Is your program suitable for the Outcomes Fund?

A practical guide to help you self-assess your program’s appropriateness for the Australian Government’s $100 million Outcomes Fund.

- The Outcomes Fund will provide more opportunities for outcomes contracts and social impact bonds (SIBs) in Australia.

- An outcomes contract or SIB is not suitable for all programs, and there are complex issues to work through in getting any outcomes contract or SIB proposal to stack up.

- SVA has developed practical ‘rules of thumb’ to do a feasibility check so you don’t waste your time exploring this funding approach.

An outcomes fund is a pool of money which is made available for projects with clear rules on the type of outcomes that are being paid for and amounts payable per outcome. It provides more opportunities for outcomes contracts and social impact bonds (SIBs). The advantages of using an outcomes fund is that it:

- Provides greater scale to test intervention models and generate insights about ‘what works’.

- Results in simple outcomes contracts and SIBs, and faster development times (and therefore lower cost).

- Provides clarity of key requirements for governments and service providers, fostering development of more, and more readily contractible, proposals.

The Australian Government is establishing its own $100 million outcomes fund1 (‘the Outcomes Fund’), which will provide payments to state and territory governments and service delivery organisations based on the measurable outcomes they achieve. While Australia is exploring its first outcomes fund, the United Kingdom has established several funds2 including the Life Chances Fund3.

Limited details about the Outcomes Fund are available at this stage, although the Australian Government has indicated that it will focus on three broad cohorts: people experiencing or at risk of homelessness, people experiencing high barriers to employment and children and families experiencing vulnerability. Service providers may be able to access funding via state and territory governments or directly through the Australian Government from 2025.

The allure of long-term funding for an early intervention or preventative program from the Outcomes Fund is understandable, however there are many stars that need to align for an outcomes contract or SIB to be viable. While SVA believes these types of funding arrangements have the potential to provide significant benefits to governments, service providers and investors alike, the reality is that they are not suitable funding instruments for all social programs.

This article provides key questions that organisations thinking of embarking on this journey should consider, and viability ‘rules of thumb’ for those questions. This article is based on the article ‘Is your program suitable for a social impact bond?’ authored by Elyse Sainty in 2015. Although this article was written almost a decade ago, many of the ‘rules of thumb’ are still applicable for any outcomes contract or SIB.

It should be noted that these ‘rules of thumb’ are just that. Failure to meet a benchmark does not mean that an outcomes contract or SIB is definitely not viable, but it does indicate where the challenges would lie in developing a successful contract. The Outcomes Fund will also have its own criteria for evaluating proposals that are not considered in this article, as will state and territory governments.

The big picture

Assessing a prospective outcomes contract involves testing that it is viable across three core aspects:

- Our proposal will satisfy government considerations. Usually that requires: the program generating meaningful impact or savings to government, and a statistically sound, practical measure of that impact or savings relative to a counterfactual4 is available.

- We will be able to deliver the outcomes required. A program exists, or could exist, that is highly likely to deliver the outcomes at a cost commensurate with the benefits.

- We can bear the financial risk if the program does not achieve the targeted outcomes. There is a risk that we may not get paid if the target outcomes are not achieved.

If the answer to the last question is ‘no’, then you will need to share the financial risk with someone else – typically with investors through a SIB. A prospective SIB has one additional aspect to consider: - We will be able to attract investors. The program can be funded during the period of time before outcome payments start to flow, by attracting investors to a SIB.

Each of these viability tests, and the key considerations that arise for each of them, are explored further below.

1. Would our proposal satisfy government considerations?

In some instances, governments may indicate the particular social problem they want to tackle through an outcomes-based contract, their preferred payment metrics5 and the value they attach to a positive outcome. However, clear government guidance on these key issues is not always available (although the hope is that the Outcomes Fund provides clear guidance on the target cohort, payment metrics, counterfactual estimates and payment structures). In the absence of this guidance, a number of critical factors need to be assessed:

- The ‘care factor’

- Population identification

- Measurement

- Fair attribution

The ‘care factor’

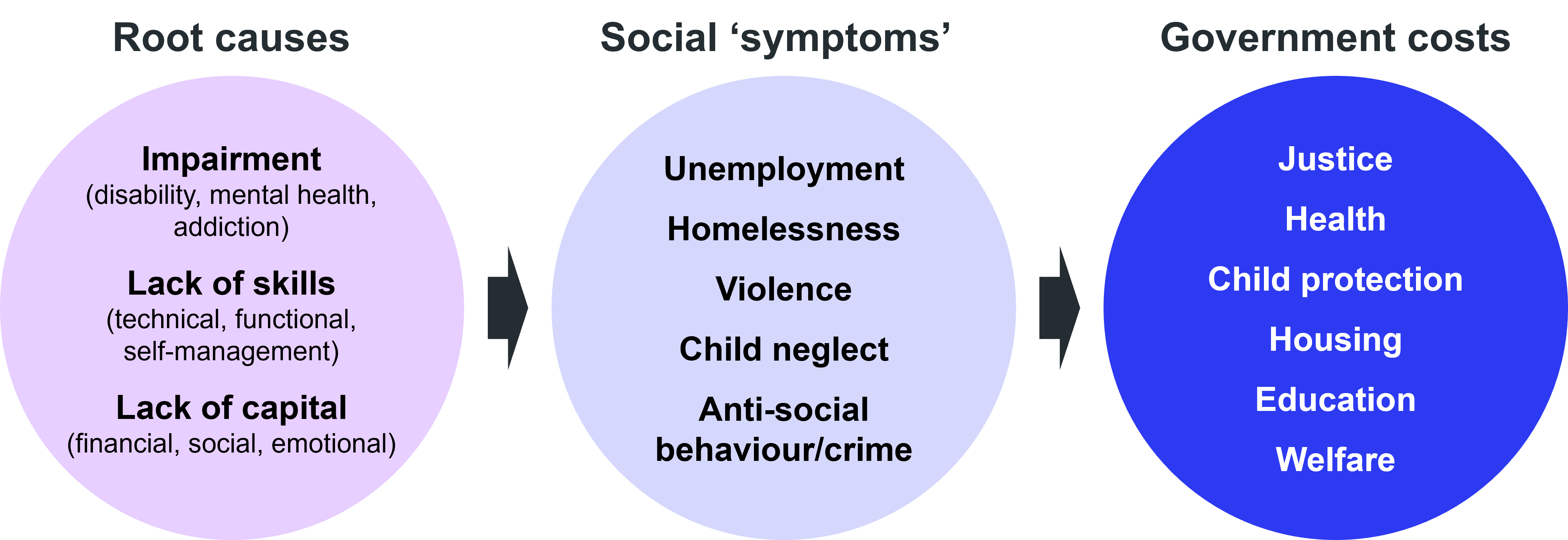

Many intervention programs are framed around the social ‘symptom’ they seek to alleviate; in developing an outcomes contract or SIB it is important to understand how these translate into government costs, and hence potential savings. In short, high cost problems get attention – the ‘care factor’ is high. The Outcomes Fund has identified its broad areas of interest (homelessness, employment and early years).

A complicating factor is that many social problems impact multiple layers of government, and multiple departments within a government. It is important to understand where the primary cost burden lies.

The Outcomes Fund will enable collaboration across the layers of government as in some cases it will involve both the Australian Government (through the Department of Social Services) and the state and territory governments.

Ideally a lead department can be identified in the relevant state or territory government that would have significant financial upside from a successful intervention. Without a clear driver within the state or territory government, the development phase could be protracted – or unsuccessful. This won’t be relevant for funding rounds only involving the Australian Government.

One of the key issues for government is how ‘cashable’ savings are. Fixed costs (for example running a prison or a hospital) may be difficult to reduce unless there is a substantial change in utilisation, whereas outlays directly related to an individual (for example, payments to foster carers or welfare payments) offer an immediate cash saving to government. Governments can use fully allocated costs as the basis for calculating savings, but in a constrained budgetary environment they are likely to focus on readily cashable savings.

Governments will also be cognisant of when potential savings will arise. There is a tension between the perceived efficiency of preventative programs and the long wait for associated benefits to accrue. Far-future savings are less certain to arise and are likely to create a timing mismatch between outcome payments and reduced costs. This will be an issue for many early years programs as governments are likely to place less emphasis on potential long-term savings (eg reduced offending, reduced welfare payments, reduced emergency accommodation usage) arising from programs working with younger children. Governments are thus less likely to take those potential savings into account when determining what they are prepared to pay for a successful outcome.

Population identification

The impacted population that generates government costs and could be targeted with a program needs to be large and objectively determined. Without a clear definition of the targeted population it is difficult to determine a baseline or a counterfactual against which the program’s success can be measured. For example, finding and assessing people ‘at risk of losing a job’ is much more problematic than people ‘employed less than 10 hours per week’.

The impacted population also needs to be sufficiently large that it can support a statistically significant measurement group6 (and potentially a matched control group).

Measurement

For outcomes contracts and SIBs, measurement is everything.

Measuring outcomes serves as a proxy for the determination of the social impact of a program. It is important that a suitable outcome metric(s) can be identified that is a fair and practical basis for outcome payments and is acceptable to all stakeholders. Choosing the right outcome metrics is critical, and considerations will include:

- the strength of correlation to financial and social impact;

- the benefits of simplicity in contracting, calculating and communicating outcomes;

- the ability to source robust data for both program participants and a counterfactual;

- the need to wait (possibly for several years) for outcomes to emerge; and

- the potential for perverse incentives.

Generally, data for the determination of outcomes (and hence calculation of payments) will be sourced from government databases. For example, the payment metric may be the number of convictions recorded, the number of periods receiving income support, the number of hours in work or work-like activities, or the number of hospital bed days.

It should be noted that the payment metrics sit within a broader measurement and evaluation framework that underpins the service provider’s performance management.

Fair attribution

To determine the extent to which a positive outcome can be attributed to a program, results are compared with a ‘counterfactual’. The counterfactual is the estimation of what would have happened in the absence of the program. The counterfactual may be determined in a number of ways, including by reference to:

- the experience of a statistically matched control group drawn from the untreated population;

- historical outcomes for the target population; or

- the outcomes for a correlated population (eg in another state, or another age group).

There is likely to be a trade-off between accuracy and complexity in determining a fair counterfactual.

| Key government considerations | Viability ‘rule of thumb’ |

|---|---|

| Does the social problem create significant government costs? | >$100m annual costs for a single state government department can be linked to the social problem the program targets (for the total impacted population). |

| Are baseline government costs per person incurred over a relatively short time period? | >80% of future costs attributable to an individual will arise within 5 years. |

| Are government costs fixed or variable in nature? | >50% of costs are variable, or the scale of the intervention program is very large. |

| Is the impacted population sufficiently large and clearly identifiable? | >3,000 people are currently in the impacted population. It is reasonably straightforward to define the impacted population and identify who is within it at any point in time. |

| Are there simple/ unambiguous measures that are a sound indicator of government savings? | Existing government data systems should be able to provide outcome data that is closely linked to the financial and social benefits of the program. |

| Can a counterfactual be fairly determined? | Historic outcome data is available for the impacted population. |

2. Will we be able to deliver the outcomes required?

The commissioning government will require a high level of confidence that the proposed program will be able to generate sufficient social and financial outcomes (and hence outcome payments). Potential investors will also require this for a SIB. Critical issues are:

- Program logic and evidence base

- Scale

- Organisational capacity

- Program cost

Program logic and evidence base

A tension exists between the potential for innovation in program design and the need for a credible evidence base to demonstrate that it will work. At this stage of the market’s development, evidence trumps innovation.

The ‘theory of change’ and detailed program design (activities and services, segmentation, scale, location, duration of support, referral/induction, staffing, systems and data management) all need to be clearly articulated in any outcomes contract or SIB proposal. While most of these elements are no different to non-outcomes funded programs, there is greater emphasis on some issues. For example, client referral and induction processes are critical in determining who exactly is on the program and when they entered it (for measurement purposes).

The estimate of the likely impact of the program is generally expressed as a percentage, for example, ‘government costs will be reduced by X%’. X is the ‘magic number’, and a strong rationale needs to be built for how it is determined, especially if X is large. While very few service providers can point to the published results of randomised control trials, strong evidence such as academic research or externally verified data from a current or commensurate program is desirable. For SIBs and outcomes contracts, anecdotes are rarely an adequate level of evidence.

Scale

The program needs to be large enough that it generates statistically significant results and sufficient government savings to justify the time and cost of developing an outcomes contract or SIB.

Organisational capacity

Service providers need to be able to demonstrate that they have the capacity and capability to manage both the development and delivery of the program.

The development phase requires time, data and sound analysis to work through the many complex issues that arise. The service provider needs to be able to cover the direct and indirect costs of participating in this process, including senior personnel with finance and service delivery expertise, as well as outlays including legal costs.

Once the contracts are in place, the service provider will need to be able to effectively manage the roll out and ongoing performance of the program, with a strong focus on delivering outcomes. The involvement of investors will likely see a greater emphasis on governance and performance reporting relative to non-outcomes funded programs.

Program cost

The economic viability of an outcomes contract or SIB hinges on the relationship between program costs and government savings. It is useful to express overall program costs on a per person basis to be able to compare them with the estimate of average per person government savings.

In estimating program costs, consideration needs to be given to any investment required to build delivery capability, and to the long-term nature of outcome contracts.

| Key service provider considerations | Viability ‘rule of thumb’ |

|---|---|

| Is the program logic sound, and will it deliver results? | The proposal is based upon an existing program (here or elsewhere) with well documented processes/methodology and strong evaluation. A reasonable evidence base supports the estimate of the level of success – internally produced data for comparable outcome metrics or directly applicable academic research. |

| Can the program be implemented at sufficient scale? | >500 individuals in the intervention group (with intake spread over 3-5 years). >$20m gross government savings.7 |

| Can sufficient resources be devoted to developing the SIB? | > $150,000 funding is available to cover resourcing and outlays during the development phase (via internal reserves, donor support or government subsidy). |

| Will the program be effectively run? | A high level implementation plan has been scoped, including resourcing and operational management. The organisation has strong governance and financial controls and client management systems, and a track record of managing large scale programs or strong growth. |

| Can the program be delivered at a cost commensurate with the benefits? | Program delivery cost is less than half of estimated gross government savings per participant. |

3. Can we bear the financial risk of the outcomes contract?

The commercial reality of an outcomes contract is that you may not get paid if the target outcomes are not achieved. The financial loss your organisation stands to lose may be greater than the financial loss your organisation can realistically accept.

For example, an organisation currently has revenue of $5 million per year with net income of $100,000 per year and net assets of $2 million. The organisation is considering entering into an outcomes contract worth $10 million over six years. The organisation could lose $3 million if the target outcomes are not achieved (ie program costs are $3 million more than the total payments received if the target outcomes are not achieved). This commercial proposition is likely to make the organisation uncomfortable as the financial loss will impact the broader operations of the organisation.

There is no viability ‘rule of thumb’ as all organisations have different risk appetites, and the amount of financial risk of the outcomes contract will depend on the total cost of the program and the mixture of fixed and outcomes payments.

However, every organisation considering an outcomes contract or SIB should define their ‘maximum tolerable loss’ – that is, the maximum amount the organisation is prepared to lose financially (it could be nil). If the potential financial loss arising from an outcomes contract is greater than an organisation’s maximum tolerable loss, then they should look to share the financial risk with investors through a SIB, or with philanthropy.

4. Will we be able to attract investors?

If a SIB is required, then there are additional considerations to assess viability. As with any investment, SIB investors will consider a range of issues, including:

- Return (both social and financial)

- Risk

- Size of investment

- Liquidity and term

Detailed guidance on how organisations can attract and engage with investors is available here.

Return

To some extent, social return will be ‘in the eye of the beholder’, based on the investor’s perception of the social problem being addressed. A clear articulation of the nature and scale of the problem and an impact measurement framework (incorporating but broader than the payment metrics) are important.

The appropriate level of financial return will depend upon many factors, including the nature of prospective investors, the level of risk and the level of social return, and will sit somewhere on the spectrum between philanthropy and purely commercial terms.

Risk

Assessing the risks associated with a SIB investment poses some unusual challenges. Investors will potentially be exposed to risks such as a smaller than expected number of program participants, or a better than anticipated counterfactual outcome (making it harder to generate improvements) – in addition to the key risk of program efficacy – which may be difficult for them to analyse.

A key consideration for investors is the proportion of their capital that is at risk in a worst-case scenario (ie if the program does not generate outcomes any better than the counterfactual). Capital loss can be mitigated in a range of ways, including government risk sharing (achieved through structures such as minimum payments or part guarantees), a philanthropic or first loss tier, and early termination provisions for underperformance.

Investors will also consider whether the service provider is wearing any of the risk. The higher the degree of ‘skin in the game’ for the service provider, the greater the alignment of interests, providing investors with confidence that program design and management will be responsive to experience and emerging outcome data.

Size of investment

Broadly, the amount of capital that needs to be raised is equal to several years’ program costs plus the ‘overheads’ of establishing and running the SIB (in particular, legal, intermediary and evaluation costs), although this figure is highly dependent upon the structure of outcome payments and any other funding sources (for example fixed government payments).

The smaller the SIB, the higher the overhead establishment costs as a proportion of the capital proceeds. Small SIBs are also unlikely to appeal to institutional investors, who prefer larger scale investments to justify their due diligence costs. Overall, the bigger, the better from a cost effectiveness perspective.

Liquidity and term

SIBs are generally illiquid instruments, so investors will expect to ‘buy and hold’ until maturity. This makes the term of the bond an important consideration.

| Key investor considerations | Viability ‘rule of thumb’ |

|---|---|

| Will investors be motivated by the social problem the program targets? | Existing supporter base or widespread understanding of the impact of the problem. |

| Is the return appropriate? | >Cash rate + 5% target or best estimate return. |

| Is the maximum investor downside appropriate? | <50% capital loss in worst case scenario. |

| Does the service provider have the capacity for risk sharing? | A material component of outcome-based payment is financially viable, or the service provider could co-invest in the bond. |

| Is the potential bond size appropriate? | >$5m. |

| Is the potential bond term appropriate? | 4 – 10 years. |

Conclusion

Outcomes contracts and SIBs are an innovative and promising addition to the social services landscape, but they are not a silver bullet. Governments, service providers and investors need to work through a number of complex issues in determining whether an outcomes contract or SIB proposal stacks up.

For any organisation considering whether an outcomes contract or SIB would suit its program, it is worthwhile running the ruler over these key elements to assess the viability of the potential arrangement. With its extensive expertise in the development and delivery of outcomes contracts, SVA has developed ‘rules of thumb’ to help organisations conduct this high level assessment.

If you believe you have a potentially viable proposal, intermediaries like SVA can help you develop and ‘stress test’ the details, and prepare for the next steps in the development process.

For examples of SIBs developed by SVA, including information memorandums which outline SIB investment opportunities to potential investors, see our website.

Author: Patrick Bollen

Based on an article by Elyse Sainty

1 Commonwealth Outcomes Fund, Australian Government Treasury website, accessed 23 September 2024

2 Outcomes Funds, UK’s Government Outcomes Lab (GO Lab) website, accessed 23 September 2024

3 Life Chances Fund, UK’s Government Outcomes Lab (GO Lab) website, accessed 23 September 2024

4 The ‘counterfactual’ is the estimate of what would have happened in the absence of an intervention program.

5 A payment metric is a measurement that forms the basis of the calculation of outcomes payments made by the government.

6 The ‘measurement group’ is all the individuals that are referred to the program.

7 Gross savings = Number of individuals × Baseline government cost per person × X% reduction.