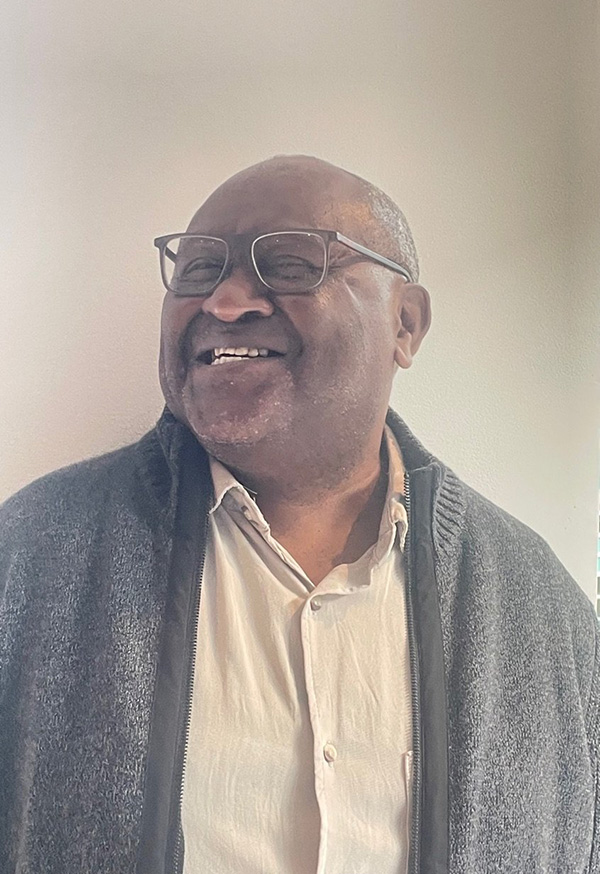

John Harding: on elders, the Voice and storytelling

For NAIDOC week, we sat down with John Harding, a highly skilled storyteller and communicator, about his role as First Nations Practice Lead at SVA.

- Born in Melbourne, John Harding is a Kuku Yalanji and a Meriam man from the Kuku Yalanji tribe of far north Queensland and eastern group of islands in the Torres Strait.

- Much of John’s life has been as a writer and storyteller in the arts.

- His focus at SVA to date has been progressing the idea of a First Nations Council which would provide some overall strategic thinking for SVA’s work with First Nations organisations and communities. John’s other focus is updating the cultural competency information available to staff.

- In regards to the Voice, John is clear that our role as a non-Indigenous organisation is to listen to what the Yes campaign needs and how they’re saying we can contribute.

- On this year’s NAIDOC theme: For our Elders, John says he always values the advice of elders and always has.

John Harding is a Kuku Yalanji and a Meriam man from the Kuku Yalanji tribe of far north Queensland and eastern group of islands in the Torres Strait. His mother comes from the village of Peidu on Darnley Island, or Erub.

Born and bred in Melbourne, John has lived there most of his life, although work with state and national organisations, means that he is deeply connected to many First Nations people and communities in Victoria and across Australia.

Storytelling and role as writer and director

Much of John’s life has been as a writer and storyteller in the arts.

John describes himself as a dreamer, and an entertainer from an early age. “At school I found I could make people laugh, and by the time I got to high school, I realised that my storytelling ability could make me friends and get me out of trouble.”

He also wrote poetry, something he hid under his bed given the suburb he grew up in. “They weren’t really arty people around my part of the woods.”

It wasn’t until his 20s that he read his poetry – on a radio station – and from there he started writing plays.

You can take stories and create a sense of unity in everyone.””

Since then John has had numerous roles in the arts, as writer and director for radio, film, and theatre, working extensively for Indigenous artistic expression particularly in theatre.

John founded The Ilbijerri Theatre in 1991, the oldest continuous First Nations theatre company in existence, for which he was made The National NAIDOC Artist of the year in 1992.

For someone from a working-class background, he says, the storytelling has often provided a kind of glue because you find the commonality between human beings through storytelling.

“That’s the great power of playwriting and theatre. Because when the audience is in the room, and it’s dark, they’re all laughing and crying at the same time, because you’ve found a common bond. You can take stories and create a sense of unity in everyone.”

He recognises too that it’s been the storytelling that has created possibilities in many of the jobs he’s had.

“Because, in any of our great leaders, our great political leaders, religious leaders, they’ve always been really good at telling a story and articulating a vision. And it’s the vision that brings everyone together. It’s the strength of that story that gets people behind you.”

Giving young people a voice

One of John’s key passions is the importance of young people having a voice and much of his work has been dedicated to making changes that benefit young people.

His first ‘job’ was working with youngsters ranging from five to 16-year-olds from Fitzroy’s social housing and it laid the foundation for his views on youth.

… it showed me that the youth have so much potential, and most of its untapped, because they’re very rarely represented.””

“We’d take these young kids to Albert Park Beach and the Melbourne Zoo, or for a game of football.

“And they bonded. All of a sudden the 10-year-old was holding a five-year-old kids hand; I didn’t have to hold the five-year-old’s hand anymore.

“They took that responsibility to make sure we had a good time. And that shows the power of youth, that it’s innate in all human beings to nurture and protect. And it showed me that the youth have so much potential, and most of its untapped, because they’re very rarely represented.”

“That’s always been my broad passion: to not just support youth, but enable them to have a platform and a voice so they can speak for themselves. Too often, they’re not spoken to, they’re spoken about.”

“It’s the same for First Nations kids, the way we always seem to be nothing but trouble. There’s no admiration of the beauty of our youth. Yet when we’re all young, we thought were the most important people on earth. So that’s been my passion. And I’ve always been attracted to jobs where I can achieve that in some small way.”

Later work involved facilitating a mentoring program at RMIT and as an associate lecturer in the School of Art.

Philanthropy and First Nations communities

Over his many years working in Indigenous affairs and through his work at Red Cross as national manager of an employment program for young people, John noticed a significant gap between philanthropists and First Nations communities.

“There was a lot of ignorance in philanthropy of First Nations communities. They all seemed to have this desire to help, but they weren’t making enough of an effort to reach out.”

He co-founded the Barmal Bijiril Foundation to facilitate meaningful connections and support First Nations peoples working in philanthropy.

It showed that there were two worlds existing, and what First Nations people often take for granted, organisations hadn’t even thought of.””

Barmal Bijiril initially brought together a network of Indigenous staff working in philanthropic organisations across the country to share their experiences and provide cultural support to each other. The group also brainstormed numerous initiatives that it could work on to address issues in philanthropy.

One of these initiatives focused on cultural safety within philanthropic organisations, offering webinars to CEOs on creating inclusive environments for Indigenous employees. As a result, the participants expressed newfound awareness of things to consider.

John remarks, “It showed that there were two worlds existing, and what First Nations people often take for granted, organisations hadn’t even thought of.”

“Another initiative aimed to connect philanthropic organisations with specific Indigenous communities around particular themes, say funding young women in STEM and facilitate them getting to know each other and collaborating around that funding.”

Barmal Bijiril was also keen to foster dialogue and collaboration between philanthropic organisations and Indigenous communities and organisations. They envisioned truth-telling forums where philanthropic trustees could learn about the history of the country, the source of their wealth and develop meaningful relationships based on that truth-telling.

Unfortunately, financial support for these projects was challenging to obtain. Though it’s still progressing with an ACNC application to achieve registered charitable status.

“Those kind of things are just a win-win for everybody. If you look at the economics of it, it’s quite cheap. It doesn’t cost much for these projects to actually happen.”

What drew him to SVA?

It was his work at Barmal Bijiriil as well as earlier work in employment strategies that drew John to SVA.

Over his career, John has worked in four organisations on their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment strategies. One in 1995 was with the then Australian Film Commission, now Screen Australia. The strategy aimed to get First Nations people behind the camera, in the technical, directorial and production roles. “The rationale being that if you can get young people behind the camera as camera assistants, it’s a really good way for them to get into the industry – get their names known and get a work record.“

He had what he described as a tiny budget to cover the whole country. The program effectively subsidised the First Nations employees, so that it cost the production companies and TV stations 50% less to employ them.

“As a result of that, 18 or 19 people worked on TV shows, movie sets and documentaries around the country for anything from 2-8 weeks in that 12 months. Some of them went on to become quite famous.”

SVA is in such a great position to be able to help First Nations people…””

“But I always thought wow if that could have been done on scale; if that budget was 10 times more, the impact could have been incredible.”

It was that eye for impact at scale that drew John to SVA.

“SVA looks at a model that works and asks what do we need to do to have national impact. When I saw SVA’s job ad, I thought about that job at Screen Australia and that SVA is in such a great position to be able to help First Nations people, because we’re never short on ideas. We’ve got 230 more years of ideas since colonization. We’re just short on money and support.”

His focus at SVA to date has been progressing the idea of a First Nations Council which would provide some overall strategic thinking for SVA’s work with First Nations organisations and communities. His initial focus is identifying and articulating exactly what the Council’s role will be and who should be on the Council.

John’s other focus is updating the cultural competency information currently available to all staff.

He’s also keen to progress the dissemination of the First Nations Practice Principles, both to finalise the material content, and produce a public version that is more accessible for other organisations to access and apply themselves.

“It’s going to be an evolving set of principles, but it’s quite coherent for what it is right now. A lot of work has been put into this. And it’s come from the life experiences of the consultants that have been involved, as well as the broader organisation of SVA. That should be recognised and acknowledged. So I think it is really important to share them.”

And of course, John will be assisting with SVA’s contribution to the Yes campaign.

What is his personal opinion of the Voice as a First Nations leader?

In his lifetime, John reckons he’s seen four or five different versions of the Voice – some government instruments and one or two, with a lot of community consultation from the ground up.

“The Voice is an important step forward. I was a regional councillor for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) which was dismantled in March 2005. So we actually haven’t had a national voice for nearly 20 years. We currently have NATSILS (the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service), NACCHO (the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation) and other peak bodies, then we have all these associated government departments, all this funding and all the policies they’re writing. I have no idea whether they have historically listened to our peak bodies or where they’re getting advice from. And that can be quite scary, because you’re dealing with people and children’s lives. And if these ideas are just coming from bureaucrats, who haven’t been elected, most of which aren’t First Nations, then that is not a good base from which to operate.

That it will take a referendum to get rid of the Voice from the Constitution, that’s a good thing.””

“We’ve seen some huge crises just in the last 20 to 30 years, in public policies of all kinds affecting us. And often, it’s because there’s a severe lack of consultation – even though we have national bodies like NACCHO and NATSILS.

“They’re often seen as lobbying government, they’re seen very much as external to government. So the government can discard their advice at a whim. I’m sure they’ve taken on board some advice, they’ve discarded some advice, just like they do with other lobbyists, but there’s no way that they [those organisations] can force their advice upon them [the government]. There’s no channel.

“While the Voice doesn’t have a budget for programs, or any guarantees from future governments, the fact is that it’s going to be in the Constitution, and it can’t be voted out by a party winning an election. That it will take a referendum to get rid of the Voice from the Constitution, that’s a good thing. I just hope that the advice that is given is taken seriously as it will be flowing from the grass roots representatives who know the solutions.

“Also the government is responsible for setting up the actual structure of the Voice. So there’s a couple of reasons why, you can see that there could be stumbling blocks in the first few years, the same as there would be for any new innovation.”

What approach should SVA as a non-Indigenous organisation be taking?

John is clear that our role as a non-Indigenous organisation is to listen to what the Yes campaign needs and how they’re saying we can contribute, rather than imposing our ideas on the campaign.

All you can do is say we’re available to assist you and leave it at that.””

“We should be saying, ‘we’re available with these resources, skills and time’, and let them choose how they want us to support them.

“It’s really up to them to decide but that’s true self determination. All you can do is say we’re available to assist you and leave it at that.

“I know it’s a hard thing, historically; non-Indigenous organisations that want to help sometimes find it difficult not to suggest or impose.

“This is a time in our history where true allies present themselves and say, ‘I’m available to assist, and use me however you want to use me’. That’s what true allies do. It’s what true friends do.”

As far as SVA’s support of the Voice, it’s been a privilege to be asked by the Yes campaign to contribute some of our campaigning expertise to their efforts.

SVA will continue to help mobilise the support of charities and corporate leaders that we work with for the campaign through providing a platform to campaign speakers at events and producing and disseminating related content. The organisation also continues to facilitate conversations with staff within the organisation most recently having Kenny Bedford, Indigenous engagement officer with the Yes campaign, speak to staff during National Reconciliation Week.

For our Elders: NAIDOC theme

When asked about this year’s NAIDOC theme: For our Elders, John responds with his signature chuckle: “I’m nearly an elder myself! I am still waiting for my invite to the Melbourne Elders luncheon.”

Switching quickly, he expresses the value he gives elders in two ways. In almost any initiative he’s been involved with, the first thing he’ll do is set up an advisory committee. “I find a couple of elders to sit on that advisory committee and then I’ll go find the people with the relevant skills or experience.

I always say when one passes, there goes another library.””

“I always value the wisdom of elders, because they have a much more strategic overview. They don’t get caught up in the everyday mechanics of things. Many of us live in a bubble. You find with a lot of elders that they’re not trapped in bubbles, their life experience has taught them to have a bird’s eye view of life. And that’s what you want, strategically, when you’re trying to set up an Aboriginal employment strategy for example.

“I always value the advice of elders and always have.”

The other way, he says, that elders are so important is that they are a vast repository of knowledge.

“I always say when one passes, there goes another library. Because they’re walking libraries of the history of our country. People that are born in the 1930s they’ve seen a world war, the Korean war, the Vietnam War. They’ve lived through all that. They’ve seen many, many prime ministers; they’ve lived under the White Australia Policy when they weren’t even considered citizens. And now they’re watching us get a Voice.

“I’m always stressing to young people: go and get your phone, all you need to do is press record. Go and capture your grandmother’s story because when she’s gone, her library’s gone.”