations could consider using accessible venues, providing accessible briefings or Easy English materials, setting meetings at the right pace and tone, and providing training on expectations so that people are clear on how they can contribute meaningfully.6 Otherwise, people may feel their involvement is token and they may drop out.

It’s simple really, asking them what they need to be able to participate and then doing it.

As Griffis said, “It’s really important to learn and understand the different ways that people communicate; there are many different forms of communication. We have board members that have intellectual disabilities for example and the way we support them to be on the board is that they have a support person with them. They could have a staff member that uses a communication board for example.

“My obligation is to understand that form of communication – it’s not the other way around — so everyone’s voice can potentially be accommodated. It’s just a matter of asking that person. It’s simple really, asking them what they need to be able to participate and then doing it.”

Conclusion

Empowering voice and participation will ensure better designed programs and services and means not repeating the mistakes of the past that led to discrimination, marginalisation, violence, segregation and isolation. It is vital that people with disability are included in all decisions that affect them, at all levels of policy and in all areas of public life, not just as clients or participants but as citizens.

We need to move away from a system, which is about labelling people and creating barriers, to a culture of inclusion.

Griffis remarked, “At Lake Mungo in New South Wales, which is one of the most significant archaeological sites in Australia, there has been a fairly recent discovery of a single footprint that was dated 25,000 years ago. So the theory is that there was a one legged man participating in a hunt and he was using a stick to be able to participate. So 20,000 years ago we had roles for our people with disability. We need to move away from a system, which is about labelling people and creating barriers, to a culture of inclusion.”

This powerful story highlights the importance of people with disability having a role within their communities. By embedding the voice and participation of people with disability into your program, service or policy design you can aim to deliver better quality services and more effective policies. We all need to think more about inclusionary practices within workplaces as well as everyday life, because only then will people with disability start to have better experiences of care, better outcomes and can lead fulfilling lives.

Authors: Katie Maskiell

Contributor: Patrick Flynn

1 R Reeve et al., Australia’s Social Pulse (Sydney, 2016).

2 The Brotherhood of St Laurence, Social Exclusion Monitor: Health, 2018.

3 Productivity Commission, Disability Care and Support, Report No. 54 (Canberra, 2011).

4 Social Ventures Australia, SVA Perspectives: First Australians (Sydney, 2016).

5 Catherine Grant, Participating in Arts- and Cultural-Sector Governance in Australia: Experiences and Views of People with Disability, Arts and Health 6, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 75–89, .

6 Frawley and Bigby, Inclusion in Political and Public Life: The Experiences of People with Intellectual Disability on Government Disability Advisory Bodies in Australia.