Indigenous evaluation: how you do it is as important as what you find out

Indigenous evaluation case study: how we did it, why the process was important, the critical insights we gained along the way and resulting implications for not only the client, Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa and Martu people, but also for evaluators and Indigenous program and policy makers.

- Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) was created by Martu 15 years ago to preserve Martu culture, build a viable, sustainable economy in Martu communities, and build pathways for young Martu to a healthy and prosperous future.

- In 2020, KJ engaged SVA to evaluate their impact on Martu between 2010 and 2020. It was essential that the evaluation reflected the Martu voice and captured Martu’s genuine experiences and feelings about KJ.

- To achieve this, the evaluation was carefully designed at the outset to be Martu-led. This meant that the methodology was pegged against outcomes that Martu said were important to them, was adaptive to Martu communities and was implemented alongside Martu community members.

- While the findings of the evaluation are important, so too is the process and methodology used. These demonstrate important lessons for the Martu community, evaluators and for Indigenous programs and policy makers.

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) is a Martu organisation – Martu are the traditional custodians of a vast area in the Western Desert of the Pilbara. In 2020, KJ engaged Social Ventures Australia Consulting (SVA) to evaluate their impact on Martu communities between 2010 and 2020. In that evaluation, Martu articulated 11 outcomes that were important to them and KJ’s contributions were measured against those outcomes.

This article does not share the results of that evaluation but rather reflects on and emphasises the importance of the process undertaken in an evaluation for and with Aboriginal communities. The full evaluation report can be found here.

“The evaluation demonstrated a genuinely indigenous-led approach that truly put the Martu voice at the centre.”

SVA has had a long working relationship with KJ and Martu communities with our first project dating back to 2010. We have been on a journey with KJ and Martu for 10 years and this evaluation was an opportunity to look back, listen and translate Martu’s experiences not only for KJ but also for those working in the Indigenous sector.

As Peter Johnson, co-founder of KJ said, “SVA’s 10 year evaluation of our impact on Martu communities has been a seminal piece of work not only for us as a Martu organisation, but also for Indigenous policy, evaluation and program design at a sector level.

“The evaluation demonstrated a genuinely Indigenous-led approach that truly put the Martu voice at the centre. A great example of an evaluation done in line with the Productivity Commission’s recent Indigenous Evaluation Strategy 2020.”1

Martu and KJ

In the 10 years working with Martu we have come to learn about where they come from and the journey they’ve had, all which helps us in our work with these communities.

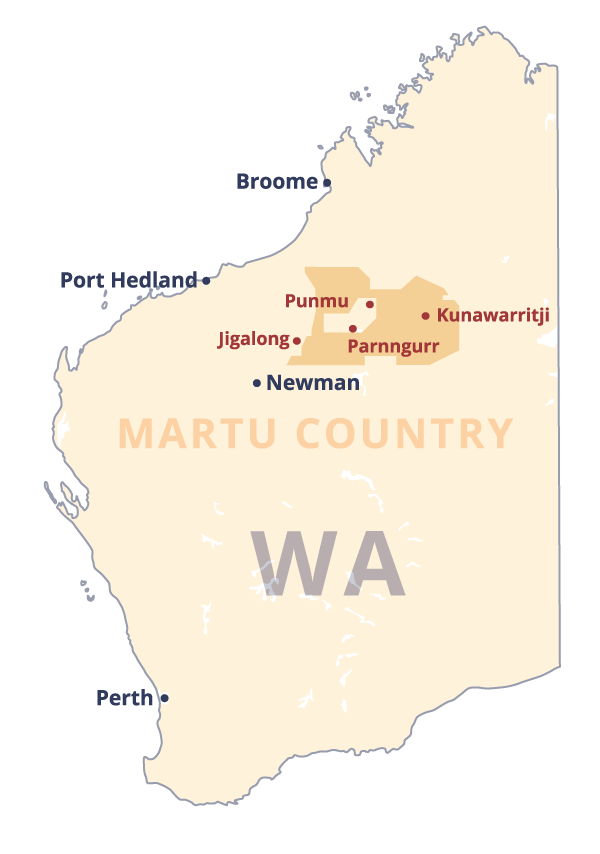

Martu country, part of the Great Sandy, Little Sandy and Gibson Deserts stretches from the Percival Lakes in the north to south of Lake Disappointment and far to the east of the Canning Stock Route, stretching towards the Western Australia and Northern Territory border. This vast area of desert has been described as ‘the harshest physical environment on earth ever inhabited by man before the Industrial Revolution’.2

Martu include people from several traditional language groups spread over their vast desert lands: Manyjilyjarra, Kartujarra, Putijarra, Warnman, Nyangajarra and Pijakarli.

Martu are among the last of Australia’s Indigenous people to make contact with the European world with many coming into stations and missions from a completely traditional desert way of life as recently as the 1960s. This happened in two main waves: Martu living around Lake Disappointment came out of the desert to Jigalong first in the 1930s and 1940s, but Martu living deep in the Western deserts did not move into stations and missions until the 1950s and 1960s.

In the early 1980s a group of four old men led Martu who had come in from the deep desert back from modern settlements in the Pilbara to remote desert locations. They began a process to build communities and gain native title over their country from the Australian Government. When these old leaders died in the mid-1990s it left a significant leadership vacuum in the communities.

‘The return of people to live on the country has supported the maintenance of law and custom among them.’

The Martu identify as one people. Their identity and their rights to their country were acknowledged in 2002, when their native title over much of their country was formally recognised. As the Native Title Tribunal noted:

‘There was no serious cultural break with their traditional roots. The return of people to live on the country has supported the maintenance of law and custom among them. They remain one of the most strongly ‘tradition-oriented’ groups of Aboriginal people in Australia today partly because of the protection that their physical environment gave them against non-Aboriginal intruders. It is not a welcoming environment for those who do not know how to locate and use its resources for survival. Of great importance is the continuing strength of their belief in the Dreaming.’3

The Martu are now concentrated in Port Hedland, Newman, Perth and several WA desert communities: Jigalong, Parnngurr, Punmu and Kunawarritji. (See map.) They remain a strong and distinctive Indigenous community, with a proud identity and history. Their story through the 20th century provides a fascinating insight into the experience of contact between Indigenous and white Australians.

KJ was created by Martu 15 years ago by elder, Muuki Taylor. It was created to preserve Martu culture; to build a viable, sustainable economy in Martu communities; and to build realistic pathways for young Martu to a healthy and prosperous future. To achieve this vision, KJ runs a suite of cultural, environmental and social programs in Martu communities and in Newman.

These programs seek to provide employment while preserving the deep Martu relationship with their country, maintaining the natural and cultural values of that country, creating greater Martu capacity to engage with Western agencies and developing Martu-led approaches to entrenched social problems.

KJ’s decision-making authority and power lies with Martu. KJ’s governing body is referred to as the KJ Board and consists of 12 Martu directors and three non-voting advisory directors.4 The 12 Martu directors include two each from five Martu communities and two from the Martu diaspora.

Due to the dominant focus on preservation of the natural and cultural values of Martu country, KJ’s programs are directed predominantly (although not exclusively) to Martu living in or near the Martu native title determination.

Designing a Martu-led evaluation

The evaluation had to reflect Martu’s experiences and feelings about KJ’s impact on their communities over the past 10 years.

It was therefore important that the methodology was pegged by outcomes that Martu value, was adaptive to Martu communities and captured the Martu voice. Further, it was critical that the evaluation did not impose conventional evaluative methods to quantify impact at the expense of authentic Martu assessments of KJ. This approach of centring the methodology around Martu (as opposed to imposing conventional methods) is in line with the Productivity Commission Indigenous Evaluation Strategy.

To ensure this intention carried through the project, a number of guiding principles were set and embedded into the evaluation’s design.

The following principles guided the evaluation:

- Who: This is a Martu story, by Martu, for Martu and ‘whitefellas’5 – This project was a chance for Martu to describe what outcomes are important to them and for all programs impacting Martu to be measured against those outcomes. The project was a chance for Martu to consider what has been successful (or not) from KJ’s work over the past 10 years, using a Martu frame of reference.

- How: Martu voices are central to the evaluation – The evaluation needed to tell the story of Martu experiences as a result of KJ’s contribution. Martu informed the design of the evaluation criteria and method for consultation. The consultation approach in Martu communities also needed to be led by Martu wherever possible and appropriate.

- What: The output of the evaluation will be shared with different audiences and complement other Martu and KJ research and stories – For Martu communities, this evaluation needed to support the evolution of how KJ and other organisations work with Martu. For funding bodies, this evaluation demonstrates the impact KJ has made on Martu communities through their support and investment over the past 10 years.

To ensure these principles were embedded from the outset, there were two key design elements that ensured Martu voices were central to the evaluation.

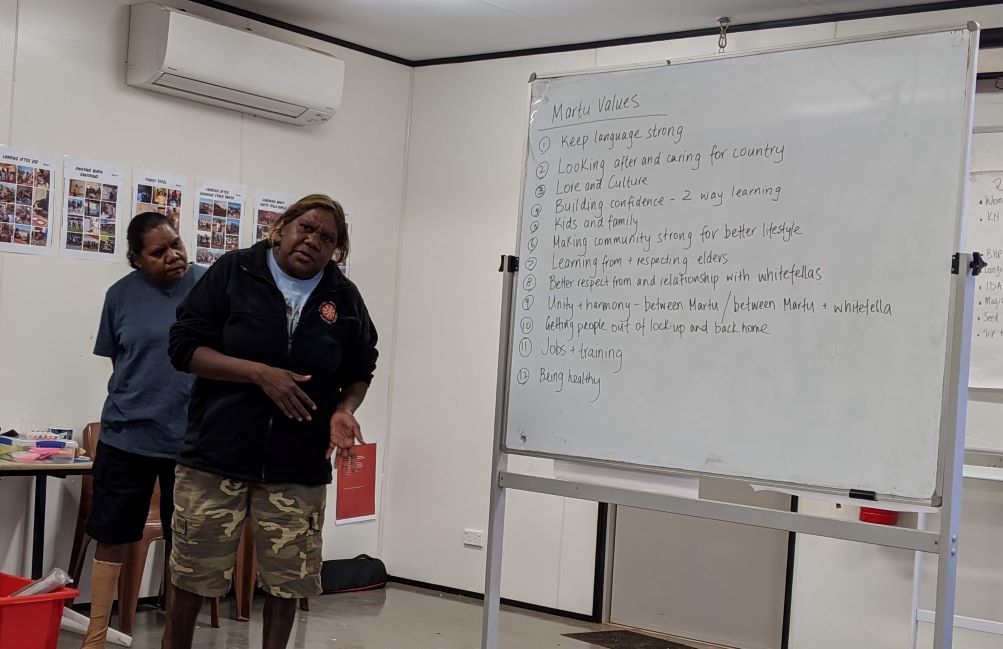

Firstly, two discovery workshops were held at the beginning of the evaluation with Martu Leadership Program (MLP) members6 to develop a list of Martu outcomes. These outcomes formed the foundation of the project and were used as indicators to assess KJ’s contribution. The outcomes were also reviewed at each Martu community consultation to ensure there was confirmation by the broader community.

‘Language is in the country and the country is alive. Martu need to know language, to know the country.’

The 11 outcomes are split by traditional (outcomes relating to the traditional Martu identity) and modern outcomes (outcomes relating to how Martu live in the modern world). The first five are traditional outcomes with the remaining six being modern outcomes. The outcomes are:

- Ngurra – Looking after and caring for country

‘You go home and you tell country you are coming and country knows you are coming.’ - Wangka – Keeping language strong

‘Language is in the country and the country is alive. Martu need to know language, to know the country.’ - Ninti – Learning from and respecting old people

‘Old people are the boss and the teachers. Listen to them. Make them feel happy and proud.’ - Walyja – Looking after kids and family

‘If you don’t know your family you are nobody. Look after family and funerals.’ - Kujungkarrini – Unity and harmony between Martu

‘We worked out where we fit together. We became kin with each other and not just individual families and fragmented.’ - Strong communities – Making community strong with high standard of living

‘In community we need better houses…We need better housing, so people come back to community…we are going around in circles and need action.’ - Confidence – Building confidence through two-way learning

‘We learn about white man world and black man world together.’ - Back to community – Getting people out of town, out of ‘lock-up’ (prison) and back to community

‘I went back and my spirit is good. Went to see my country. My spirit became itself again. I became reconnected to country. I went east and saw my country.’ - Respect – Better respect and relationship with ‘whitefellas’

‘Whitefella and Martu understanding each other and working together properly in a way that respects Martu.’ - Work – Work and training

‘More courses and more training and more skills and different jobs.’ - Health – Being healthy

‘There are a lot of problems. Blood pressure, diabetes, wama [alcohol], blocked arteries, ice, drugs coming in.’

Secondly, three to five MLP members were involved as co-facilitators in subsequent community consultation sessions. MLP members led workshops and acted as translators.

SVA’s long working relationship with KJ and Martu meant there was already a familiarity and trust between the evaluation team and the community.

These guiding principles and design elements helped ensure that the evaluation reflected the Martu voice. It is important to emphasise that KJ and Martu’s capacity and capability were key enabling factors to designing such a considered evaluation methodology. Without KJ’s intimate working relationship with Martu and the MLP members’ leadership skills, the design elements would not have been possible.

Since 2010 and SVA’s first project with KJ, many SVA staff members have had the privilege of being welcomed onto Martu Country and into community to sit with, listen to and learn from Martu. SVA’s long working relationship with KJ and Martu meant there was already a familiarity and trust between the evaluation team and the community which helped to enable an effective Martu-led design process.

Adapting the approach to meet community

While the methodology was designed with Martu at the outset of the evaluation, the importance of adapting to each community was built into the approach from the outset.

It was important to balance conventional evaluation rigour with what would work in community to ensure the authenticity of Martu engagement and assessment was not compromised.

To ensure this balance was maintained, the evaluation team adapted the methodology to ensure the Martu voice was captured and community dynamics were respected. For example:

- Initially, based on the discovery workshops with the MLP members, the evaluation team intended to assess individual KJ activities against the 11 outcomes via a voting exercise as a rigorous way of understanding what activities were making a difference and in what way. It was quickly discovered that that approach was not well received by community as it was too rigid. Martu were far more amenable to talking more freely in conversation, often during community activities such as shopping at the corner store or attending a barbeque.

- The consultation approach was adapted in each workshop to align with community dynamics and the use of Martu languages and English. For example, younger female community members were less likely to speak in a bigger group but were more open to giving feedback during one-on-one interviews. Older Martu community members were less likely to speak English therefore one-on-one interviews with local translators were more appropriate to ensure the richness of what they wanted to say was captured.

- Martu co-facilitators increasingly led community consultations as they became more familiar and confident with the evaluation process. It was observed that when co-facilitators led discussions, community members better understood the process and their role, were more engaged and spoke more openly about their experiences. The co-facilitators also became increasingly invested in the process and volunteered to help facilitate conversations more frequently to ensure the evaluators heard what community members had to say.

The importance of the evaluators’ mindset should also be acknowledged. The flexibility of an evaluator and their ability to readily adapt approaches to respect community dynamics and circumstances while balancing the need for rigour is important. In these cases, evaluators need to work with empathy while maintaining a keen eye on process.

Ending the evaluation

Seventy-five Martu were consulted with during the evaluation. At the end of the project, the evaluations findings were presented back to KJ’s board of directors. At that meeting, Martu board members confirmed the finding but also further reflected on the 11 outcomes that they described in the evaluation.

Interestingly, while the formal evaluation process had concluded, the Martu board members insisted on adding an additional twelfth outcome, safety to their list of outcomes. Relevantly, the importance of safety was added during a time when tensions and violence were escalating in Newman for Martu.

The inclusion of a twelfth outcome indicates ongoing engagement and ownership that Martu feel over the evaluation and the list of outcomes they articulated as important to them. For Martu, the evaluation process did not end after the report was submitted but continued to evolve and reflect changing circumstances in town and what matters most to them at the time.

Why this evaluation process was important

The methodology for this evaluation was carefully designed with Martu and adapted to ensure the centrality of the Martu voice. Martu’s ongoing ownership of the evaluation even after its formal conclusion indicates the importance of that methodology and process.

While the findings of an evaluation are important, so too is the process and methodology that evaluators undertake to arrive at those findings. The process for this evaluation was important:

- For the effectiveness of the evaluation itself – designing the evaluation with Martu and involving Martu at every stage led to more authentic and genuine Martu reflections about KJ. This is both because of the trust that Martu had in the process but also because the design included a list of outcomes that meant something to Martu and reflected matters that were most important to them.

- For the Martu community – As Martu were involved from the very outset and informed the process, there was a sense of ownership in the evaluation, particularly as it documented the list of outcomes that mattered to Martu. Martu can also hold other stakeholders such as funders or service providers accountable to those outcomes in the future. The process provided a capacity building opportunity in evaluation for MLP members.

- For evaluators – The evaluation process in this project presented important learnings for evaluation practitioners. It emphasised the importance of engaging meaningfully with community at every stage. The evaluation process was also a reminder that adapting methodologies to meet community is always an important part of any evaluation work and that evaluators should be ready to do so to respect the community voice.

- For Indigenous programs and policy makers – The set of outcomes articulated by Martu allowed the evaluation to capture a Martu world view, one where outcomes were not individual and distinct but rather interconnected, inextricably linked and dependent on one another. This revealed a key strength in the way KJ works: its programs are designed to respond to the holistic way that Martu think and are not dissected to align with specific outcomes. For example, both KJ’s on-country programs and the MLP are framed by a Martu worldview. They acknowledge the interconnected nature of issues and outcomes and the need for efforts to build on each other for long term change and engagement. Both programs focus on re-establishing traditional structures while also creating economic opportunities and engagement with mainstream Australia. Both programs were two of the most frequently cited contributors to positive outcomes by Martu.

Authors: Alison Kwok & Simon Faivel

Read the report1 Productivity Commission Indigenous Evaluation Strategy, 2020

2 Gould, Richard in Trautmann, Thomas and Peter Whiteley, Crow-Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Analysis, 2012.

3 Federal Court of Australia, James on behalf of the Martu People v State of Western Australia, [2002] FCA 1208.

4 Advisory directors provide expertise in financial management, regulatory compliance, law and prudent management advice but cannot vote, ensuring Martu have genuine control of major decisions.

5 Martu characterise Western society and mainstream systems, government and organisations as ‘whitefellas’. This article adopts that term for consistency with the Martu world view.

6 The Martu Leadership Program is an adult education program designed to inspire confidence and aspiration for social change among Martu. The program teaches Martu about mainstream law, structures and processes that have a high impact on Martu families and communities. These formal education activities are complemented by information education such as visits to cities, government agencies, businesses and other Indigenous communities.