The power of articulating your story(line) of change

How we updated the theory of change for Joint Management on Gunaikurnai Country reflecting the evolving partnership between First Nations and state government partners.

- SVA, in partnership with First Nations consultant Nicole Cassar, reviewed the first five years of Joint Management between the Gunaikurnai people and the Victorian Government.

- The five-year review is centred around a powerful one-page visual – the ‘storyline’ – that Joint Management partners are each using to tell their own story of what they have learned over the past five years, and what matters most for the next five years.

- This is informing a new five-year strategic plan to align the work that they collectively do, towards their joint vision of Gunaikurnai people leading the care of their Country every day.

“Theory of Change. Can we maybe call it something a little less… corporate?” said Craig Parker from the Gunaikurnai Traditional Owner Land Management Board looking at me hopefully. We were enjoying the 2023 NAIDOC Community Day celebrations at the Knob Reserve in East Gippsland, a significant meeting place for the Gunaikurnai people.

It was also the setting for our spontaneous yarns with community members on what they thought about Joint Management. We were reviewing the first five years of Joint Management on Gunaikurnai Country, a partnership between the Gunaikurnai people and the Victorian Government to care for Country together. Supported by our First Nations consultant Nicole Cassar, a Gunditjmara, Wotjobaluk and Maltese woman, these yarns were to inform that review.

I’d just floated with Craig the idea of updating the original Joint Management theory of change as part of this review.

A short version of the backstory

The Gunaikurnai Native Title area covers roughly 10% of Victoria (see Figure 1).

Gunaikurnai culture is embedded in Country which is vital to Gunaikurnai identity. Caring for the diverse range of forests, lakes, mountains, seas, plants, and animals that make up Gunaikurnai Country is at the heart of feeling connected to Country. This caring for Country, and the Gunaikurnai people’s connection with Country, was traumatically disrupted through colonisation.

The first step in ‘making this right’ towards Gunaikurnai self-determination was the signing in 2010 of the Recognition and Settlement Agreement (RSA). This was between the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC), on behalf of the Gunaikurnai people, and the Victorian Government.

One of the outcomes of the RSA was the handing back of 10 parks and reserves to the Gunaikurnai people through Aboriginal title, to be jointly managed by GLaWAC and the state. (See Figure 2)

A new entity, the Gunaikurnai Traditional Owner Land Management Board (TOLMB) was also established to guide the development of Joint Management planning for these parks and reserves, and to coordinate the monitoring and evaluation of its implementation.

One of the first responsibilities for the Gunaikurnai TOLMB was to develop a Joint Management Plan1 for those 10 parks and reserves, in collaboration with its Joint Management partners.2

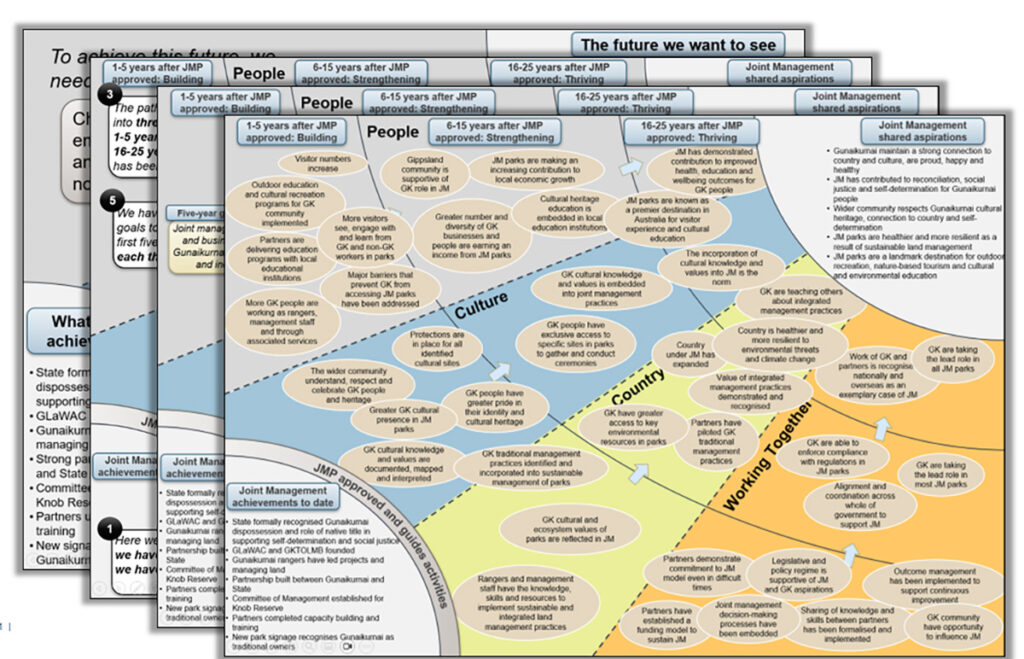

The Joint Management Plan included several pictures that were called the ‘theory of change’ (Figure 3). It reflected the commitment between Gunaikurnai people and the Victorian Government to work together to manage the designated areas on Gunaikurnai Country over the following 25 years.

It identified the most important changes, or outcomes, that partners wanted to see Joint Management achieve for People, Culture, and Country, through working together. It also recognised that the plan and the theory of change itself would evolve over time, incorporating knowledge gained through implementing the plan, as well as adapting to changes in the broader context.

Back to NAIDOC week in 2023

Five years on, a lot had happened in Joint Management. Despite the devastation of the 2019-2020 bushfires, followed by the pandemic, the Joint Management partners had together done a lot of what they said they would do in the plan. Though demonstrating their progress turned out to be tricky with a few too many outcomes and indicators to track.

A lot had happened more broadly too. The Yoorrook Justice Commission had started its work. Legislation advancing Treaty had been enacted by the Victorian Parliament. The Federal Government had committed to implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart. The Victorian Government had started handing back water to the Gunaikurnai community. Work had begun with the Federal Government to establish a Sea Country Indigenous Protection Area,3 together with other Traditional Owners. And the 2010 RSA that began the journey of Gunaikurnai self-determination was re-opened for negotiation, with an early outcome being the transfer of four new areas to Joint Management.

All these changes meant that it was time to update the theory of change. Or, as I replied to Craig, the storyline of why Joint Management exists and what it is here to do.

Why a storyline?

Stories are part of what makes us uniquely human. They are an essential way for us to understand who we are and our place in the world. They help us make sense of our past, navigate our present, and shape our future.

This is true for each of us as individuals.

It’s also true for each of the groups that we belong to. Stories connect us to each other, and form the heart of our culture.

But stories can disconnect us from one another too, especially when a story is told from only one perspective and affirmed as The Story.4

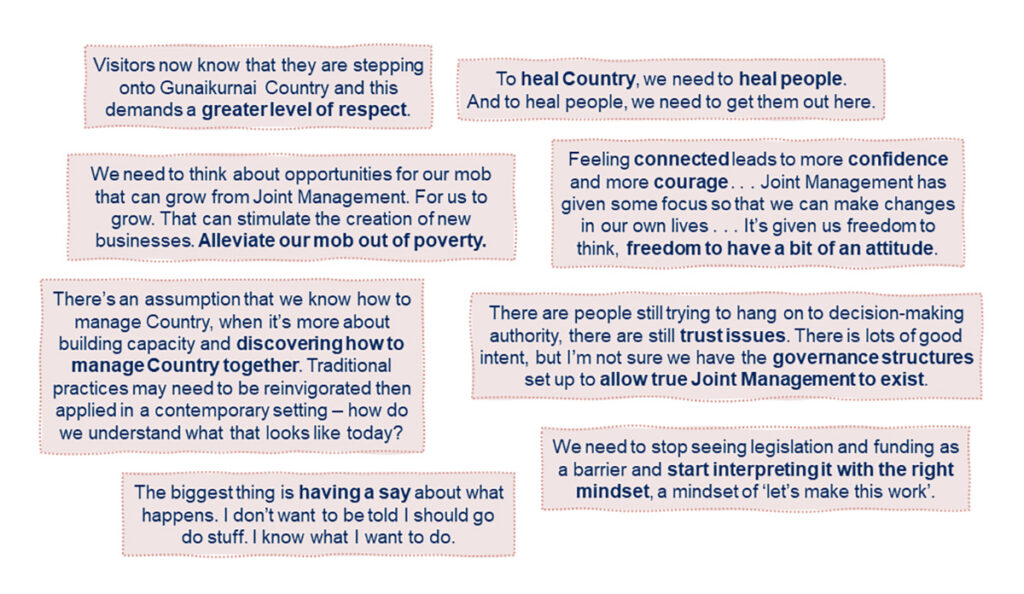

The Joint Management partners’ group contains the usual types of diversity that exist between individuals. It also contains strong cultural differences, both ethnic and organisational. And so we wanted to make sure that what we created was not a single story, but a guiding storyline.

We wanted it to be informed by as many different perspectives as feasible, and grounded in the knowledge that each person will have a slightly different understanding of what the words mean to them in their own context. A storyline that is just clear enough, and just flexible enough, that it resonates with each person working in Joint Management, no matter which partner they are with, no matter where they sit in the organisation, no matter how long they have been involved. A storyline that each person can – and will – then use to share their unique story of Joint Management with the wider community.

Crafting a new storyline

How we went about crafting a new storyline was just as important as the storyline itself. We spoke with almost 60 people across all levels in Joint Management partners and in community. And as we digested what people were sharing, in their own voices, we began to form a picture of what has changed over the past five years and the changes that matter most for the next five years.

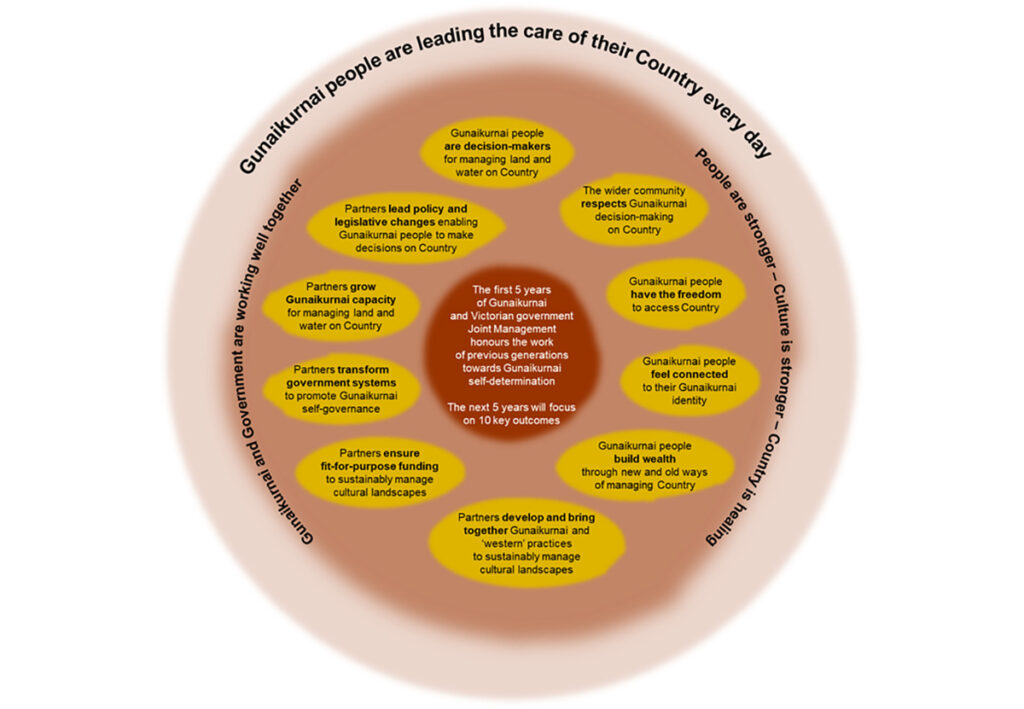

The storyline of Joint Management for the next five years builds on the original theory of change, with a few important differences (see Figure 5).

The most obvious difference is that it is now in a circular form. This visually reflects the gradual bridging between ‘western’ and Gunaikurnai worldviews among Joint Management partners. It portrays the inherent interdependence between the four themes and between the different outcomes. It also depicts the non-linear and iterative way in which change happens.

The centre honours where we have come from and points to the 10 key outcomes partners are collectively focusing on for the next five years, on their way towards their aspirations for People, Culture, Country, and working together, and their vision of Gunaikurnai people leading the care of their Country every day.

They reflect the increasingly shared understanding between partners of the evolving boundaries of Joint Management…

This new storyline is also less busy. The maturing of the partnership over five years means that each partner is comfortable with less being more. The work of Joint Management encompasses much more, of course, than the 10 outcomes highlighted in the storyline. What the storyline does is to help partners focus on the changes that matter most for the next five years.

Looking more closely, you’ll see that the words are subtly different. They reflect the increasingly shared understanding between partners of the evolving boundaries of Joint Management, towards the decolonisation of the way that Gunaikurnai people care for Country, and the bigger change of Gunaikurnai self-determination, for which Joint Management is one vehicle.

The findings from the five-year review that are captured in the storyline have not been shocking or surprising to people working in Joint Management. And yet there is something about naming all these things, about articulating them visually, that has turned out to be a powerful tool for aligning everyone involved and for communicating more broadly.

It is being translated into a strategic plan, with an indicator or two to track progress towards each outcome from year to year. It is being used to define principles to guide how partners will work together to implement Joint Management for the four new parks. It is being used to write the next chapter in Joint Management between Gunaikurnai people and the Victorian Government, and we look forward to discovering what happens next.

- The Joint Management Plan was the first of its kind in Victoria and was approved by the Victorian Minister for Energy, Environment, and Climate Change in September 2018.

- GLaWAC, the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (now the Department of Energy, Environment, and Climate Action), Parks Victoria, and the Knob Recreation Reserve Management Committee.

- Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation, Sea Country, GLaWAC website, n.d., accessed 5 July 2024

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, The danger of a single story, TED talk, ted.com, July 2009, accessed 5 July 2024