Building an evidence movement in Australian education

For 10 years, Evidence for Learning (E4L) has helped great practice become common practice. Here, we reflect on its contribution to Australian education and lessons for catalysing innovation.

- For nearly 10 years, Evidence for Learning (E4L) has helped great practice become common practice in schools and early childhood education by incubating a new national knowledge broker. Before E4L, research evidence was available for some, but not all.

- As the service moves on from SVA, we reflect on its contribution to Australian education and lessons for catalysing innovation in the social sector.

- Lessons learned included: even though it’s global, good evidence has to be local; lift the system by leveraging the capabilities of existing actors; and pilot with purpose and learn out loud.

Author: Matt Deeble, founding ceo of Evidence for Learning

Author: Danielle Toon, previously director, Evidence for Learning

Contributor: Patrick Flynn, previously director, Public Affairs

It is well-known that two major gaps exist in Australian education.

The first is a gap between ‘knowing’ (research knowledge) and ‘doing’ (change in practice) in school and early childhood education. The gap in the health care sector is 17 years;1 the gap in education is likely even longer.

The second is the achievement gap between children and young people from poorer backgrounds and their more advantaged peers. This gap is especially concerning as there is a strong relationship between success in education and participation and productivity in society.

Developments overseas suggested that one effective way to address these two problems at the same time is to improve the use of research evidence across the education system. This leads to better approaches being available for those children and young people who will benefit the most. SVA incubated Evidence for Learning (E4L) to see if that approach might work in Australia’s education system.

This article summarises what and how E4L contributed. It also provides insights about E4L’s innovation process giving greater detail about what and how E4L worked.

Educators with better access to better evidence will make better decisions

E4L’s premise is that when educators have better access and support to use quality knowledge, they are more likely to adopt effective teaching approaches (and retire less effective approaches). In turn, these changes increase learning gains.

To that end, E4L improves the quality, availability, and use of education evidence by collaborating with different actors, working as a ‘knowledge broker’ between them all. This includes collaborating with educators, researchers, policy makers, systems leaders, professional learning providers, philanthropists and the wider community.

Before E4L, research evidence was available for some, but not all

When E4L was created in 2015, the idea that leaders would demand evidence of impact of teaching approaches was quite novel. Some education researchers, most visibly Professor John Hattie from 2009 on, had popularised the ‘effect size’ statistical measure to compare learning gains.2 However, awareness of research evidence and engagement with the research were uneven in Australian schools and early learning settings.

Wealthier schools and large-scale early learning providers could afford research leads and data analysts but most others could not. Investment in education research at a system level was negligible compared to that of health and other sectors. But here was an opportunity to mainstream and scale an ‘education evidence’ system for everyone and by doing so ‘lift all boats’.

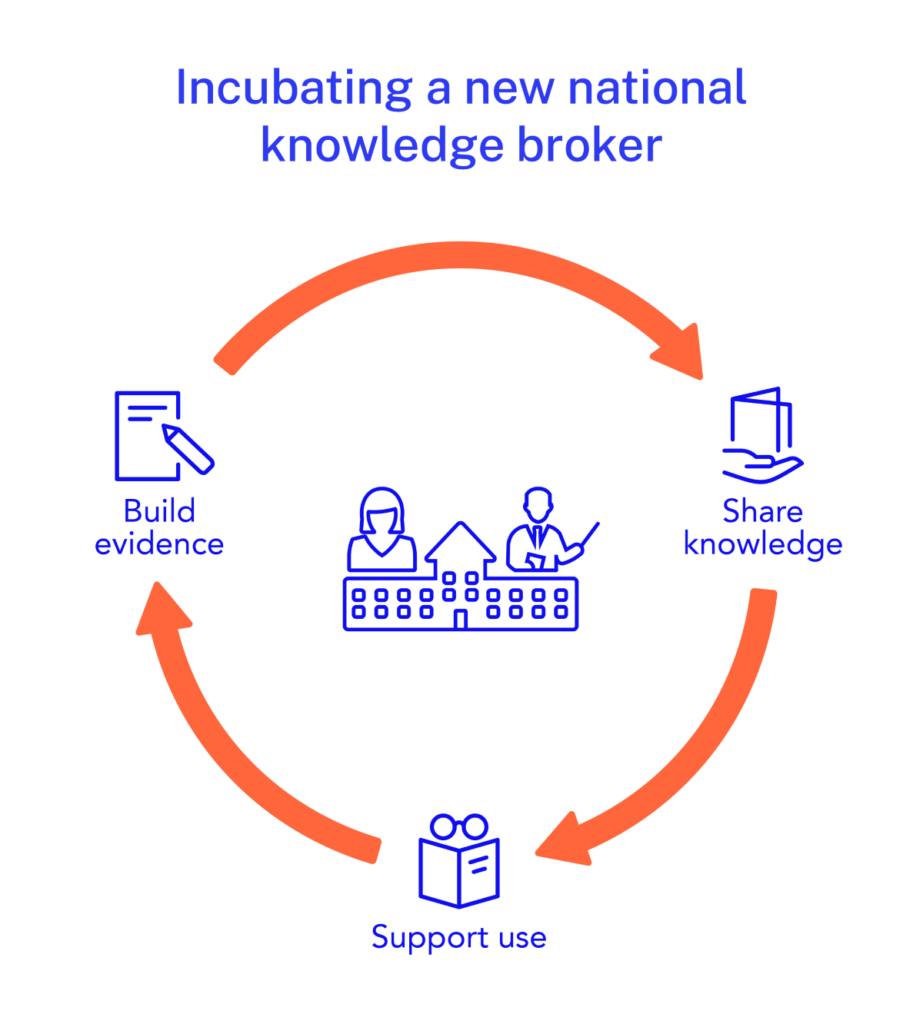

Incubating a new national knowledge broker

SVA seized on the opportunity to replicate developments from overseas by convening and then combining organisations and people with discrete and complementary talents from across education, research, policy and philanthropy. SVA secured a pilot agreement with the UK’s Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) to use its global resources that include accessible summaries of more than 30,000 high quality education research studies. SVA then partnered with the Commonwealth Bank and a series of visionary philanthropists to build and maintain a small but skilled team to create the new ’knowledge broker‘.

Learning from the EEF’s experience, E4L committed to ‘build’, ‘share’ and support the ‘use’ of evidence. E4L had many successes.

- Build evidence: Commissioned three randomised control trials, two pilot studies, four systematic reviews and two research investigations.

- Share knowledge: Published over 175 evidence-informed resources for educators, including the Teaching & Learning Toolkit, the Early Childhood Education Toolkit, Guidance Reports and ‘tailored’ Toolkits

- Support use: Materials had over 26,000 frequent users and nearly 190,000 downloads*. Partnered to deliver over 425 professional learning events to a total of over 16,000 educators.

*As of early 2024

Advocating for larger change

In parallel to modelling a national ‘knowledge broker’ for Australian education, SVA executed a multi-year advocacy agenda to put evidence use at the heart of Australian education reform. This included calling for the Australian Government to establish and fund an independent, national education evidence broker through submissions and presentations to national inquiries, participating in public forums and engaging in sector networks and with policy makers. This was instrumental in the creation of the Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO), which was established by the state, territory and federal governments in 2021. The creation of AERO fulfilled E4L’s endgame and reflected its success in advocating for accessible, quality evidence across the Australian education system.

Still free and open resources for all

In March 2024 E4L moved into its next phase, beyond SVA. E4L now operates as a stand-alone website at https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/ All of the evidence assets remain available to Australian educators and others free of charge.

Lessons learned for social sector innovation

At SVA’s Impact at Scale Summit in 2023, Matthew Taylor, CEO of the NHS Confederation in the UK, encouraged social sector innovators to “think like a system and act like an entrepreneur”.

This is a good description of how E4L pursued its goals over the last decade. It helps us frame the key lessons into three themes:

- Even though it’s global, good evidence has to be local

- Lift the system by leveraging and amplifying the capabilities of existing actors

- Pilot with purpose and learn out loud.

1. Even though it’s global, good evidence has to be local

Education evidence puts the lessons learned across thousands of schools and early learning settings into the hands of an educator as they make decisions about what to do in their classroom on any given day.

For a busy educator to use the available evidence, they must trust both its quality and its relevance. Left on the library shelf, this evidence has precisely zero impact.

For quality, E4L privileged research with methods that give higher confidence in its reliability across different settings. The research evidence was ‘global’ – it was drawn from studies from around the world based on transparent and systematic evidence standards with reliable benefit for classrooms anywhere.

Educators also need to see how the evidence is relevant to their context and to see the research they already know be represented.

Where this is done well, educators demand the evidence to help them and the system then supplies what they are asking for. This ‘pull’ for evidence is far more effective and durable than a system ‘push’.

E4L used various methods to make this global evidence ‘local’ for Australian educators.

a) Aligned global evidence with the local system frameworks used every day

E4L started with the global evidence and then added local references and expressions in all our evidence products. We ‘localised’ the global Teaching & Learning Toolkit (an online summary of the evidence on 34 approaches) in a number of ways:

- local lexicons of students, school leaders and year levels (instead of the jarring English expressions of pupils, head teacher and key stages)

- companion Australian studies alongside the global references

- tailored for each education system (e.g. Victorian Department of Education) referenced and aligned with the school improvement model those educators worked with and reported against.

This tailoring led to strong adoption and use – up to 22,000 visits a month.

“In my role, I spend a great deal of time collecting, reading and unpacking research around teaching practice and approaches with our teachers,” said Frances Roberts, former head of curriculum at Bounty Boulevard State School. “The [Teaching & Learning] Toolkit is neat, concise and easy to use. It will save me countless hours in the way it lights the path directly to the most relevant and reliable research.”

b) Enlisted local experts to improve the global evidence for our audiences

E4L’s Australian Guidance Reports were another example of a commitment to combining global evidence with local expertise to support Australian educators.

We used already summarised global recommendations in a process with Australian topic experts – both researchers and practitioners – to build better local expressions and include Australian illustrations and examples of relevant practice and activity. We have seen nearly 170,000 downloads and use of these localised resources.

c) Shared local evidence back to improve the global system

E4L also made sure Australian perspectives and agendas were linked into global education evidence development. We appointed Australian research organisations to our evaluator panel and ensured they had dedicated training and access to evaluation experts internationally. Our Australian team also ran global working groups on local evidence mobilisation bringing the local stories to life for global partners who might use them in their own contexts. In turn we learnt from their evidence mobilisation experiences in their countries and contexts.

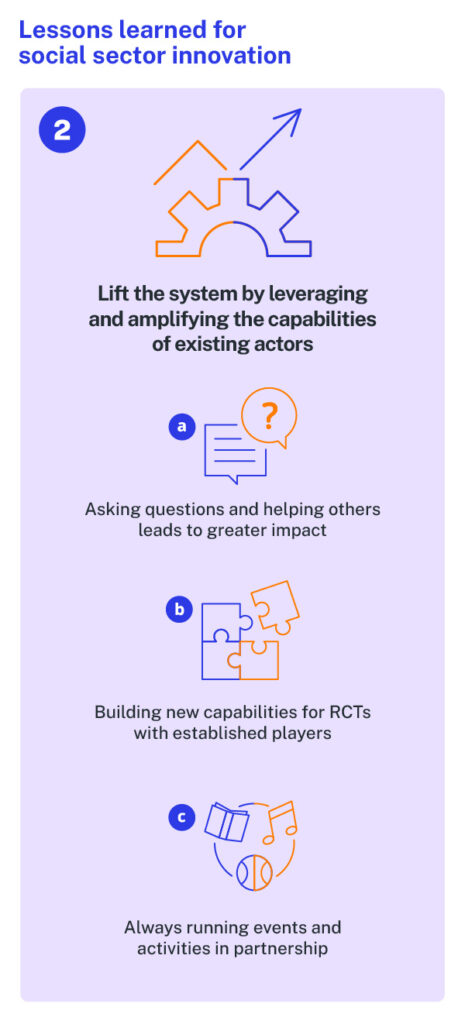

2. Lift the system by leveraging then amplifying the capabilities of existing actors

Our aim was to have a healthy system of evidence generation, synthesis and mobilisation that supports practicing educators. We knew that could not be achieved by just one organisation, either existing or new. From the beginning, E4L mapped all the stakeholders and players who influenced schools, early learning settings, leaders and educators.

These included departments of education, regulators, education researchers, teacher training institutions, unions, professional associations, training organisations, education program developers, publishers, media – broad and narrow, think tanks and policy bodies, and politicians and their advisers.

We listened, considered, partnered and learned how these stakeholders might help meet the healthy system aim.

a) Asking questions and helping others leads to greater impact

We asked questions like: what are their existing views on research evidence? What could improve their work and impact? What was stopping them using evidence better and what was needed for change?

We considered how E4L could cast the best light on those who already had important roles in the system and would therefore take the work further, faster than our small team ever could. This required a lot of time in meetings with leaders from across all the organisations. We listened carefully to their needs and concerns, formed genuinely collaborative, power-sharing partnerships, then adapted and changed approaches based on the new knowledge.3, 4

Emeritus Laureate Professor John Hattie and Chair of Evidence for Learning’s Schools Expert Reference Council recognised E4L’s contribution: “Evidence for Learning has played a vital role in the education system – collaborating with researchers, systems and practising educators to make research evidence on education more useful and more widely used.”

b) Building new capabilities for RCTs with established players

Part of our plan included showing how Australia could run high quality research called randomised controlled trials (RCT) on promising programs in education settings.

E4L used partnerships and collaborations to set these up. Firstly, we asked education departments to suggest programs they invested in or wanted better evidence on and we asked them to co-fund the work with us. Once completed, E4L celebrated and promoted the program developers who agreed to hold themselves to a new, higher standard of evidence.

We deliberately commissioned and funded existing evaluation organisations in the sector to conduct the trials – so that E4L was building up their expertise and capability.

This model produced Australia’s largest RCT involving 158 schools with more than 7,000 students in South Australia. This improved the national discussion about high-quality evidence referenced in various education and finance minister addresses.5

Laureate Professor Jennifer Gore, Director of Teachers and Teaching Research Centre at Newcastle University, affirms: “SVA’s support for experimental studies in education paved the way for a new eco-system of high-quality evidence production and built capacity across the sector for such work in Australia. I can attest to E4L’s important national leadership of this approach.”

c) Always running events and activities in partnership

Every roundtable, conference, workshop or professional learning session E4L ran was in partnership with an existing actor in the system. This both helped our credibility but also added the evidence agenda to theirs. We ran, for example, a large, multi-year research program on evidence mobilisation in schools in partnership with the Victorian and New South Wales education departments.6

John Cleary, Senior Director, Education Improvement, Northern Territory Department of Education acknowledges the relationship his department had: “Since establishing our evidence partnership back in 2018, [E4L has been] a significant evidence partner for the Department of Education Northern Territory. E4L partners, past and present, played an important role in the improvement journey in the NT.”

3. Pilot with purpose and learn out loud

E4L began with a general ambition for how we wanted the Australian education system to improve with evidence, informed by the experience of our UK partner, the EEF.

We knew the journey would be different to theirs for many reasons. E4L didn’t have anything like the funding size of the EEF. The structure, funding and management of schools and early learning settings is very different with Australia’s federation of states and territories and three education sectors (of government, Catholic and independent schools).

We also knew E4L had to be ambitious but efficient in our pilot work and advocacy and we needed to bring partners along for the journey to achieve sustained impact on the education system at scale. A good way to do this was to spend philanthropic money on research answering questions of interest to education authorities.

a) Philanthropic risk-taking helps systems determine whether to invest for scale

E4L was fortunate to have substantial, strategic, multi-year philanthropic support from the Commonwealth Bank and other philanthropic partners. This signalled to education departments, politicians and partners that E4L could explore and take financial risks with projects and ideas so that they didn’t have to. We made clear everything E4L was doing in pilot was to determine if it was worth others taking these ideas to scale.

b) A public commitment to open reporting and sharing learnings builds trust

E4L had an explicit and ongoing commitment to share all results of evaluations, investigations and literature reviews in public, open access on our website and other forms of ‘learning out loud’. We wrote public papers to the sector and submissions to inquiries and panels including to the Productivity Commission inquiry into education evidence in 2016 and to the Gonski 2.0 panel in 2018. We also presented more sensitive learnings in appropriate forums with system leaders that engendered trust and access to opportunities that would not normally be afforded to a start-up organisation.

c) Working with purpose enrols others in the system change

E4L worked hard to make sure the idea was supported by all political parties across the spectrum. The team spent time in Canberra and elsewhere to entrench the idea that evidence is beyond politics and both sides should support more and better evidence leading to better outcomes.

In this we were very successful. This reform was championed by both Labor and coalition government education ministers which saw federal bipartisan commitment to the establishment of a national education evidence institute, now known as the Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO).

In February 2018, Labor pledged its support for an independent education institute.7

In May 2018, Senator Simon Birmingham MP, then federal minister of education in the Coalition government said of the envisaged evidence institute: “We need to get this new institution right… to ensure that evidence informs practice and that it all flows through into the classroom setting.”8

Importantly, thanks to the advocacy of many, establishing AERO was maintained as a national priority throughout the Covid pandemic.

By June 2020, the Coalition had agreed to invest $25 million towards the $50 million national education evidence institute with the states and territories funding the rest.9 This was achieved even when many other reforms outlined in the National Schools Reform Agreement (the blueprint agreed to by the education ministers across the country) stalled or were set aside.

d) Piloting and partnering helped achieve the ‘end game’

Creating a national evidence body was the end game we set for E4L.10 In AERO, there is now a national body with an independent board and the potential to add value to all parts of the education system.

AERO is jointly owned and funded by the nine state, territory and federal governments. It is one of four national education agencies and now plays an important role in Australia’s education system.

As part of concluding this phase, E4L offered a view of ‘what next’ by commissioning a paper on the future of Australia’s education evidence system.12

Conclusion – is it making a difference?

So where is Australia after nearly 10 years of building, sharing and using evidence in education? There are improvements in our national education conversation. ‘What’s the evidence for that?’ is a challenge as likely to be heard from a teacher in staffroom chat as an education bureaucrat these days.

There are encouraging signs that policy makers and practitioners are better able to distinguish between different kinds of evidence and their appropriate use in decision-making. There is bi-partisan commitment to an evidenced-based approach for investment decisions and Australian governments (federal, state and territory) have invested in a national body to support and advance that agenda. And there is a global education evidence movement that has substantial momentum that Australia has been a leading voice in.

However, evidence use is not an end in itself and most national11 or collective measures for Australian school or system improvement are flatlining or declining for both achievement and equity. So if Australia is using evidence better, it’s not making enough of a difference, or not yet anyway. It’s a long-term game. We started this story looking at the UK’s experience with investment in evidence systems. England’s overall improvement since 2009 has been attributed, in part, to the quality of its evidence commitment, so perhaps Australia’s returns are still to come.13

Realising the benefits of the investment to date will require building demand from the teaching profession. A movement has started and the institutions are in place but it’s the support given to educators and leaders over the next five years which will really determine the success.

As the next phase of evidence-informed practice and policy in Australia plays out, it is on a stronger footing. Educators and their supporters are more engaged and empowered thanks to SVA’s commitment and leadership in establishing and supporting E4L. As all good intermediaries do, SVA through E4L lifted other organisations up and joined them together to make the meaningful difference.

Social Ventures Australia wishes to thank the philanthropic funders who supported the establishment and operation of E4L over the years, including BHP Foundation (2022−2023 funder), Ian Potter Foundation (2022−2023 funder for early childhood education), Commonwealth Bank of Australia (founding funder), The Bryan Foundation (founding funder for early childhood education) and other funders who supported collaborative projects.

1 Morris, Z. S., Wooding, S., & Grant, J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 510–520, December 2011

2 Effect sizes are quantitative measures of the impact of different approaches on learning. They describe the size of the difference between two groups in a standard and comparable way. For more information on effect sizes and months’ impact as used by Evidence for Learning, see here.

3 Examples of E4L’s relationships, E4L website, accessed August 2024

4 Examples of E4L’s collaborative projects, E4L website, accessed August 2024

5 Senator Simon Birmingham, Address to speech pathology Australia conference, Adelaide, Senator Birmingham website, May 2018, accessed 15 May 2024

6 For more examples of E4L collaborative projects and professional learning partnerships, see the E4L website.

7 Labor pledges $280m research institute to ‘take politics out of the classroom’, The Guardian, Feb 2018, accessed August 2024

8 Senator Simon Birmingham, Address to speech pathology Australia conference, Adelaide, Senator Birmingham website, May 2018, accessed 15 May 2024

9 National evidence institute gets $50m in funding, The Educator Online, June 2020, accessed 15 May 2024

10 Alice Gugelev & Andrew Stern, ‘What’s Your Endgame?’.Stanford Social Innovation Review, winter 2015

11 See for example, PISA 2022: Australian student performance stabilises while OECD average falls, ACER website, December 2023, accessed August 2024

12 Dr Tracey Burns, The evolution of evidence-informed policy and practice: an international perspective, E4L website, September 2023

13 While England’s 2022 PISA results were impacted by Covid-19, they have been steadily improving in reading and mathematics since 2009. See for example England among highest performing western countries in education, UK Department of Educaton website, December 2023, accessed August 2024