Why STEM practices should be taught across the entire curriculum

- There is a considerable gap in resources and achievement levels within schools from different socio-economic communities, and STEM is at risk of becoming a source of even greater inequality in education.

- The report, STEM Education for all young Australians, commissioned by Social Ventures Australia in partnership with Samsung Electronics Australia and authored by University of Canberra Centenary Professor Tom Lowrie, calls for an approach that actively responds to the needs of children and their communities.

- To do this, Australia needs to teach the STEM practices that underpin STEM, rather than focus on content knowledge.

- This approach means students see STEM in action in day-to-day situations, and schools do not necessarily require extra resources.

STEM education will play a crucial role in preparing both individuals and Australia’s economy for the future. Accordingly, STEM education is currently undergoing extensive policy reform and significant public attention. Education needs to change in order to realize the vision of a highly diverse, creative, and sufficient STEM workforce. PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates if Australia were to shift just one per cent of its total workforce into STEM roles, it would add $57.4 billion its GDP.

While it is widely accepted that STEM skills are critical, there is even more urgency in disadvantaged communities. Australia must engage all students as we push to improve, focusing on students experiencing disadvantage and under-represented groups who are most at risk of being left behind, to ensure that all Australians can engage in rewarding STEM careers.

… STEM is at risk of becoming a source of even greater inequality in education.

Currently students in disadvantaged regions are achieving lower results in national and international testing. By the age of 15, these students can be up to five times more likely to be low performers than a student in a higher socio-economic area. Poor performance in STEM doesn’t just affect the fundamentals of the economy. It also limits social mobility. There is a considerable gap in resources and achievement levels within schools from different socio-economic communities, and STEM is at risk of becoming a source of even greater inequality in education.

How to improve STEM education in Australia

STEM Education for all young Australians (The paper), commissioned by Social Ventures Australia in partnership with Samsung Electronics Australia and authored by University of Canberra Centenary Professor Tom Lowrie, says we need an approach that actively responds to the needs of children and their communities.

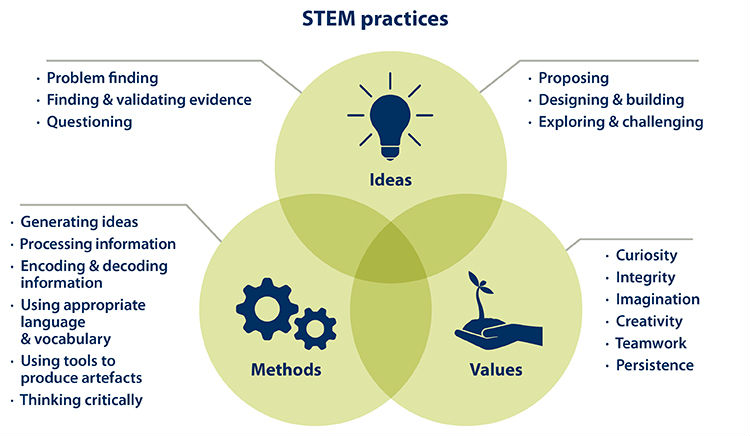

To do so Australia needs to teach the STEM practices that underpin STEM, rather than focus on content knowledge. That is the use of an idea, method, and value to achieve something.

STEM no longer refers to science, technology, engineering and mathematics as stand-alone subjects, but as an integrated approach to teaching the general capabilities on which STEM education is founded.

A practical example of this type of learning in a classroom might be a group of students designing and developing a community garden. Along the way they’ll apply the STEM practices they need, combining designing and building, generating ideas, and teamwork to complete the task and along the way learn STEM content and think about the broader context like the environmental or social impact.

… our rapidly changing world will require citizens to move across traditional domains.

“We argue that an increasing number of professions will require such knowledge into the future, however this knowledge will not remain specialised or localised within disciplines,” Lowrie says.

“As such, our rapidly changing world will require citizens to move across traditional domains. The specialised content knowledge will always be essential to some professions, but occupations we have not yet conceived will require very different practices.”

Research carried out by the STEM Education Research Centre found that student-led enquiry-based STEM learning, led to better education outcomes for primary and secondary school students, when compared to a content-heavy approach. While that study also saw students supported by digital tools, a STEM practices approach does not rely on or require any additional resources.

By teaching STEM practices content knowledge naturally flows, not just in the STEM discipline areas, but all curriculum areas including English, languages, and social sciences. The paper includes a National Framework for STEM education, which would include STEM as a general capability in the National Curriculum.

Importantly, this method does not require teachers add new content, and in turn put them under additional pressure. Instead teachers are encouraged to highlight the importance of STEM and ensure STEM learning occurs across all subjects.

By focusing on capabilities, rather than content, such a framework addresses concerns of teachers. These might include ‘I’m not a STEM teacher’, ‘The curriculum is still discipline-based’ and ‘you cannot assess STEM’.

A STEM practices approach recognises this and grounds learning in real-world skills while focusing on the underlying practices of STEM.

Successful STEM education considers the student first and what they need to live in their world.

“Teachers start with the unique needs of each community, which means students can see STEM in action in day-to-day situations,” Lowrie says.

“They can see that they can actively contribute to the future of their community in a meaningful way. School education needs to be responsive to these needs and prepare children for the future they will live and work in.”

A STEM practices approach recognises this and grounds learning in real-world skills while focusing on the underlying practices of STEM.

Spatial reasoning is a way of thinking that promotes STEM practices

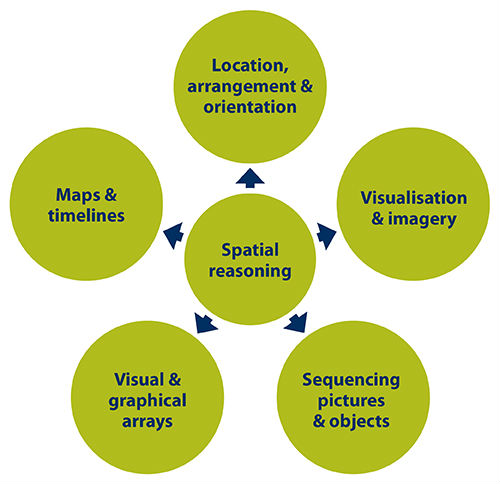

Spatial reasoning skills – which include our ability to locate, orientate and visualise objects, decode information graphics, and to draw diagrams – are used in everyday situations like driving, reading maps, and understanding structures. Good knowledge of spatial reasoning has been associated with a higher likelihood of STEM careers and a higher chance of success in those careers.

Spatial reasoning can be taught as a STEM practice across the humanities and social sciences by exploring maps, and pictures. Grade eight students could represent geographical data, conduct field sketches and create diagrams, with and without the use of digital and spatial technologies. This is a great example of how STEM practices does not necessarily require access to extra resources.

Examples of spatial reasoning can be found across all areas and all stages, of the curriculum, Lowrie says.

“This is one of the advantages of teaching STEM practices rather than STEM content; teachers do not have to feel concerned about making links to the curriculum, or missing content.”

STEM outcomes and disadvantage

The paper reflects what we’ve observed at SVA in our work across the education system. All schools need to ground STEM teaching in methods that actively respond to the needs of children and their communities. But this is particularly important for schools serving communities experiencing disadvantage. These students are less likely to have been exposed to STEM careers or mentors. STEM teaching must be linked to their lives, show them what a STEM career might look like, and connect them to STEM mentors within their communities. A school-wide approach increases the likelihood that all children will participate.

… the outcomes are allowing students to develop practices that involve saying, doing and relating.

Lowrie says this results in a sustainable approach to improving STEM outcomes that does not rely on extra funding, external resources and knowledge, which schools in communities experiencing disadvantage might struggle to access.

“Key outcomes are not about how much knowledge about science, technology, engineering and mathematics a student can reproduce on an exam paper,” Lowrie says.

“Rather, the outcomes are allowing students to develop practices that involve saying, doing and relating.”

Best practice in The Connection schools

The disparity in outcomes between students from communities experiencing disadvantage and their peers is the very reason SVA created the Bright Spots Schools Connection (The Connection). We partnered with Samsung Electronics Australia to create the STEM Learning Hub, an initiative that aims to improve STEM education opportunities for disadvantaged students. Consistent with our commitment to evidence-informed policy, the paper provided The Connection schools with validation that the enquiry-based, student-led, learning they adopted, is in line with best practice for improving STEM outcomes.

Victoria’s Sunshine College principal Tim Blunt has formally been grappling with the concept of STEM practices since 2010, albeit under another name. During a proposal for the funding of new facilities, Blunt was required to communicate a vision for the future of teaching at Sunshine. In that proposal Blunt outlined a focus on research and development – what he now understands to be STEM practices. That idea was refined through Sunshine College’s participation in the STEM Learning Hub.

“The report really vindicated the approach we’ve been taking at Sunshine College,” Blunt says.

“The way we’ve talked about it is applied learning. You try and develop enquiry. You try and develop the student’s ability to learn from one another. We have a team of teachers looking at open-ended questions for kids to delve into.”

We’ve got rid of textbooks… to show the staff that we don’t need to be hung up on content,

Of course, the benefits conferred from such an approach are contingent on a willingness on the part of school leaders to move away from traditional content-heavy teaching.

“The paper really validated what we’ve been doing for a while. We’ve got rid of textbooks, especially in the junior years, the reason for doing that was to show the staff that we don’t need to be hung up on content,” Blunt says.

“The challenge for some schools is whether or not they support that philosophy. In the junior years, content needs to take a backseat to developing skills.”

Examples for teachers willing to change

Like Sunshine College, another Connection school, Prospect North Primary School in South Australia, has been working to improve STEM outcomes with an approach that mirrors Lowrie’s STEM practices.

Marg Clark, the principal of Prospect North, regularly engages with other schools as a ‘lead learning site’ in the South Australian education system. She says the paper sets out why STEM outcomes are important, and how STEM practices can be implemented, in a way that’s accessible for all educators.

Prospect North Primary School looks at STEM with capabilities in mind. Junior primary school students are managing a large garden, where they spend a lot of time investigating, collecting data on rainfall, soil quality and temperature. They’ve built a pond and are studying frog life cycles. Students aren’t sitting in a class learning about frogs from a text book. They’re learning via a real-world, enquiry based activity. They’re using critical and creative thinking, problem-finding and solving, in order to figure out what’s happening in the pond, as tadpoles turn into frogs. In doing so they’re learning maths while collecting environment data, and using spatial reasoning when observing and recording changes in frogs.

The biggest thing for us is to have student agency involved.

Older students are working with the council to work out what it takes to build a sustainable city. They’ve spoken to town planners and rubbish collectors, and are examining what sustainable cities might look like in different environments – like underwater or on Mars.

“The biggest thing for us is to have student agency involved. We are working to have children leading their own learning really,” Clark says.

Like Blunt, Clark says it’s important to get school leaders to understand the importance of STEM and what they can do to improve STEM outcomes in their schools.

“I think the biggest challenge, and people come back and say this again and again, is to work out the structure behind what we do, and how it allows our teachers to work in this completely different way,” Clark says.

“Different schools can do it in different ways. What we do might not work for other schools. The paper gives us a few different ways of going about a STEM-based practice.

What Clark is getting at is the adaptability of the STEM Practices approach. It contains enough flexibility for schools to apply it to their own context. It might look very different at two different schools but the underlying pedagogy remains the same.

The type of learning carried out at Prospect North Primary School and Sunshine College are great examples of how STEM can be integrated across the curriculum in a sustainable way.

STEM education for all young Australians puts forward a compelling case for Australia to implement a new framework which focuses on STEM capabilities to improve student outcomes. Doing so will give school leaders more scope to incorporate STEM into day-to-day teaching.

Without this kind of integration, it’s unlikely the Australian education system will be able to address the growing need for STEM skills across the entire workforce. If STEM outcomes aren’t improved among today’s students, it will be Australia’s disadvantaged communities who will be most affected.

Author: Susannah Schoeffel

Susannah Schoeffel is Senior Project Manager for The Connection and works closely with STEM Learning Hub schools who are demonstrating educational best-practice in disadvantaged communities.

Read the executive summary of STEM education for all young Australians Read the full report, STEM education for all young Australians For more information on The Connection.Social Ventures Australia acknowledges the generous support of Samsung Electronics Australia, Technology Partner of The Connection and the STEM Learning Hub.