Why economic recovery relies on charities as a strong industry

Charities play a critical role in supporting and strengthening people and communities in Australia, but they also have a crucial role to play in Australia’s economy and its recovery from the impact of Covid-19. Suzie Riddell explains.

- Charities employ more than one in 10 workers in Australia – more people than mining and manufacturing combined.

- A thriving charitable sector is essential to our recovery from the Covid-19 crisis. It will help improve the economic productivity of the country as well as the wellbeing of communities and individuals.

- Sectors with high concentrations of charities – health care and social assistance, and education and training – are two of the three sectors expected to contribute the most to jobs growth in the next five years. These sectors also disproportionately employ women, who as a cohort have been hit hard by the crisis.

- Our analysis shows that while the JobKeeper payments are helping to support charities income and workforce for now, it is only temporary and there are other steps governments should take to help charities evolve their operating models, partner more effectively with other charities, and make better use of technology as well as improve their impact measurement.

- Are the charities you work with, fund or support ready to thrive in a post-Covid world?

We don’t often talk about the critical role of charities in Australia’s economy.

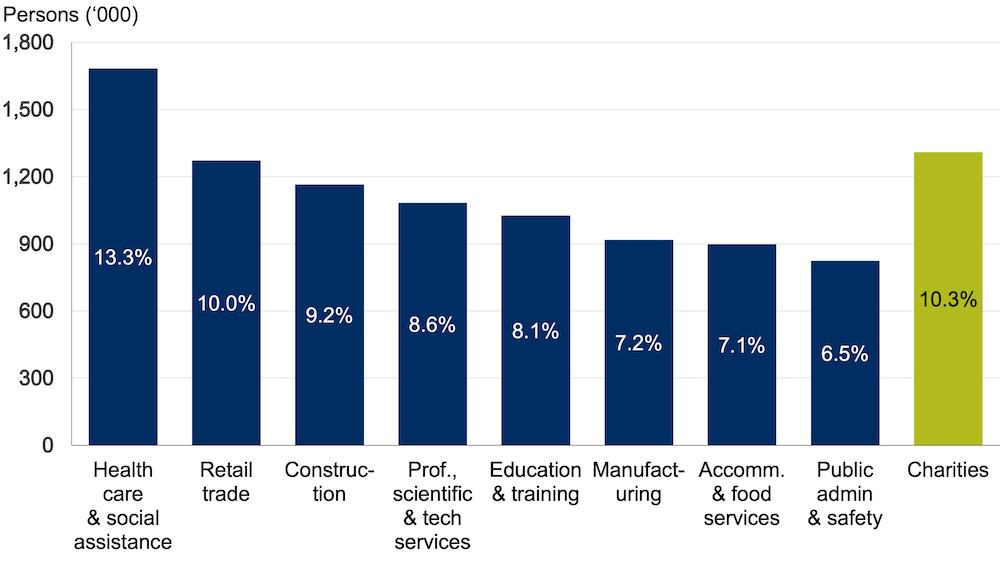

However, charities’ total economic contribution is equivalent to 8.5% of Australia’s GDP, and they employ more than one in 10 employees in Australia – 1.3 million people. That’s around the same number of people as retail trade (10.0% of people employed, our second largest employing industry after health care and social assistance), and more people than the construction (9.2%), professional, scientific and technical services (8.6%) and manufacturing (7.2%) industries.

Right now, the Australian economy is in trouble. Unemployment and underemployment are high, GDP is falling, and government budgets are under pressure. The Commonwealth Government has been clear that it sees employment as the key to a return to economic growth. As a major employer, charities will be a key part of the solution.

Investing now will not only sustain the sector, it will create employment and lead to a more resilient community in the future.

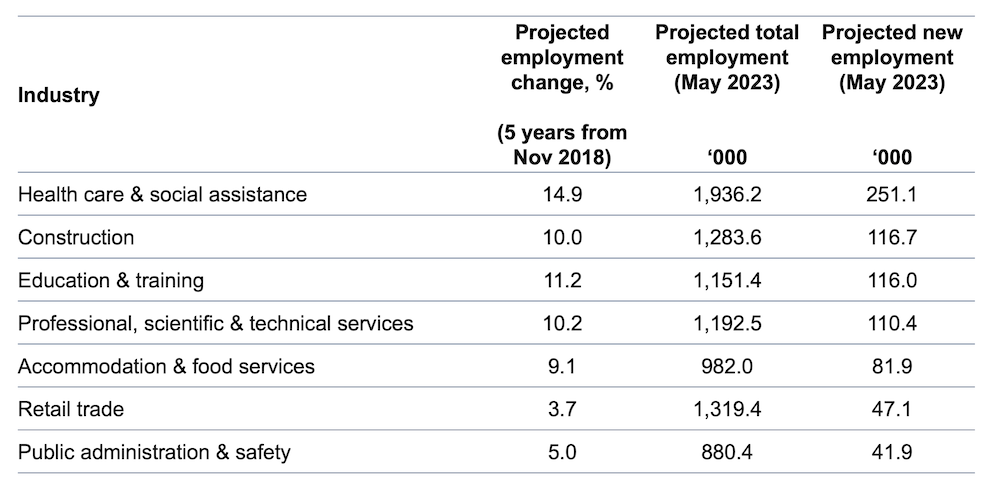

The types of jobs that charities offer are also going to be critical to economic recovery. Sectors with high concentrations of charities – health care and social assistance, and education and training – are two of the three sectors expected to contribute the most to jobs growth in the next five years. These sectors also disproportionately employ women, who as a cohort have been hit hard by the crisis.

This article takes a deeper look at the charities sector’s contribution to the economy and at the labour force engagement within the sector, building the case that investments in charities will form a critical part of the plans for Australia’s economic recovery.

Our analysis shows that while the JobKeeper payments are helping to support charities income and workforce for now, it is only temporary and there are other steps governments should take to help charities evolve their operating models, partner more effectively with other charities, and make better use of technology as well as improve their impact measurement. Investing now will not only sustain the sector, it will create employment and lead to a more resilient community in the future.

Charities as community infrastructure

We are all familiar with the critical role that charities play in supporting and strengthening Australia’s communities; they are key infrastructure in the fabric and functioning of society.

Charities provide vital services right across the Australian community. We rely on them for our education, health care, sports and recreation, legal services, employment services, religious activities, arts and culture, animal protection, aged care services, environmental protection and many other services and supports. Almost half of the charities registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) report that their main beneficiary is the general community in Australia.1 Without charities, our quality of life would be much poorer on almost every dimension.

For many years, Commonwealth, State and Territory governments have also relied on charities to deliver services on their behalf – from disability services to aged care to early learning. In aggregate, charities receive nearly half their income from governments.2

Charities also fill in gaps in the system. Within the community sector, the top three reasons for accessing charity services, as identified by sector staff, are affordability and costs of living pressures (81%), housing pressures and homelessness (74%), and inadequacy of income support payments (69%).3 This need is likely to be even greater during times of crisis and recovery, which will increase demands on charities.

Charities as critical in Australia’s economy

However, we don’t often talk about the sector’s critical role in the Australian economy.

Charities add around the same value to Australia’s economy as retail trade and employ more people than mining and manufacturing combined. The sector is an essential contributor to the Australian economy.

Charities closing their doors and shedding staff will damage our economy and our labour market at a time when we can least afford it. Charities which are able to keep their staff will not only be able to meet increased need for services that we expect to see during bad economic times, but also ensure employment for a significant proportion of the Australian labour force.

The modelling that SVA and the Centre for Social Impact (CSI) have conducted since the announcements of the extension of the JobKeeper payments shows it will have a positive impact on retaining jobs in the sector. But, even with JobKeeper, 170,000 jobs could still be lost by September 2021 and that’s assuming a gentle economic recovery which is by no means guaranteed. For more details, see Taken for granted? Charities’ role in our economic recovery.

Economic contribution

The direct economic contribution of charities is equivalent to 4.8% of Australia’s gross value added ($71.8 billion in 2014-15).4

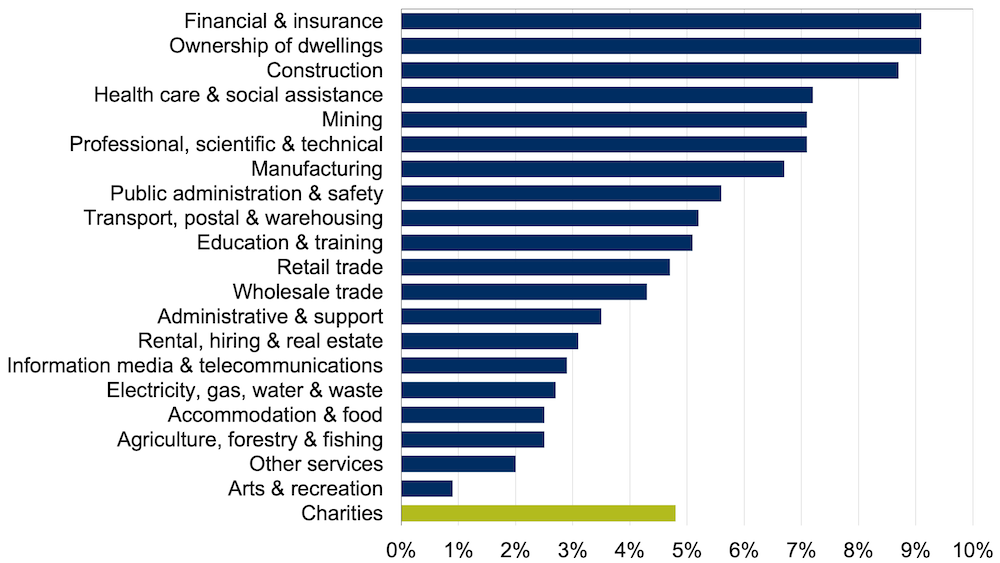

While charities are dispersed throughout various industries, comparing the charities sector’s size to key industry categories gives an indication of its relative importance to our economy. As Figure 1 shows, the charity sector’s direct value add is approximately equivalent to that of the retail trade industry (4.7%), and more than nine other industries.

Industry data is percentage of GVA at basic prices, current prices, June 2015, from ABS (2019) 5204.0 Australian System of National Accounts, 2018-19. Table 5. Charity sector data from Deloitte Access Economics (2017) Economic contribution of the Australian charity sector, direct economic contribution of the charity sector as equivalent share of Australia’s GVA, 2014-15.

If their flow-on contribution is also factored in, the total economic contribution of the charity sector in 2014-15 was equivalent to 8.5% of Australia’s GDP.5

The economic contribution of charities is in effect higher than this data suggests, because unlike many other industries, charities also leverage the time and effort of volunteers. In 2018, 3.7 million people volunteered in registered charities across the country.6 In 2014-15, the value of volunteer labour to the charities sector was estimated as $12.8 billion in terms of their cost in wages to hire, if paid.7

Labour force engagement

Beyond their general economic contribution, the role of charities as employers is critical in the current economic climate. The charity sector employs 1.31 million people – or one in 10 workers in Australia.

Again, mapping the employment share of the charities sector as a whole against Australia’s largest employing industries, as shown in Figure 2, demonstrates the scale of its contribution. The charity sector employs around the same number of people as our second-largest employing industry – retail trade (10.0% of people employed). It employs more people than the construction (9.2%); professional, scientific and technical services (8.6%); and manufacturing (7.2%) industries. Charities employ five times as many people as the mining (2%) industry.

Industry data is 4-quarter average ending February 2019, from Vandenbroek, P. (2019) Snapshot of employment by industry, 2019 FlagPost Blog, 10 April 2019, Parliamentary Library of Australia. Chart shows all industries employing more than 6% of the workforce. Charity sector data is AIS 2018, from ACNC (2020) Australian Charities Report 2018.

Even looking at the largest employing industries shows the importance of charities as employers. Health care and social assistance is the largest industry in Australia by share of people employed (13.3%), and education and training is the fourth largest (8.1%). Many of these employees will be employed by a charity.

Gender lens

Emerging evidence suggests that women have been disproportionately affected by the current crisis across many dimensions, including employment.

This impact could be even worse if charities are forced to shed workers. Looking at the 10 largest employing industries in Australia (Table 1), the two that employ a much larger share of women are both sectors in which charities are large employers.

Twenty-two per cent of all employed women work in health care and social assistance, compared to only 5.4% of employed men. Education and training employs 12.4% of all employed women, compared to 4.3% of all employed men.

In contrast, the three sectors with a disproportionately large share of male workers – construction; manufacturing; and transport, postal and warehousing – do not have many charity sector employees.

Table 1: Australia’s 10 largest employing industries, by sex

SVA and CSI analysis of Vandenbroek, P. (2019) Snapshot of employment by industry, 2019 FlagPost Blog, 10 April 2019, Parliamentary Library of Australia. Highlighted industries are those with a greater than 5 percentage point difference between their share of male employment and share of female employment. Data is 4-quarter average ending February 2019.

Sources of new employment

Charities are also major employers in many areas where we expect growth in service demand in coming years, such as aged care, disability services, education and health.

As Table 2 shows, health care and social assistance, and education and training, are expected to be two of the largest sources of new employment in the coming years. Growing labour market demand in these sectors could be a major force for job creation for those who need it most, if charities are thriving.

SVA and CSI analysis of Australian Government (2019) Australian Jobs: Jobs by Industry, Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Table shows all industries projected to add more than 40,000 new jobs between November 2018 and May 2023.

The cost of unresolved social issues

The risk that so many charities either decrease, stop services or fully close their doors begs the question, at what cost? The costs of social dislocation and not intervening early are already staggering.

The increase in demand for services and lack of capacity of charities to answer demand will further increase the financial stress for governments.

Australia spends $15.2 billion each year because children and young people experience serious issues that require crisis services. This figure includes annual costs of late intervention in Australia of $5.9 billion for child protection, $2.7 billion for youth crime, $2 billion for youth unemployment, $1.5 billion for youth and adult justice, $1.4 billion for youth homelessness, $1.3 billion for mental health, $1.1 billion for physical health, $0.3 billion family violence.

The average person who is experiencing homelessness costs the government $25,615 per year, totalling to almost $3bn per year (based on 116,000 people experiencing homelessness on census night in 2016).

Mental health services already cost Australia $9.9 billion a year.8 And poor educational performance and educational inequity directly affects long-term GDP growth. The fall in school performance in the 2009-2015 period in Australia was estimated to have cost us $118.6 billion, of which $20.3 billion was due to the increase in inequality (students in the bottom fall more than those at the top).

Add to these costs the social dislocation because of the implications of Covid-19. A recent study using Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) found that approximately 3.5 million Australians (or 28% of all workers) are employed in hard-hit industries such as store-based retail, tertiary education, mechanics and motor vehicle retailing, and accommodation. Additionally, 17% of people aged 15-66 live in a household in which the main earner works in one of these industries.

Women are also more affected, representing 53% of people working in primarily affected industries. Young people, people who rent, live in poverty, experience financial stress, or experiencing mental ill-health are more likely to work in these industries and be affected.

These individuals are likely to turn to charities for support. Indeed, demand for charity services has increased dramatically since March 2020 (see the first report in our Partners in Recovery series).

The government is already incurring large costs of unresolved social issues and these costs are on the rise. Since before Covid-19 charities were struggling to meet the needs across communities. Charities will be critical in rebuilding Australia’s economy and society to support the country not just to survive but to thrive.

Implications for recovery

The Covid-19 crisis has shaken the charities sector and the livelihood of many beneficiaries, clients, employees and volunteers. Charities are managing the confluence of service disruption, falling income, rising demand and higher operating costs.

Before the crisis, charities were operating on increasingly thin margins, and don’t have a big buffer of reserves to draw on. They face many financial constraints specific to their regulatory, operational and cultural environment. We know that charity revenues don’t recover from downturns the same way that business revenues do, and they can’t easily access the resources they need to rebuild and transition to a new normal (see the second report in the Partners in Recovery series).

The impact on individuals who have lost jobs, and on their families and communities, will be devastating and has the potential to cause long-term scarring.

Charities are responsible for delivering many essential services on behalf of Commonwealth, State and Territory governments. People and communities rely on these services, which would be compromised if charities are no longer viable. Charities are also a critical source of support for vulnerable members of our community, and we are already seeing larger numbers of people requiring such support as a result of the crisis. The demand for support is likely to remain high while the economy is recovering.

Even if the health crisis recedes in coming months, the Australian economy will take a long time to return to its previous position.9 The impact on individuals who have lost jobs, and on their families and communities, will be devastating and has the potential to cause long-term scarring.

It’s important to recognise that in aggregate, charities spend 55% of their expenses on employee costs,10 so support for charities translates very directly into money in the pockets of workers, which will be spent in a recovering economy.

A thriving charitable sector is essential to our recovery from the Covid-19 crisis. It will help improve the economic productivity of the country as well as the wellbeing of communities and individuals.

As a result, we are calling for the following:

- Create a Charities Transformation Fund to transition organisations to the ‘new normal’. Most charities do not have much financial margin or flexible untied funding, and so are unable to invest in capacity building and organisational transformation to prepare themselves for the post-crisis world – such as the ability to work and deliver services online, develop a new business strategy, invest in staff capability, bring back volunteers, or support mergers of multiple charities. Charities could apply a mixture of funding and capability building support.

- Monitor the impact of the JobKeeper ramp-down, and be prepared to extend and/or alter the policy settings if needed to provide ongoing support for charities, and minimise negative effects on the broader Australian community.

- Retain JobSeeker and other payments at a higher level to mitigate the increase in service demand on charities while also stimulating the broader economy.

- Maintain and, where needed, increase funding for government contracted services delivered by charities. Charities provide vital services on behalf of governments (including in early learning, aged care and disability services). Service funding for charities should reflect the true cost of delivering services for impact and meeting increased service demand, particularly given the sensitivity of the sector to changes in government funding.

- Make fundraising and philanthropy simpler to encourage increased giving. Creating nationally consistent fundraising regulations would reduce the red tape burden on charities seeking to fundraise in a changed environment.

- Support further research to better understand how to build back the charities sector so that they are funded for impact. Understanding the financial viability and business models of charities and how this might be reshaped in the future to ensure charities don’t just survive but are able to deliver the public good purpose for which they exist. There is also an opportunity to invest in systems to enable charities to measure outcomes more effectively, which will help governments, philanthropists and charities prioritise more impactful approaches.

We all need Australia’s charities to make it through to the other side of this crisis in a financially viable position, and in the long run to be more financially sustainable than they came into it. Our economy and our communities depend on it. Governments, philanthropists and charities need to work in partnership to ensure that this happens.

JobKeeper alone will not be enough to ensure the viability of the charity sector – in too many cases it is only delaying the inevitable. Now is the time to undertake the structural reform that the charity sector needs to thrive. It makes no sense to treat the sector that employs one in 10 of the Australian workforce as an afterthought.

These insights are taken from the report: Taken for granted? Charities’ role in our economic recovery, the third report in the Partners in Recovery research series by SVA and the Centre for Social Impact.

Author: Suzie Riddell

1. ACNC (2020) Australian Charities Report 2018. When charities report to the ACNC they must identify one or more groups of people as their ‘main beneficiary’.

2. ACNC (2020) Australian Charities Report 2018.

3. Cortis, N. & Blaxland, M. (2020) The profile and pulse of the sector: Findings from the 2019 Australian Community Sector Survey. ACOSS.

4. Deloitte Access Economics (2017) Economic contribution of the Australian charity sector.

5. Ibid

6. ACNC (2020) Australian Charities Report 2018.

7. Deloitte Access Economics (2017) Economic contribution of the Australian charity sector.

8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2020) Mental health services in Australia.

9. Reserve Bank of Australia (2020) Statement on monetary policy – May 2020; Daley, J., et. al. (2020). The Recovery Book: What Australian governments should do now. Grattan Institute

10. ACNC (2020) Australian Charities Report 2018.