Making replication work

Seven observations from a review of initiatives that have replicated their model to increase social impact.

- Small, community-based organisations are well-placed to innovate in social service design and delivery as well as informing the broader social service landscape.

- Replication is one way that these organisations can increase their impact.

- The seven ventures reviewed all identified and maintained a convincing value proposition, maintained some measure of control over design and delivery, and measured and tracked just the essentials.

- The initiatives also all stayed true to their purpose and many demonstrated the potential for relatively small-scale ventures to influence the underlying conditions of the social sector in which they operate.

Small, community-based organisations are well-placed to innovate in social service design and delivery. Their work is embedded in community, they only exist because they are serving a real need, and they are relatively nimble in their ability to change and innovate.

In turn, this innovation has the potential to inform and influence more effective practice, funding, collaboration and policy across social service systems, and so support ever greater numbers of people to overcome the barriers they face.

For organisations that aspire to increase their breadth of impact (and not all do), replication is one way of doing this. However very few succeed to replicate beyond a handful of locations or communities. Nevertheless, during the past 15 years, a number of Australian organisations have achieved greater scale with incredible results, for example:

- AIME Mentoring (AIME) took just 10 years to create a program that reaches over 10% of all indigenous high school students in Australia, with impressive impact results. The program went global in 2017. AIME now aspires to reach 100,000 students globally by 2021.

- Men’s Shed went from an independent group of 25 sheds across South Eastern Australia in 2005 to a 1,000-shed member organisation in Australia, representing over 150,000 men and a strong voice for men’s health nationally, with a further 2,000 sheds in total in five other countries.

- The Song Room, which works with Australia’s most disadvantaged children through high-quality, tailored, arts-learning programs delivered in schools, launched its Teaching Artist Program in 2005. Within four years, that program had reached 20,000 students a year.

Enterprise-level and system barriers to replication persist. However, given the success of a small group of organisations in scaling their impact through replication, SVA has reviewed seven success cases to glean practical lessons. We share these lessons and observations to provoke reflection and sharing among ventures, funders and other social sector stakeholders.

Methodology and definitions

The seven social ventures reviewed all operate in Australia and have succeeded in replicating over the past 15 years. (See Table 1 below.)

The definition of venture is ‘the thing being replicated, whether this is an organisation, program or set of principles’ – taken from the Spring Impact Social Replication Toolkit.[1]

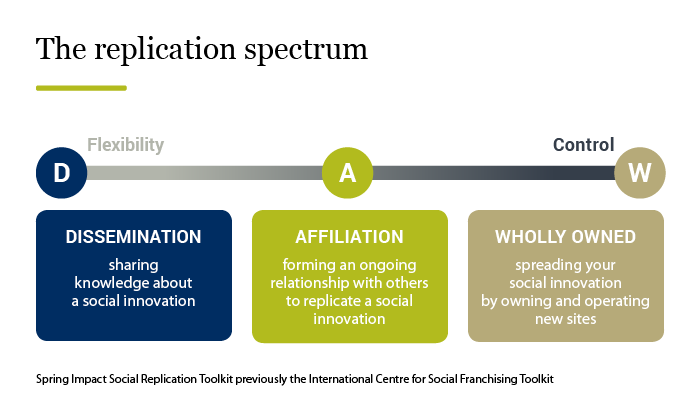

The Social Replication Toolkit presents a useful ‘replication spectrum’ (see Figure 1) which classifies the nature of the replication according to the level of control that the original venture maintains as the initiative is replicated.

An obvious, but important, caveat is that every organisation and social replication journey is and should be treated differently.

The Spring Impact Toolkit also defines the concepts of ‘originator’ (the individual or organisation looking to replicate their venture) and ‘implementer’ (the individual or organisation who are replicating the originator’s venture).

As well as interviewing originators of all seven ventures, we spoke to experts with experience in private sector franchise and licencing and social sector replication. We particularly focussed on better understanding:

- The nature and intention of the originator’s aspiration to scale by replication

- The path(s) taken to achieve success and how much the path(s) changed along the way

- The relationships between the original organisation and the partners involved in the replication, especially the two-way flows of cash, products and services.

Australian context

The Australian social services sector is mature and sophisticated relative to many other international contexts. It is unlikely that a single organisation could, or should, displace or revolutionise a given social service system.

For example, Men’s Shed has succeeded in reaching over 150,000 men since it identified the challenge of isolation facing many older men, particularly outside the capital cities. However, despite Men’s Shed’s success in replicating, the organisation complements, or is an alternative to, existing services that can be hard to access.

Related to this is the key role of government as a funder in Australia. Any successful innovation will almost inevitably be funded by, or mainstreamed within, a government service; the ‘Government adoption’ end-game (see Stanford Social Innovation Review article, What’s your endgame?).

Australian philanthropy plays an important, but relatively marginal role, accounting for an estimated $7 billion of approximately $500 billion spent annually on social services each year.[2] Long term philanthropic support is possible but not as prevalent as in other markets like the USA. The result again, from the outset, is that the venture must demonstrate how it can fit within the government-funded service system and influence government if it is to replicate or scale.

Ventures face significant time pressure to replicate (and scale) or lose philanthropic support as philanthropic funders often see their role as a short-term funder of innovation before government takes over.

The seven ventures

See the table below for statistics on the seven initiatives that we reviewed.

| Venture | Domain | Part of larger org? | Year established* | No of reps** | No of people supported | Geographic scope*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIME | First Australians/ Disadvantaged youth | N/A | 2005 | 450+ schools | 10,000+ a year | All states & territories |

| Beacon Foundation | Youth employment | N/A | 1988 | 145 schools | 15,000 a year | All states & territories |

| DRUMBEAT | Social and emotional learning | Holyoake | 2003 | 1000+ schools | 100,000+ impacted total | All states & territories & overseas |

| Foyer Foundation | Youth home-lessness & unemployment | Brotherhood of St Laurence (Education First Youth Foyers) | 2001 | 15 Foyers | All states & territories (except NT) | |

| Hands On Learning | Education | Save the Children Australia | 1999 | 95 schools | 1,500 each year | QLD, NSW, VIC, TAS |

| Men’s Shed | Men’s health | N/A | 2005 | 987 sheds | 150,000 a year | All states & territories |

| The Song Room | Education | N/A | 1999 | 1,564 | Average 15,000 a year | All states & territories |

** Number of times the initiative has been replicated at a new geographic location

*** Australian states & territories where the initiative has been replicated

Seven lessons and observations

1. The evolution of the seven ventures followed three basic phases on their replication journeys.

A shorthand description of the three phrases could be ‘community, consolidation and influence’.

- The community phase involved identifying a gap in provision in response to the needs in a particular community. The developed program or initiative is often iterated incessantly and experimented with extensively in the community.

- The consolidation phase includes an initial replication beyond the original geographic location. This was usually accompanied by a series of investments across areas such as strategy, operating systems and processes, fundraising, codification of approach and measurement of impact.

- The influence phase: Organisations realised that continuing to roll-out their model with new communities alone was unlikely to achieve their aspiration – it would take too long and/or be too difficult to fund. To bolster their replication efforts, they identified ways that their initiative could influence diverse stakeholders to help solve the underlying cause of the social issue they care about.

2. Diverse approaches were taken to social replication, with some pursuing multiple approaches in parallel.

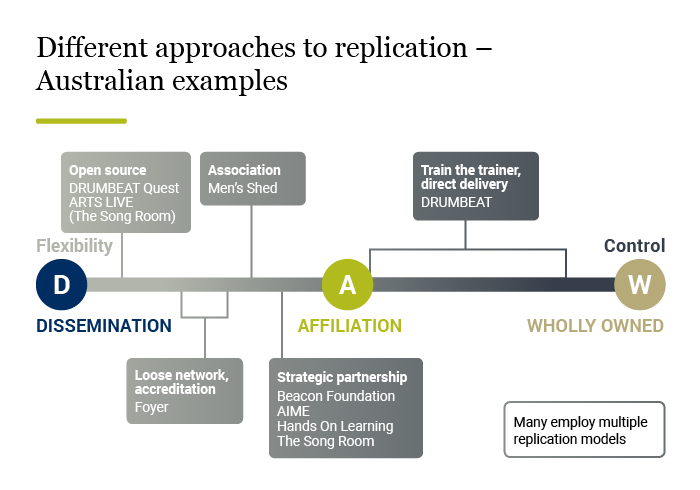

The ventures used different approaches to achieve replication, with some ventures using more than one approach (see Figure 2).

For example, the core operating model of DRUMBEAT, an evidence-based social and emotional learning program, is a ‘Train the trainer’ model with over 6,500 trainers in Australia and overseas. DRUMBEAT also provides direct delivery to schools and community organisations. In 2016 a digital version, DRUMBEAT Quest was released for children 8-14 years which is open source. A key element of the interactive computer game is the facilitated discussion that goes along with the game to embed and enhance the social and emotional learning.

3. All continued to use models of replication that retained significant control over their approach.

Although The Song Room and DRUMBEAT have developed a dissemination model, all ventures have a version of their activity that continues to exercise significant control over design and execution, with an ongoing relationship and an exchange of services in return for a fee or co-investment.

DRUMBEAT Quest, the digital version of DRUMBEAT can be classified as ‘dissemination’ on the replication spectrum, where the originator creates resources that enable an independent ‘other’ to implement the venture in a new location without any ongoing relationship. The Song Room developed a digital education program, ARTS LIVE, with 17,000 registered educators who can access resources independently in the classroom to teach arts learning.

4. All recognised the need to evaluate impact to tell their story to partners and supporters as they replicated.

AIME’s Founder/CEO Jack Manning-Bancroft was converted to the need to measure impact early in his journey to scale AIME: “We have to have numbers and metrics that track the impact so we can quantifiably show whether our intent actually makes a difference.”

But impact evaluation investment is kept at the minimum viable to deliver a strong message. The current shorthand ‘AIME Quick Facts’ (see right) covering three headline areas of impact was first introduced some five years ago. The dimensions refer to both the past and setting an ambitious vision of success for the future.

The innovative school retention program Hands On Learning is now part of Save the Children. It developed a monitoring and evaluation framework, in conjunction with Melbourne University, that aligned with their school partners’ needs and funding approval processes.

Both AIME and Hands On Learning brought recognised, external evaluators to design and implement periodic impact measurement so that the results message was objective and, so, more convincing. The external-led evaluative research of DRUMBEAT and Song Room included multiple peer-reviewed academic articles to strengthen their case, particularly to government stakeholders.

5. All developed a clear value proposition for implementers and communities who sought to replicate their approach.

Following good practice in licencing and franchising in the private sector, the ventures were careful to understand what services were required for a partner in a new location, the ‘implementers’, to set up the model or program.

Hands On Learning is a good example of a specific set of services provided to each school partner in return for co-investment by the partner school. This package includes support in recruiting the artisan trainers who implement the program, an immersion training for those trainers, expert shoulder-to-shoulder follow up support, and ongoing quality control and professional development. It also includes providing monitoring and evaluation data aligned to school needs and in time for school leadership to decide on the future year of funding for the Hands On Learning program.

…there is a natural decay in any licence or franchise relationship.

The service package and fee model needs to be dynamic, and responsive to the changing needs of the ‘implementer’ partner.

Robert Fitzgerald AM, long-term licence and franchise lawyer and SVA Board member, observes that there is a natural decay in any licence or franchise relationship; with a growing sense from the licensee or franchisee that they are able to work independently and avoid paying a fee to the licensor or franchisor.

In the social sector, the additional complexity or tension is that the originator isn’t driven by the profit motive. Instead, their social purpose motivates them to spread the successful program or approach for maximum social impact. The originator only charges a fee from the implementer in order to support further dissemination. Getting this balance right, between sustainability of the originator and support to the implementer, is a constant challenge.

The seven ventures have grappled with and modified their service packages over time.

Foyer Foundation works across a network of 15 integrated learning and accommodation settings, known as ‘Foyers’, which provide accommodation, personal development, and employability support in a safe and nurturing environment. The Foyer Foundation’s role is to innovate, champion system and service reform and ensure the Foyer network can deliver the best quality offer for young people. It has adapted its approach in Australia since the first Foyer was established in 2001.

Each Foyer location has a different set of partners and service offerings responding to the needs of the young people accessing the model. Even so, the Foyer Foundation has identified the opportunity to promote best practice across the Foyer network through accreditation of Foyer locations and a national community of practice. The Certificate 1 in Developing Independence for young people aged 16–25 who were at risk of, or experiencing, homelessness, was developed specifically for young people at the Education First Youth Foyers, providing an intentional partnership with the TAFE campuses where these Foyers are located.

Men’s Shed offers a package of services including vetting new sheds, guidelines and manuals, supporting start up via a mini call centre, group insurance and channelling services from other providers via the sheds (e.g. mental health). It charges a fee to its members but also secured a critical, recurring Federal Government grant to help cover its lean central operations.

6. All demonstrated an unwavering focus on purpose and quality programmatic delivery, usually in preference to financial sustainability.

Ventures maintained a strong focus on their mission and the quality of what they delivered in the community.

… but the risk of compromising quality and drifting away from the organisation’s mission was deemed too great.

This unwavering focus was maintained in the face of limited resources and the pressure many felt from funders to transition to a model that reduced reliance on philanthropy. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all successful ventures cited the persistent resource challenge throughout their scaling journey but they maintained their focus on high quality delivery within a tight budget well into the consolidation phase.

Hands On Learning requires ongoing philanthropic support to cover its operating costs. Social enterprise and fee-for-service models were considered but the risk of compromising quality and drifting away from the organisation’s mission was deemed too great. It wasn’t until the 17th year of operation that Hands On Learning decided to merge with Save the Children, in part to reach a more sustainable resource base.

In the case of Men’s Shed, it wasn’t until the number of member sheds already exceeded 300 before the organisation submitted a funding proposal to the Federal Government. Up until that point, the model consisted of quality support to members funded by members themselves and philanthropy.

The Song Room was considering pursuing an opportunity to scale its digital delivery platform internationally, yielding a new income stream. Instead, it decided to focus more keenly on its original purpose: to promote equity in education in Australia. As it approaches its 20th year in operation, its future focus is on partnering with state government departments of education to grow school capability and culture – an aspiration of systems influence explored below.

7. Most ventures have always had, or have developed as they replicated, an explicit aspiration to shift one or more of the underlying conditions in the relevant social service landscape.

Many of the ventures saw the limitation of how much impact their individual programs or initiatives could have. They realised that they needed to engage with the system to change not only the visible symptoms of a social issue, e.g. older men’s social isolation, but the underlying conditions that lead to those symptoms, e.g. employment norms and practices, lack of services to promote older men’s engagement with community, and society’s prejudicial views of older men as unproductive or unemployable.

The US not-for-profit FSG defines these underlying conditions as policies, practices, resource flows, relationships and connections, power dynamics and mental models.[3]

Endeavouring to change one of more of these conditions is often referred to as ‘systems change’. Most of the ventures reviewed have explicitly defined their aspiration as some level of systems change.

… seeking to harness the loose network of 15 Foyer locations… to drive a broader campaign for systems reform.

In 2016, Hands On Learning, took the decision to merge with the larger organisation Save the Children. In part this was to achieve greater financial sustainability. However, perhaps more importantly, the merger was pursued to overcome what Hands On Learning had identified as the [limited] ability, as a small organisation, to contribute to change beyond the close to 100 schools it had reached. With Save the Children, Hands On Learning’s voice is stronger in conversation with government, increasing the likelihood that its approach can inform policy, practice and resource flows.

In a different context, the Foyer Foundation is seeking to harness the loose network of 15 Foyer locations and a further five ‘Foyer-like’ operations to drive a broader campaign for systems reform. This reform would invest in young people’s talents, capabilities and aspirations and design service responses around these, rather than young people’s deficits, problems or needs. These reforms are driven through network enhancing initiatives including the accreditation scheme, community of practice and forums such as the annual Foyer conference.

In 2017, the Foyer Foundation entered into a strategic partnership with the national anti-poverty group the Brotherhood of St Laurence (BSL). This partnership enabled the Foundation to further expand the Foyer concept, leveraging the profile and extensive knowledge, research and service development expertise of BSL. Since 2013, BSL has been a key partner in three Foyer locations, under the banner of Education First Youth Foyer. BSL’s investment in evaluative research has enabled the most rigorous longitudinal evaluation of the Education First Youth Foyer model. This will inform the development of a national foyer evaluation, monitoring and impact evaluation, which will be rolled out across accredited Foyers. Their objective is to develop a response to youth homelessness, working with state and federal governments to understand and incorporate successful features of the Foyer model into policy and youth accommodation investments. The Tasmanian Government is transitioning all youth support housing services to the Education First Youth Foyer model and the Foyer Foundation is promoting a national response with a goal to have 30 accredited Foyers by 2030.

… realised that organic growth… would not allow it to reach its broader aspiration to contribute to solving inequity in the education system.

The Song Room’s CEO Simon Gipson describes how, after a decade in existence, the organisation reached peak direct delivery: an impressive 20,000 student participants per week and over 17,000 registered users on the digital platform ARTS LIVE. This scale then dipped to around 8,000 students per week owing to reduced Federal Government investment in the area. The organisation realised that organic growth, by partnering with individual schools as it had done since it started, would not allow it to reach its broader aspiration to contribute to solving inequity in the education system.

While direct partnership and program delivery remains a core activity for The Song Room, its deeper engagement with education departments targets the underlying challenge – developing school cultures that understand the importance of arts learning. According to Gipson, for the ‘big picture’ their focus is on professional development, student outcomes and supporting education departments to create learning models with resident experts to embed the approach beyond traditional arts and music subject matter. The intention is to influence not only policy, practice and resource flows, but also broader attitudes concerning arts education.

Summary takeaways

The experience of ventures that have succeeded in replicating for scale in Australia in recent years offers emerging lessons for aspiring founders, organisations, supporters and the social sector more broadly. The ‘how’ is important – identify and maintain a convincing value proposition, maintaining some measure of control over design and delivery, and measure and track just the essential.

… a good reminder never to forget to deliver on your purpose…

However, these lessons have largely been learned by private sector licence and franchise businesses and applied by the social sector. The ‘why’ is more interesting. Not only is there a good reminder never to forget to deliver on your purpose but that, even as a small organisation, you can aspire to contribute to broader social change. A number of the success cases reviewed demonstrate the potential for relatively small-scale ventures to influence the underlying conditions of the social sector in which they operate.

Author: David Williams

Contributors: Alison Kwok & Jessica Graham-Franklin

[1] Previously the International Centre for Social Franchising Toolkit

[2] Australia’s social purpose market, Centre for Social Impact, 2016

[3] The Waters of System Change, FSG, 2018

Some information related to AIME Mentoring and Hands On Learning has been updated since initial publication.