Seven pitfalls to avoid in outcomes measurement

What are the common things that go wrong when setting up an outcomes measurement approach? SVA consultants share 10 years of insights.

- In the last decade of working with a wide array of organisations, SVA consultants have seen where things can go awry when implementing an outcomes-focused approach – not just immediately but over the long term.

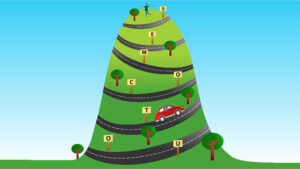

- We’ve identified seven common pitfalls ranging from the classic one of doing it because you think you have to, through the seemingly obvious one of leadership not backing it enough to simply giving up too quickly.

- The key takeaway is that to embrace outcomes measurement requires strong leadership, and the right structures, commitment and resourcing to build and sustain the new culture needed.

Over the past 10 years, we’ve seen many organisations start to implement an outcomes-focused approach – setting up the processes and systems to start measuring outcomes.

Some do this to tell the story of how their activities are changing the lives of the people they work with. For others, ‘managing to outcomes’ is the goal – testing, learning and iterating to make sure that services are effective. Some do it for both these reasons.

We’ve worked with many organisations, ranging from small social enterprises through to large multi-service providers, from community embedded organisations through to organisations which provide services on behalf of government, as they implement an outcomes-focused approach.

As a result, we’ve seen where things tend to go awry not just immediately but over the long term.

We have already covered the what, why and how of managing to outcomes and provided a detailed guide for developing an outcomes-focused approach with summary articles (How to adopt an outcomes-focused approach). In this article, we’ve outlined seven of the common pitfalls to avoid when adopting an outcomes-focused approach:

- Doing it because you think you have to

- Biting off more than you can chew

- Leadership isn’t behind it

- Thinking you can wing it

- Data is difficult to make sense of

- Ignoring the big picture

- Giving up too quickly

By avoiding these pitfalls, your outcomes-focused approach is more likely to hold, embed and grow, reaping the benefits that you seek: the potential to constantly improve what you do and provide improved outcomes for the people your organisation exists for.

1. Doing it because you think you have to

This is a classic pitfall. As governments start talking about payment for outcomes, and more philanthropic funders ask for evidence of results, organisations can feel pressured to implement some form of outcomes measurement system.

As a result, some organisations simply focus on proving the worth of what they do. Others do it to safeguard the funding they receive from government. Others still do it simply because the funder tells them to.

… they haven’t changed how they think about evidence or the data that they collect over time.

Any of these can result in organisations chasing their tails. Different funders may want to see different outcomes – and these can change. The result can be that organisations don’t actually understand what they are good at doing, and instead simply follow the money.

We worked with one organisation that thought they needed to gather outcomes data to win funding. The data began to show them how the changes wrought in one person – through the organisation’s activities – rippled out into their community. The broader outcomes data contributed to the organisation winning a large chunk of funding. Following this win, they opted not to investigate the data any further. As a result, they haven’t changed how they think about evidence or the data that they collect over time.

This was a lost opportunity.

For those that do it because they think they have to, it is inevitable that the organisation will lack the commitment required to successfully implement an outcomes-focused approach. It requires resources and for most organisations, a deep cultural shift.

Everyone has to adapt and adopt new ways of working. This can only happen if there’s a clear line of sight between doing it and improving outcomes for the people you are supporting or making a difference for.

2. Biting off more than you can chew

Some organisations start off with very big plans; they want to do everything. They expend a lot of time and resources in planning their outcomes-focused approach, defining the outcomes of all of the organisation’s activities or programs. They’ve worked it out on paper. But when they come to implement it, there’s too much to do all at once; it’s too complex.

… what’s needed is to stay focused on measuring what really matters.

These same organisations most often don’t have a culture of continuous improvement, of gathering data to learn from it. Changing the whole organisation’s culture at once is just too hard. They also haven’t worked out how all this new data will be incorporated into the way the organisation does business day-to-day, or how the data will be used in decision-making.

Instead, what’s needed is to stay focused on measuring what really matters. For larger organisations, while it’s good to get a read on what’s happening across the board, it’s better to focus on a discrete area for initial implementation – whether that’s by program or geography.

It’s better to start small at a level which feels comfortable for your organisation and recognise that you’ll build up. Be clear about the core questions and the core metrics that you want to focus on. Sticking to a small number means you avoid getting overwhelmed by the data and analysis burden.

3. Leadership isn’t behind it

Too often the champion for the new approach is just one individual, who has their work cut out trying to win and sustain the investment and commitment to the cultural change needed. Sometimes, the leadership pays lip service to the initiative.

Having a real and authentic commitment to measuring outcomes across the leadership team is imperative for the success of any outcomes-focused approach. It requires both a change of culture which needs to be led from the top, investment in resources and staff, as well as a commitment to use the data in decision-making.

You need to be sure that momentum for an outcomes-focused approach is not dependant on the enthusiasm or job role of one or even two people.

As much as possible, you have to protect yourself against significant future change in the organisation – whether that’s the CEO, another person in the executive team responsible for outcomes measurement, or a change in funding or strategic direction.

You need to be sure that momentum for an outcomes-focused approach is not dependant on the enthusiasm or job role of one or even two people. It needs to endure in the face of changing personnel and even organisational direction. Therefore, there must be a depth of commitment at the leadership level as well as the accountability structures that will support the initiative’s longevity.

4. Thinking you can wing it

It’s easy to think you can sort out resourcing and staffing requirements after the initial implementation.

Consider it as a journey, not a one-off purchase.

If you hire a consultancy like SVA to support you through the initial stages, it’s not obvious what you don’t know or what the internal capacity is to do the work. Once that support is gone, you need to have the committed resources to sustain the ongoing work and make the outcomes-focused approach sticks. Consider it as a journey, not a one-off purchase.

Too often the drive comes from someone who has simply shown the enthusiasm and interest, and when they leave, the system goes belly up. Other times it is from someone who has shown willingness, but doesn’t have the needed skills and experience to implement.

It requires a broad mix of skills from influencing others… through to data literacy,

What’s needed are dedicated resources internally; staff or volunteers with the skills, capabilities and authority.

It requires a broad mix of skills from influencing others (throughout an organisation) through to data literacy, analysis and reporting. Importantly, the function needs to be embedded in a role, with defined responsibilities and KPIs and supported by the organisational structure.

5. Data is difficult to make sense of

Too often people leave the question of how to bring data to life until the end of the implementation. However, questions about how data can be presented in appropriate and accessible ways are crucial for the success of any system. If the data isn’t used, and isn’t made part of the conversation, then you haven’t closed the loop and you’re not learning and improving what you’re doing.

Make sure you think about all levels of the organisation. Who needs what information to improve what they do? Make the data visual. Think about providing feedback to customers or clients, as well as to staff and funders. Let them know how things are progressing over time. Show the changes that have been made, and be transparent to maintain momentum.

You need to have a clear and pragmatic way of thinking about and assessing how your activities contributed to the outcomes…

When considering what the data means, be sure not to assume all the change is because of your work. This is the challenge of understanding your contribution. You need to have a clear and pragmatic way of thinking about and assessing how your activities contributed to the outcomes that people may have experienced.

Making sense of data can be complex. However, there are ways. There’s a spectrum of sophistication and rigour you can apply; looking at historical trends can shed light on these questions.

6. Ignoring the big picture

Too often leadership and even the outcomes lead underestimate the amount of change needed across the organisation to successfully implement this new approach. Focusing on measuring outcomes is a cultural change as much as installing a system for collecting data. Changing a culture requires training, and ongoing effort.

… or encouraging a culture of honesty and inquiry rather than sufficiency.

Many organisations underestimate this and approach it as a one-off implementation. It becomes a discrete project with a desired output at the end.

However, significant ‘cultural shifts’ are required. For example, seeing measurement as a way to improve programs rather than as an audit; or encouraging a culture of honesty and inquiry rather than sufficiency. Ideally an organisation would consider this ‘business as usual’ and embrace all the questions and difficulties that emerge throughout the design and implementation.

Part of considering the big picture is thinking about the information technology or systems side of things. This is commonly done too late.

There are a host of ‘outcomes measurement and management’ system providers, but you must consider existing systems and processes that you want to integrate with. It is important to remember that at the data collection end, simple technology that is easy to use will always work the best.

Which system you go with and how you collect data are important considerations, as is involving frontline staff early on.

7. Giving up too quickly

We’ve seen numerous organisations give up too soon saying it didn’t work, particularly when the organisation has gone in with an overly complex approach. Clearly, expectations were that things would change quickly. Often they weren’t able to put the time or effort in to review and work out what to adjust and evolve.

It’s good to remember that you are unlikely to get it right straight away. So be patient, and allow for time to iterate as you learn what does and doesn’t work.

The sooner you get results and make better management decisions, the sooner people will get behind it…

As we’ve said, implementing an outcomes-focused approach is a journey, not a one-off transaction or installation. It’s about changing behaviours and learning as an organisation how to do it as you go.

With big organisations, progress can feel slow. It takes time to turn big ‘machines’ around and can be years between key milestones or progress points.

Smaller organisations that are more nimble and can bring a singular focus to the exercise may find it a lot faster and easier. It is still important to have that ongoing improvement process embedded in how you drive the change.

The sooner you get results and make better management decisions, the sooner people will get behind it and help build the momentum. We all need small wins and positive reinforcement – this will help in not giving up too early.

There are many pitfalls to avoid when designing and implementing an outcomes focused approach. But they can be conquered by ensuring the right structures and leadership are in place from the start, and you take a long-term view about how to build and sustain a new culture within your organisation that embraces outcomes measurement.

Thanks to Mitch Adams, Nick Perini, Jon Myer, Anders Uechtritz, Anna Ashenden and Jonathan Finighan for their contributions for this article.