Paying what it takes to create impact

New research from SVA and the CSI has found that not-for-profit organisations across Australia are, in general, not funded for the actual cost of what they do.

- Not-for-profits, like all organisations, need to pay and support their staff. These costs are often broken into ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ costs based on how closely they are tied to on-the-ground projects.

- Many in the sector, NFP staff as well as funders, believe that the level of indirect costs reflects the efficiency or effectiveness of the NFP, despite growing evidence to the contrary.

- As a result, not-for-profit organisations across Australia are, in general, not funded for the actual cost of what they do. Funders cap their funding of indirect costs, and NFPs under-report their true costs. This leads to underinvestment and inefficiencies in NFPs.

- Solving this requires funders to be proactive in funding indirect costs, and reassuring NFPs of that so that they are told the true costs of running the project or organisation.

To deliver impact, a not-for-profit (NFP) must employ people, support them, and have the necessary infrastructure for them to work effectively. These costs have historically been separated out into ‘direct’ costs and ‘indirect’ costs based on whether they can be assigned to a particular project, even though they are all essential to creating impact. Indeed, indirect costs (or overhead) have become a fraught topic in the not-for-profit world. Some funders, donors, and even NFP staff view them as wasteful or unnecessary. Yet they are essential to running an effective organisation, and organisations that spend more on indirect costs are often more efficient, rather than less.1

Australia’s not-for-profit sector is vulnerable. The organisations that make up this sector, which together support millions of people every year, are often hindered by inadequate infrastructure and under-resourced central services. By one measure, Australian businesses spend twice the amount that NFPs do per employee on key capabilities such as training, information technology (IT), quality, and marketing. This leaves NFPs both less efficient and more vulnerable to external shocks. Funding the full cost of program delivery would allow NFPs to train their staff more effectively, have more efficient IT infrastructure, and report more accurately on their impact.

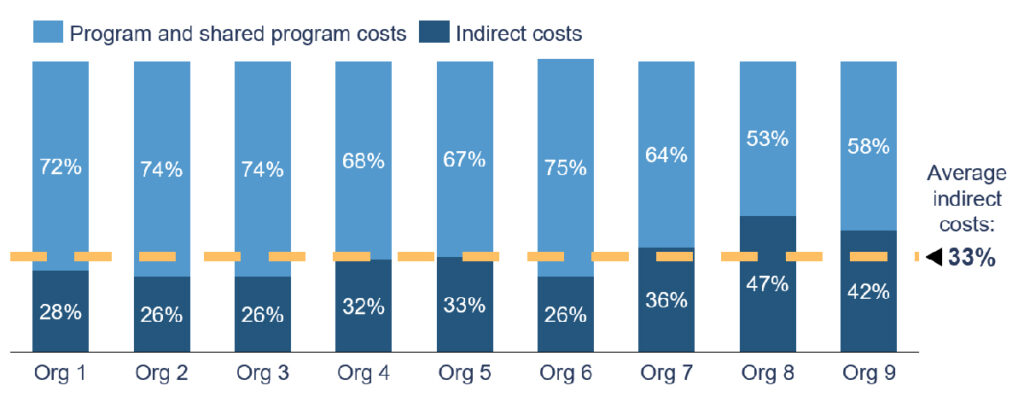

These NFPs had average indirect costs of 33% of their total expenses…

This far exceeded what is normally included in funding agreements.

New research, by SVA and CSI, shows the extent to which NFPs are underpaid for their indirect costs in Australia. Nine Australian NFPs, which ranged in size from $100m to $100k in annual revenue and worked across the arts, disability, and family services sectors, agreed to open their books for analysis. These NFPs had average indirect costs of 33% of their total expenses, with a range from 26% to 47%. (See Figure 1.) This far exceeded what is normally included in funding agreements (which generally range between 0% and 20%). This figure is also higher than what NFPs regarded as the maximum that philanthropy is willing to pay.

Government is the primary funder in the not-for-profit sector. However some philanthropic funders make significant contributions to this sector and have already started to solve the funding issue by creating trusted relationships and offering full-cost funding or untied grants. Yet more must be done on both sides to create a sustainable and effective NFP sector.

Perennial issue

The underfunding of indirect costs is not a new issue

As Jack Heath, CEO of Philanthropy Australia, says, funding difficulties have been a constant through his career. “In my 20 years of leading not-for-profit organisations, getting the true costs of delivering programs and services paid for has been a perennial problem.”

In the US, where tax laws and public attitudes have made this a significant issue, there have been campaigns to improve funding of indirect costs for three decades. US research has shown that one of the key drivers of NFP vulnerability is insufficient funding of NFP indirect costs. This is known as the ‘non-profit starvation cycle’ in which funders having inaccurate expectations of how much overhead is needed to run a not-for-profit leads to NFPs under-reporting their costs to funders. This creates a sector starved of the funding required to create resilient NFPs that can deliver long-term impact and address complex social issues.

Yet despite this problem being understood for many years, it remains unsolved. Progress has been made and US federal laws for minimum indirect costs enacted, but much work remains to change mindsets.

There has been far less advocacy on this issue in Australia, though it has been a topic of conversation in funding circles for many years.

What it means to pay what it takes

Part of the issue is defining what direct and indirect costs are. One way to think about direct costs is as costs specific to a project, i.e. costs that would not be incurred if the project did not exist such as service delivery staff and project expenses. Indirect costs, then, are costs that cannot be directly and easily attributed to a specific project. This includes finance, learning and development, IT, measurement and evaluation, and human resources.2 The concept seems straightforward, but which costs are considered ‘direct’ or ‘indirect’ can vary from organisation to organisation or from project to project within an organisation. For example, whether marketing costs are direct or indirect depends on to what extent they focus on a particular project, rather than the whole organisation.

To pay what it takes, then, is to fund the full cost of running a project including a share of the indirect costs that are needed to support it. Indeed, the entire idea of direct and indirect costs is a false dichotomy – every project requires both types of costs to be covered to succeed.

An undervalued necessity

Indirect costs have an image problem, to put it lightly. Funders (including the general public) will sometimes choose not to fund NFPs which have ‘high’ indirect costs. According to Genevieve Timmons, Senior Associate with the Alliances Portfolio at the Paul Ramsay Foundation, foundations find it a complex subject: “In my early work with foundations and philanthropic donors, people talked about admin costs as if they were an unnecessary impost, and not relevant to charitable activities. This view has run counter to their priorities and experience as high level business people, where investment in staff, infrastructure and research is recognised as essential to success.”

This attitude towards indirect costs is common despite significant evidence showing that indirect costs do not indicate the efficiency or effectiveness of an NFP.3 In fact, the opposite is often true. Spending insufficient resources on indirect costs has been shown to reduce overall NFP effectiveness.4 This is intuitive – an organisation that can invest in training its staff, building good financial systems, and measuring its impact is much better placed to be effective than one that cannot.

Levels of awareness can be starkly different according to whether you are speaking to staff, directors, or individual private donors.

Even where funders are willing to pay the full costs of programs, NFPs regularly under-report their indirect costs. There are strong and persistent beliefs about how much funders are ‘willing to pay’ for these indirect costs, and NFPs will undercut themselves to fit within this limit. This means that many funders are unaware that they are underpaying for indirect costs and therefore the true cost of a program.

Jack Heath notes how common this has been: “I’ve done the overheads dance. I’ve pitched funding proposals according to what we thought the funders would accommodate. I was even involved in a government funding process where, at the last minute, the minister’s office told us to remove the indirect costs from the program. And, in a desire to get the program funded, I said okay.”

Genevieve Timmons says that people’s understanding of this issue is also highly varied, even within philanthropic organisations: “Levels of awareness can be starkly different according to whether you are speaking to staff, directors, or individual private donors. It’s often staff that are already well down the track of understanding the need for indirect costs, and keen to have their board and donors move to the right side of history on this issue.”

There are many reasons that NFPs find it difficult to be honest about their indirect costs. The power difference between funder and fundee make it difficult for NFPs to have honest conversations about costs with their benefactors. The competitive nature of the funding environment means that NFPs are discouraged from revealing information they believe could be potentially damaging, even if it may lead to better funding arrangements. There are also significant reputational concerns about indirect costs, with media commentary often being highly negative.

Indirect costs are only used to assess and compare NFPs because of the lack of simple alternatives. Unlike for-profit businesses, whose performance can often be distilled to a set of financial metrics, not-for-profits resist easy comparison. Measuring the impact an NFP creates takes time and resources, and is often not comparable to the work of other organisations. The outcomes that funders and NFPs are aiming to achieve are also not always aligned. Hence the appeal and longevity of indirect cost measurement, an easily calculated number that seems to compare ‘efficiency’, even though we have known for years that it is unrelated to organisational efficiency or effectiveness.

How NFPs are affected

The funding of direct costs without indirect costs leads to what Jack Heath calls the “volcano funding approach”, where program delivery is funded but core costs are not: “It leads to organisations where the centre is hollowed out, but it’s built up around the edges. And, you know, volcanoes do two things: they blow up, or they go dormant”.

NFPs have been battling with this issue for so many years that it has become ingrained in their processes. This includes many NFPs creating deliberate inefficiencies to reduce the ‘observed’ indirect costs of a project.

NFPs named a number of harmful effects resulting from underfunding.

Firstly, front line staff do more administrative work as they can be considered a direct cost. This affects the structure of organisations.

Other costs will be shoehorned into direct costs even when not the most economical. According to the CFO of one large NFP, they use local suppliers rather than centralised services to maximise their ‘direct costs’, which has the effect of reducing their efficiency and ability to leverage economies of scale. “Potential benefits expected from scale and diversity are frequently eroded by funder approach to indirect costs. [My organisation] can be viewed as the aggregation of a large collection of local services, rather than a true national group benefiting from economies of scale and lower total delivery costs.”

… one of the strongest [effects] is long-term underinvestment in the areas covered by indirect costs.

Secondly, they have to spend significant time searching for funding to shore up existing programs. Every project that is not fully funded must have those costs supported from elsewhere, generally with untied funding (funding that is not restricted to a particular project or purpose). This type of funding is relatively rare and highly sought-after. But it creates further inefficiencies; effectively, NFPs must fundraise twice for every underfunded project, once for the direct costs and again to cover the rest of the costs. Ironically, this increases the NFPs indirect costs for fundraising.

The other effect and one of the strongest is long-term underinvestment in the areas covered by indirect costs. Compared to a selection of Australian NFPs, a corporate sector benchmark study suggested that businesses spent twice as much per employee on key capabilities such as training, IT, quality, and marketing.

NFPs called out three flow-on issues from these effects: there’s higher staff attrition due to low investment in training and staff mental health, limited ability to collaborate due to limited resources and time, and reduced strategy development and strategic capacity.

As explored above, NFPs underinvest for a number of reasons, including that their indirect costs are not fully funded, reputational concerns around indirect costs, and expectations around funder willingness to pay.

This not only decreases effectiveness, it increases risk as well – complying with regulations and funder requirements is, after all, an indirect cost.

What can be done

According to interviews with philanthropic sector leaders, philanthropic practice in Australia has started to shift.

Genevieve Timmons notes that a number of Australian philanthropic funders have begun to pay for the full cost of impact, with several focusing on how to support the whole organisation rather than just the project: “This is not a new concept – for some foundations, indirect costs have been part of the discussion for many years. For example, my work with the Portland House Foundation and Reichstein Foundation always had flexibility around support for indirect costs, based on recognition that our grant recipients could advise effectively on the best use of our funds. And I know of other colleagues for whom untied grants and negotiating financial support with their grant recipients has always included recognition of core and indirect costs. But this approach has not been the norm by any means.”

Indeed, there is not only one way to pay what it takes. There are a variety of ways to fund the full costs of organisations, including providing full-cost project funding, untied funding, or capacity-building funding. Which of these models is best depends on the goals of the funder and the sector/issues they focus on. By having honest conversations with NFPs, funders get a better sense of how they can best support the NFP’s work and create the most impact.

Convincing NFPs to be honest and open about their costs requires a significant level of trust in the relationship…

Even where funders are open to paying for indirect costs, they still need to ensure they proactively understand their fundees’ true costs and demonstrate willingness to pay what it takes. Otherwise, as mentioned above, it is likely that NFPs will continue to deliberately under-report their indirect costs.

As Jack Heath notes, convincing NFPs to be honest and open about their costs requires a significant level of trust in the relationship, otherwise they fear losing the funding. “We need to make an extra effort to create much higher levels of trust between non-profits and funders, so that we all feel comfortable having much more direct discussions.”

Part of this issue is a lack of good data. Funders are often unsure of the true costs of creating specific outcomes. NFPs can have a limited understanding of their own actual costs and how they should be allocated by project. A better understanding of cost allocation methods and better data on the cost of achieving outcomes will help to shift the power differential.

The public narrative about indirect costs also needs to change. The beliefs of the media and general public play a role here, often creating a situation where many people new to philanthropy or the NFP sector have a dim view of indirect costs that needs to be consciously reversed.

Indirect costs should not be associated with ‘waste’ in the minds of the public, of funders, and of NFP staff themselves. Spending donor money to have an accountant is not wasteful, it’s prudent. Spending donor money on a better computer system or more administrative staff increases efficiency and makes every dollar go further. NFPs need to have the freedom to balance their costs in a way that they believe creates the most impact. A range of activities and initiatives will need to be undertaken to change attitudes towards indirect costs more broadly.

What you can do

Philanthropic funders are invited to join a community of practice around paying what it takes, led by Philanthropy Australia. The purpose of the group is to share best practice and help philanthropic organisations to maximise their impact.

Download the full report, ‘Indirect costs in the Australian for-purpose sector – Paying what it takes for Australian for-purpose organisations to create long-term impact’

This work was supported by the Paul Ramsay Foundation and Origin Energy Foundation.

Contact us for more information about the report or ongoing work on this topic- Fiennes, C., Good charities spend more on administration than less good charities spend, Giving Evidence website

- This is a highly simplified explanation. For a more detailed definition of indirect costs and cost allocation methodologies, see the report.

- Caviola, L. et al, “The evaluability bias in charitable giving: Saving administration costs or saving lives?” Judgm Decis Mak. 2014 Jul 1; 9(4): 303–316.

- P. Rooney and Frederick, Heidi K., Paying for Overhead: A Study of the Impact of Foundations’ Overhead Payment Policies on Educational and Human Service Organizations, p. 36, 2007.